Pace Taylor’s Work Is About Slowing Down, But They’re Climbing the Art World Quickly

Top image: Pace Taylor's Table for One, courtesy Pace Taylor and La Loma Projects

It’s early October 2022. Pace Taylor, 30, is explaining the makeup of their upcoming show the next month at the Los Angeles gallery La Loma Projects. They say they’re using “Hitchcock as shorthand.” Studies of Judy/Madeleine (Kim Novak) from the director’s 1958 noir Vertigo cover the walls of Taylor’s third-floor walkup studio, a small square room in a reclaimed grain mill that looks out over the Willamette.

The film, Taylor says, is about loss of identity, imposing desirability on others as well as on ourselves—changing ourselves for others. Romantic relationships are part of it, but, as adapted to Taylor’s works, the narrative is more about drawing space for different identities in the maelstrom.

Taylor identifies as neuroqueer, a term often adopted for its accommodating definition, but which speaks above all to the abandoning of neuro- and heteronormativity. Being autistic and transgender, for Taylor, are inextricable: “I see these things as very linked. I can’t, like, take one apart from the other.”

Pace Taylor at their North Portland studio

Image: courtesy Ryan Warner

Taylor is wearing a beanie, Blundstone boots, and round glasses; they’re covered in the dust of soft pastels and have left handprints on the hips of their carpenter’s pants.

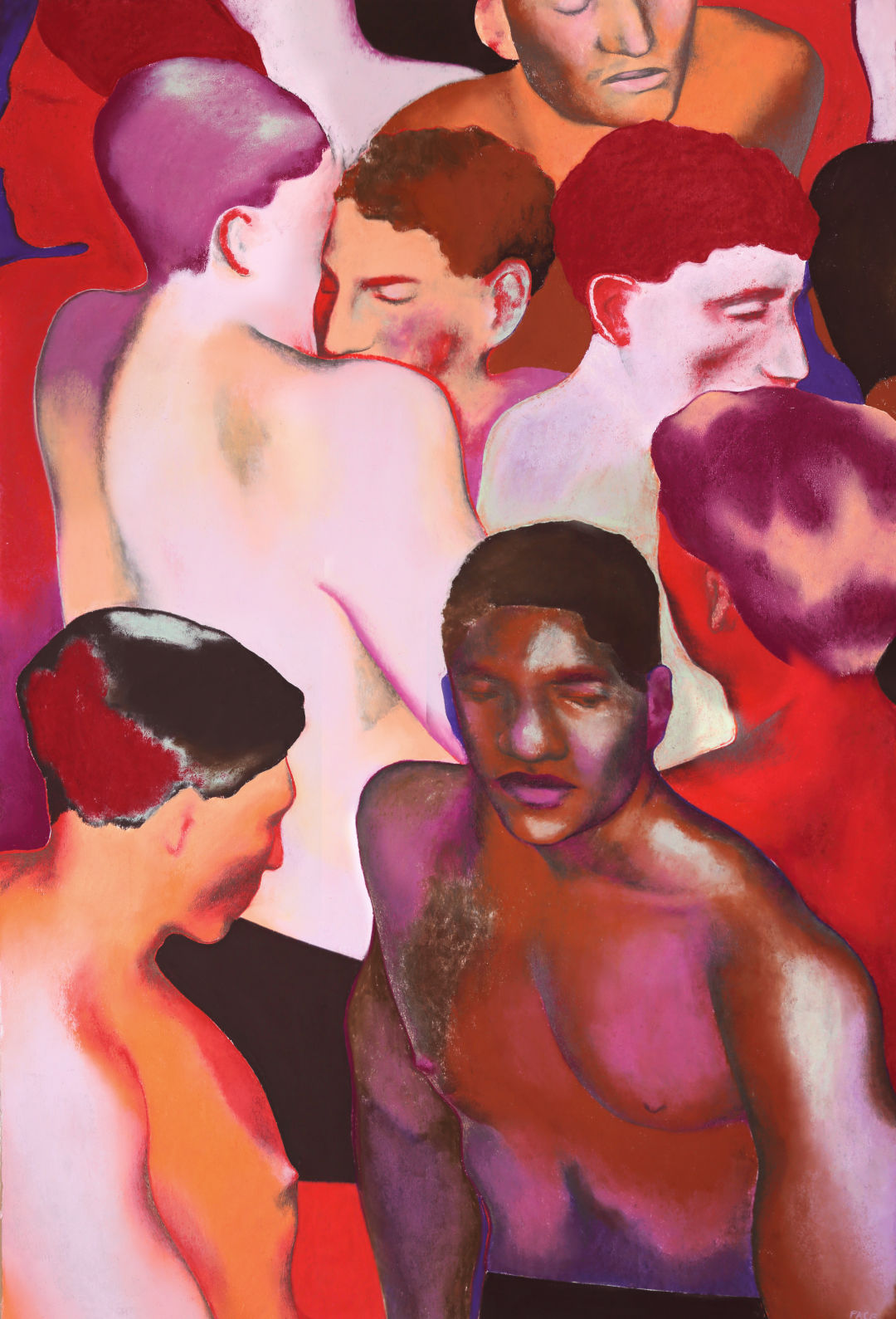

The show is mostly finished, save for some of the artist’s now-signature graphite detail work in the face of one figure and the hands of another. The pictures function as a storyboard of a very different movie from Hitchcock’s. But, standing in the room surrounded by the large portraits, it’s hard not to feel the constricting emotions the film conjures.

