The Author of Geek Love Left Behind an Extensive Body of Unpublished Work

Katherine Dunn, author of Geek Love

When an artist dies, everything they’ve touched becomes precious. The fountain is cut off, so we dive deep, groping for more of whatever it is we loved in their work. This has been the case with the archive of Katherine Dunn, the beloved Portland author who died in 2016. In 1989, at age 43, she published Geek Love. Inspired by the bioengineered flowers of Washington Park’s International Rose Test Garden, Dunn wrote a surrealist tale of genetically modified circus freaks, an ode to misfits. The book would win the hearts of celebrated outsiders spanning Kurt Cobain and Courtney Love to Tim Burton—who to this day owns the novel’s film rights. To most people, Geek Love was the extent of Dunn’s fiction. But an accelerating trickle of posthumously published fiction is unearthing a rich, never-before-seen body of work.

Before she died, Dunn bequeathed her papers, 47 legal file storage boxes, to the archives of Lewis & Clark College in Southwest Portland. One box holds a postcard from Stephen King dated 1982: “Thanks for the Cujo review,” he wrote, referencing Dunn’s write-up in Willamette Week. (She wrote for the alt-weekly through the ’80s.) She was in touch with the local literary scene, too. Ursula K. Le Guin wrote two years after Geek Love was published and asked, superstitiously, about a next “b**k.” A 1996 letter from Chuck Palahniuk, addressed to the Nob Hill house where Dunn lived for most of her adult life, thanks her for the blurb on his upcoming book Fight Club’s cover.

Most of the archive is publicly accessible, though some materials are held back for potential future publication.

A chalky blue linoleum folder with a coffee ring on the inside holds numerous typewritten drafts of a short story titled “The Education of Mrs. R.” and three tattered copies of it printed in the Clinton St. Quarterly. It shares real estate on the brittle, yellowed newsprint with an ad for John Sayles’s 1979 movie Return of the Secaucus 7.

Flash forward to 2022 and that same story, the tale of a rural housewife (in what feels like Oregon, though it isn’t specified) left to dispatch some 50 unruly roosters, is in the pages of the Paris Review. Another short story culled from Dunn’s papers, “The Resident Poet,” a study of power dynamics that outlines a student’s joyless affair with a professor, was published in the New Yorker in 2020. Coupled with that story was an interview with Naomi Huffman, a New York–based editor who’s become the quasi-executor of Dunn’s unpublished works. “The story will be included in a collection of short fiction … following the publication of her lost novel Toad,” Huffman told the New Yorker. COVID scrambled the dates a bit, but November 2022 brought the “lost” novel to booksellers—though Huffman would later reject the “lost” label. The short story collection is yet to be released.

