Thoroughly Modern Surrealism with a Nod to Tolkien at Chefas Projects

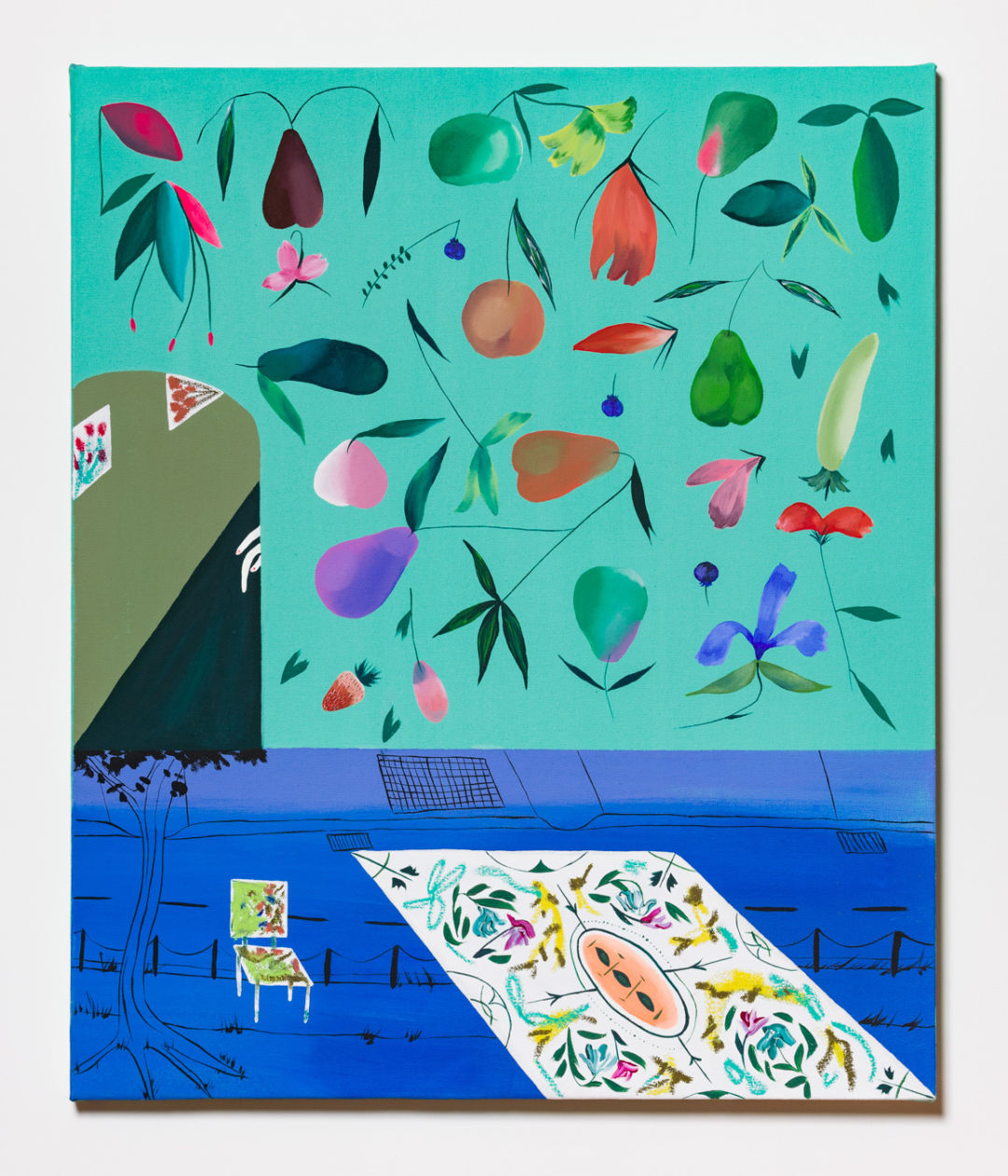

Laura Burke's Grin

Toward the end of October last year, Laura Burke, a Portland-raised artist now based in Brooklyn, New York, posted to Instagram a photo of a painting that would later be titled Grin. Fruit and flowers, a plate decorated with an arrow-wielding cherub, and various other motifs filched from historical still lifes were arranged into something akin to a smile; a swooping candelabra drew the eponymous smirk.

“I’ve been painting for four months now and it has generally been painless and I’ve only wanted to quit a few times,” reads the caption. Last Friday, eight months into her painting career, the Southeast Portland gallery Chefas Projects filled with Burke’s canvases. It’s not that she is an overnight savant—Burke has been a reputable artist for years—but the comical speed at which she’s adopted the medium is as cheeky and curious as the wit behind her pictures.

