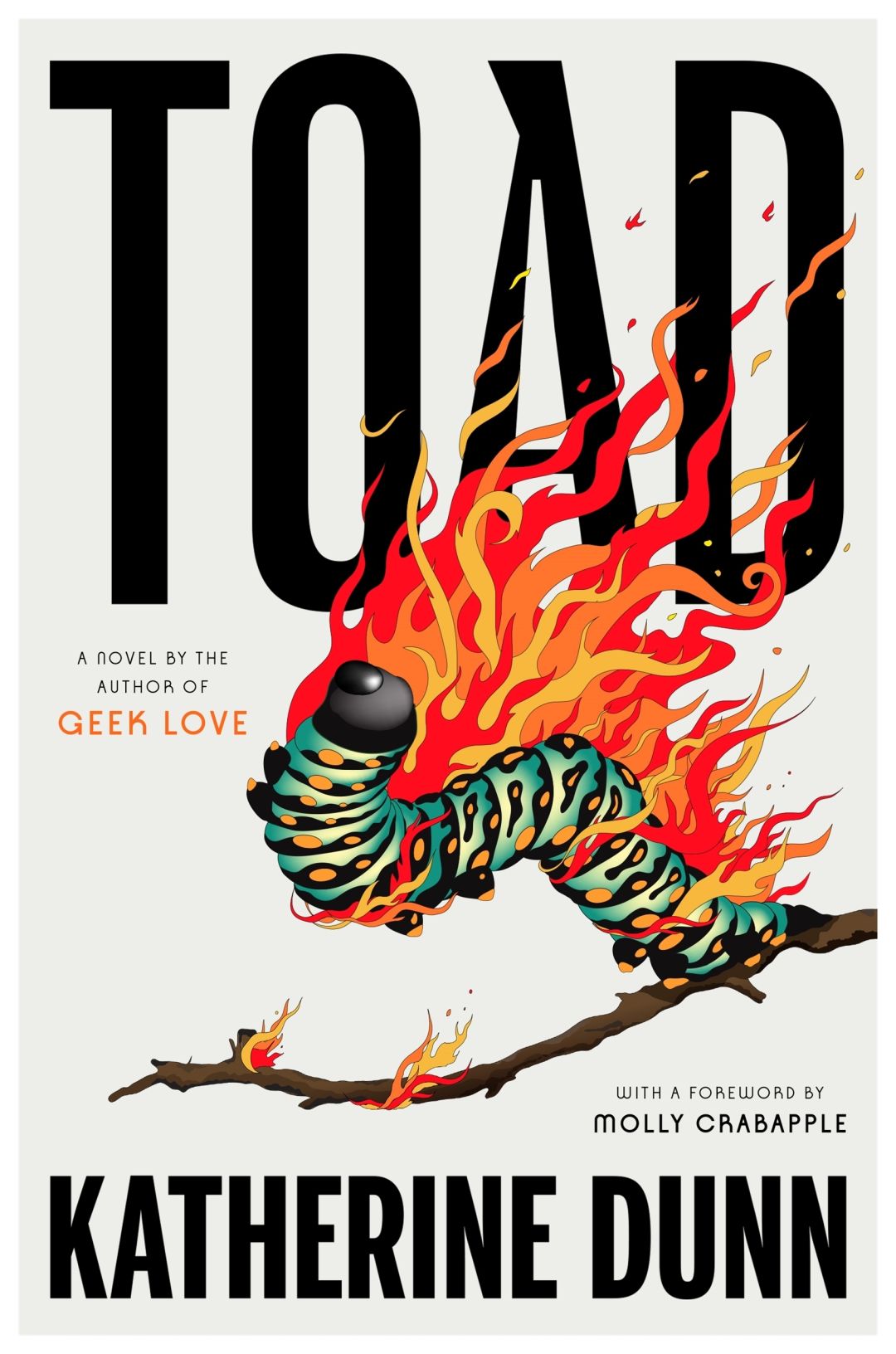

Katherine Dunn’s Posthumously Published ‘Toad’ Cuts Deep

Image: Farrar, Strauss and Grioux

Katherine Dunn, Reed College dropout, beloved Portland novelist, misfit queen to all, and boxing reporter for everywhere from Willamette Week to the New York Times, has a new book out. Which may come as a surprise, given that she died six years ago.

Fifty years have passed since Dunn wrote a novel about her days at Reed, told through the gray, depressive gaze of an alter ego, Sally Gunnar. But it wasn’t until November 1, 2022, that Toad was published, after spending the past half century as a loose, un-chaptered manuscript in the archives of Lewis & Clark College.

Dunn’s first two novels were released in quick succession, Attic in 1970 and Truck in 1971, both to poor reviews. Toad, her third manuscript, produced shortly after, was rejected. Many, including Naomi Huffman, Toad’s eventual publisher, believe the novel was ahead of its time—too progressive for the male narrative-centered market of the ’70s. For the 18 years that followed, Dunn’s fictional output was saved for nights and weekends, published in local independent journals, if at all. She worked most notably as a boxing reporter, but also as a waitress, a bartender, a radio host at Portland’s KBOO.