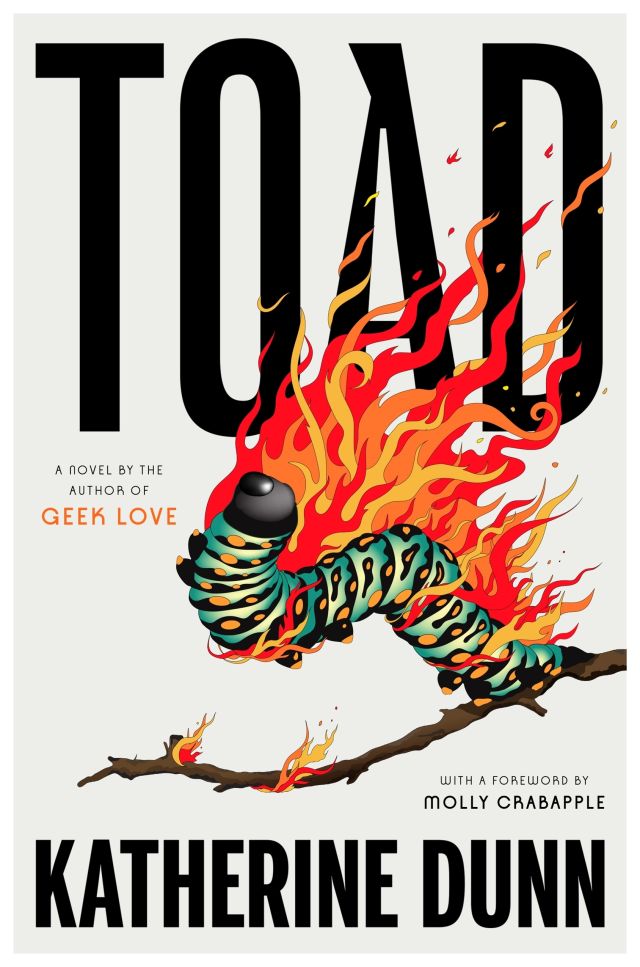

Toad, in fact, was anything but lost. Dunn published her first two novels, Attic (1970) and Truck (1971), before her 26th birthday. But Toad, her third manuscript, turned in a few years later, was rejected. Revised, then promptly rejected again. Then shopped around for nearly a decade with no success. Eventually, Dunn moved on, leaned into her reporting career, and began slowly working on a new project, Geek Love, in her spare time.

Toad was published in November 2022, nearly 50 years after it was written.

Dunn’s first two novels were poorly reviewed by critics, which could explain Toad’s rejection. But Huffman argues in Toad’s editor’s note that the novel was ignored by an oppressive system; literature of the time, she writes, celebrated overwhelmingly cis male narratives (“a sliver of the spectrum of human experience”).

Toad’s pages brim with the devastating and poignant observations Dunn’s work has become known for. It is an unsparing and uncomfortably emotional account of a version of Dunn’s days as a sometimes-student at Reed College, told through an alter ego named Sally. (“The Resident Poet” shares a similar setting and protagonist, also named Sally.) In middle age, Sally reflects on her past, narrating, as it were, to her goldfish and the toad lurking in her garden: both alien, solitary, and cold-blooded like her.

Through her now four novels and various short stories, Dunn fleshed out the performance of daily life with unparalleled grace and calculated immediacy in her prose. Her work was ahead of its time in unpacking the nuance of the quotidian, asking what meditating on taken-for-granted banalities—and the unspeakable realities therein—can teach us about ourselves and the world, our systems and relationships.

After publishing Geek Love, Dunn went back to working as a journalist. As a reporter, she was best known for covering boxing with a feminist slant, but she also published cultural criticism in Playboy, Vogue, Rolling Stone, Esquire, and the New York Times, among others. Notes and drafts of her articles, along with copies of the now-vintage magazines and newspapers are spread throughout the archive. Several folders are devoted to research on Courtney Love’s life and career—a deep dive that culminated in a 1995 essay for Vogue. In it, she called Love “the current icon of female bad behavior” and articulates more explicitly a common sentiment of her fiction: celebrating women “recognizing and embracing the fact that they possess the entire human spectrum of emotion and behavior.”

Outside of her fiction, Dunn was a prolific boxing reporter.

Dunn notoriously worked for decades on a follow-up to Geek Love. Cut Man was to be a novel dealing with boxing and serial killers, but in the years between turning in the book’s proposal and Dunn’s death, she was unable to tie the plot together. Drafts of Cut Man are under restricted access in the archive, however, so something could be made of them in the future.

Toad’s manuscript was made available to the public after the book was published last year. It’s about three inches of stacked paper of varying weights and sizes—faded typewritten text, rusted at the corners. The last page, hand-numbered 307, flirts with companionship: “We could play out cartoon tableaux, the cat and the fish and me. I don’t know if I’m ready for a warm blooded creature yet. Would a cat eat a toad?”

Another folder is packed with research and drafts of an article Smithsonian Magazine commissioned about Portland in 2010. “Portland was the town I ran away to,” she writes. She ran all the way from Tigard, into what the farm folk she had come to know in the ’60s burbs referred to as “a paved jungle of noise, danger and depravity.” This was the draw. And it’s this outsize, rough-edged, screwball version of the city and its surroundings that serve as the backdrop to her fiction—what we’ve seen of it, at least.