Laura Burke's solo show Bright Blue His Jacket Is, and His Boots Are Yellow at Chefas Projects

Repurposing canonical images isn’t new for Burke either, but the fresh medium marks a breakthrough in her work.

Her last Portland show, Inside Out, a series of colored pencil and oil pastel drawings collected last February at what was then called Stephanie Chefas Gallery, magnified “banal moments to make them extraordinary.”

Over the past five years or so, her work has grown from sparse and subdued colored pencil drawings on paper to richly saturated drawings mixing in oil pastels, and finally to this latest series of acrylic-painted canvases.

The current show, Bright Blue His Jacket Is, and His Boots Are Yellow, on through March 18, is made up of both mixed-media drawings and the new acrylic paintings, as well as a few combining the two. And while there is a clear visual jump between the paintings and drawings, they present as a cohesive body. They’re clearly created by the same person with the same purposefully off-kilter reality front of mind.

This show takes a turn towards magical themes. With a nod to J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Fellowship of the Ring (the show’s title is a quote from the character Tom Bombadil) the works, Burke writes in the artist’s statement, reach for a vague familiarity: “Nothing overtly magical is taking place, but [these objects] aren’t at home in this reality either.”

Recontextualizing the familiar immediately creates an uncanny, surrealist feel. These drawings and paintings, however, come off more inviting than unsettling. Though that’s also the trick of the uncanny: intrigue probing at the threshold of discomfort. Burke has said in the past that her goal is to invite viewers to draw their own narrative from the objects collected in her works. In effect, some of the distance between the canvas and the viewer is removed, as many surrealists before her have done, creating a more immersive than voyeuristic experience.

Laura Burke's Behind a Wall and Through a Window

Casually, the artist’s statement continues: “They’re household objects and bits of nature that I’ve arranged despite the laws of perspective to invoke another world.” Despite the laws of perspective—it’s in these touches that the sense of something being a bit off creeps in. Again, nothing is overtly sinister, but there is a sterility to details like tidy edged tiles flecked with ants and grass juxtaposed behind a ghostly curtain in the painting Behind a Wall and Through a Window. In the foreground, an apple springs from a horsehair-thin branch, still attached to its tree but eaten down to the core: apple turned classic surrealist image of something dead but threatening animation, still growing but already eaten.

Being an apple, if we’re to take it just as an apple, the sentiment lands innocuously enough. It’s a bit creepy, but lighthearted. Another interpretation: apple as memento mori.

Laura Burke's solo show Bright Blue His Jacket Is, and His Boots Are Yellow at Chefas Projects

This tension is a delicate balance. In the most effective pieces in this show, it’s thrilling, and it grips most thoroughly in Burke’s new paintings. Flowers are more fragile than their real-life counterparts. A monarch butterfly trapped under a glass—next to a toad and sitting on top of a porous brick wall—dares you to spin your own yarn. Who trapped it? Why? How weird does this story get?

Compositions in this show vary dramatically. Burke’s paper drawings, of equal scale and substance to the paintings, show a more diverse range in texture and approach. Smudged pastel sits next to crude-sketched grainy outlines of fruit and ornate, penciled recreations of angelic figures on pottery.

It’s as though the frenzy of these busier works distracts from their potentially unsettling groupings. Objects that don’t necessarily “go together” and mismatched points of view lock into a collage-like relationship. Whereas, when there’s enough air left to process the awkward juxtapositions, the disquieting sentiment is forced upon you.

Laura Burke's Swan in the Hallway

Swan in the Hallway doesn’t feature any swans, but its wash of bright blues and shades of turquoise hold plenty of the emotions often symbolically attributed to swans: light, purity, intuition, grace. Swans also signal peace and tranquility, but always with a whisper of something suspect lurking. But so do cats—the proverbial swan here, with its hind legs and pink toe beans peeking through the hallway in its own dimension. There’s also a botanical spread, a line drawing of a landscape, and what reads as a version of one of Burke’s other canvases, self-referentially hinting at infinite multiplication—all of which are rendered in their own opposing perspectives.

There is such a palpable playfulness to Burke’s work, which, depending on how you receive it, can either add to the eerie twists, or efface the potentially serious subtext. Remember, it’s your narrative to write.

Laura Burke's Most Fun You Can Have with Your Clothes On

Most Fun You Can Have with Your Clothes On combines both avenues of Burke’s work, mixing acrylic paint and pastels, delicate fruit, translucent glassware, and gossamer curtains. It’s a busy but balanced composition with multiple vignettes in multiple perspectives. Maximalist, yet everything is refined and dainty when separated to its component parts. Cherubs dance, wine spills, a candle flickers, and vines spring from a faintly rendered vase. It’s unstable behind the blissful façade presented in the storied paintings its motifs borrow from.

What’s going on? You tell me—so says Burke.