In 1989, Geek Love launched to the top of best seller lists, was a National Book Award finalist, and won the hearts of outsiders of every size and shape. It follows the children of Al and Crystal Lil, a carnival couple who intentionally breed their ilk to follow in the family business, manifesting birth irregularities like flippers and hunchbacks by ingesting arsenic and radioisotopes.

That book became the face of Katherine Dunn. The eccentric novel is, to many, the late author’s lone—but glowing—contribution to literature. However, Dunn’s archive (apparently) runs deep. A short story written in the ’70s, “The Education of Mrs. R.,” was published in the latest Paris Review; “The Resident Poet,” another culled from Dunn’s papers, with a similar protagonist to Toad’s named Sally, was published in the New Yorker in 2020. Huffman is also working to publish a collection of the late author’s short stories with publisher Farrar, Straus and Giroux that’s been delayed by COVID.

Image: Farrar, Strauss and Grioux

In Toad, Sally fantasizes about turning her attic room into a literary salon; intelligent kids who say words aloud she had only read in books would fill her squalor with intellectual light, sitting on her peach-colored velvet chaise lounge that “looks like it eats people.” Sally’s vision of herself is less romantic. She abhors the “curdled flaccidity of [her] flesh … the bludgeoned untidiness of [her] face.” She jabs at herself with sublime depth, while also delighting in her own wit and self-described “leonine ferocity.” The tableau of her holding court as an ersatz Truman Capote never materializes. Instead, Sally tells the story of her entire life, both as a twenty-something Portlander in the ’60s, and from the perspective of her older self (it’s unclear how much older, but decades have passed since her college years).

The polarity between the two voices speaks to the painful anxiety of asking, what happens if you never figure out this whole life thing? “People between the onset of puberty and 30 do not exist without people looking at them,” Sally reflects on her previous self. The world is our foil, baby! In the future, she describes her life of reading grocery-store paperbacks and subsisting on welfare—a life she performs for her goldfish and the toad in the garden—as a “child’s dream of being grown-up.”

Toad has the commanding prose of a heavyweight boxer, but not the genuine sparkle of Dunn’s classic novel Geek Love. Though beautifully rendered, the picture Toad paints is of ugly realism, counter to Geek Love’s surreal beauty; even flowers fall victim to Sally’s gray gaze. A tulip, plucked from the garden and held in water decays, “sluttish, drunken, allowing the musty purple core to protrude.” But extremes like this are contrasted with the charming rhythm of lines like “the sun was just getting fancy across the valley.”

The plot is frenetic, nonlinear, punctuated by discrete climaxes—and far from boring. Archetypes of private school kids fill out the cast: Sam, a garden-variety narcissist, speaks in monologues and mansplains his way through the world. Sally loves him; she compares him to a fly, but a polite and hilarious fly. Sam always stops to help, Sally says—hitchhikers, crying children, drunks in alleys—not out of compassion “but curiosity, and a lust for the something interesting that can be milked from every brush of another person.”

The book comes in neatly packaged vignettes as chapters that unfailingly name themselves—an organizing edit carried out after Dunn’s death. “Some of us despise our own youth with a vague and bitter nostalgia and fixate on our worst phrases and acts with miserable clarity,” begins the chapter titled “The Scarred Old Toad,” and serves as a decent synopsis of the plot. Another begins with a five-page preamble worshiping Sally’s favorite chocolate, the Volcano Bar, and proceeds to describe her 40-day "fast" (a diet) in which she savored only one Volcano Bar daily.

Somehow, not only are passages like this palatable, they’re page-turning, simultaneously growing Sally’s outré portrait and setting you up to see more of yourself in her than you might care to admit. At times, it’s a struggle to parse reality from hyperbole, like Sam’s “pillowcase stuffed with molded underwear” and his diet of rotted horse meat, scrapped of its green goo before being burned in a cast iron.

Huffman, who has become the quasi executor of Dunn’s archive with the permission of Dunn’s surviving son, Eli Dapolonia, has argued repeatedly that Toad, and more broadly, the large chunk of Dunn’s fiction she’s currently working to publish, was not “lost,” but ignored by an oppressive system. In the editor’s note, she writes: “I’ve come to consider ‘lost’ a sinister fiction that elides the cascading failures of an industry that for centuries has heralded the work of white cis men and erected a canon that celebrates only a sliver of the spectrum of human experience.”

The fact that Dunn herself was a woman is part of it, but it’s the stories she chose to tell that alienated her from the mainstream. Toad conjures the unwavering self-loathing narcissism that runs through most, but is admitted to by only a few. At the time, a woman’s life was not allowed to elucidate the ugliness of the lived experience. And Toad, unlike Geek Love, is not masked by a surreal world: it’s set in Portland in the ’60s (you could rent a room for $20 per month, and there still weren’t many bagels around).

Sally’s experience is by no means standard, but emotionally, it’s approachable. Her sometimes extraordinary circumstances always land quickly, as life does, on the question “What are you going to do now?” In the end, Toad is a harrowing portrait of an unexceptional life, filled with delusions of grandeur, and the sobering reality of what happens when you’re waiting for the world to happen to you.