A series of close-cropped studies referencing Vertigo’s opening credits are tacked to a cork board in the corner. Hitchcock mostly focuses on a single eye, but Taylor’s postcard-size snapshots, all a deep, burnt red thoroughly saturated with the oil-slicked chalkiness of pastels, appropriate the concept to a caressing hand, the nape of an exalted neck, another hand coddling a match from the wind. They’re supposed to capture the feeling of an oncoming panic attack, Taylor says.

The New Yorker recently commissioned Taylor to draw a portrait of Elliot Page to accompany a profile outlining the actor’s gender transition both on- and off-screen during filming of the Netflix show The Umbrella Academy. Taylor also drew their own picture of Oscar Wilde’s titular protagonist Dorian Gray to garnish the cover of Signet Classics’ latest reissue of the philosophical novel. In the fine art world, collectors can’t get enough, and waitlists run on for pages.

Taylor’s parents, Beth and Jerry, who are big supporters of their kid’s career, paint a picture of a suburban childhood just south of Portland in Tigard. They say Pace grew up playing soccer and had a healthy media diet of Veronica Mars and Supernatural, James Stewart, Humphrey Bogart, and “all the Disney movies, of course,” Beth adds. Fine art didn’t come until high school, but in childhood Taylor’s observational skills stood out.

They studied digital arts at the University of Oregon, graduating in 2015, but felt uninspired by the potential career opportunities. They carried on a nights-and-weekends art practice while holding jobs at a florist’s, a plant nursery, a grocery store, and an ice cream stand at a farmers market (“a fun constellation of customer service jobs”). While between day jobs in 2019, Taylor says, “I gave myself two months to figure out if I wanted to do the art thing or try to find another job.”

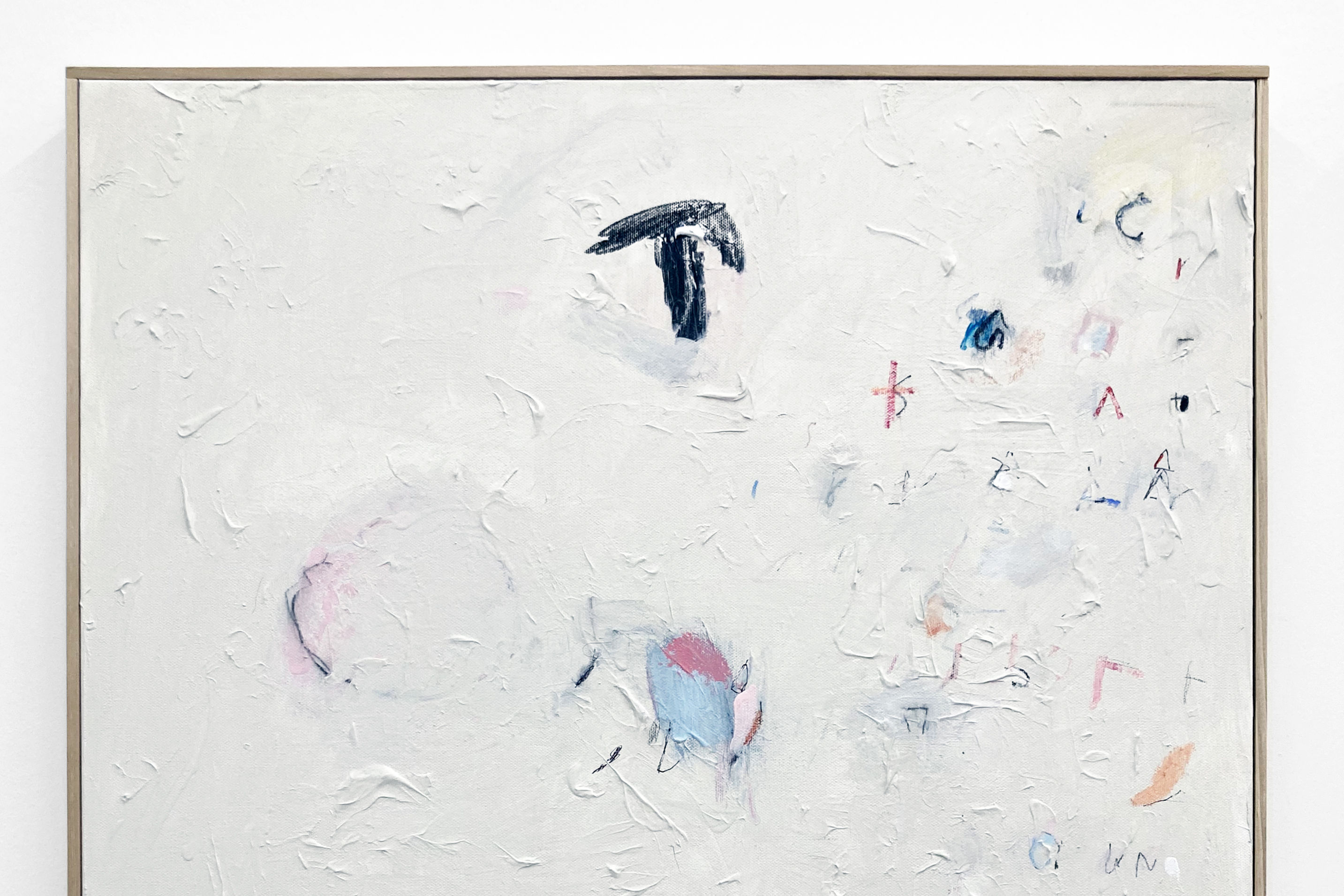

Judy (Slow Disco), People Needing Other People, and Kissing in the Dark (Make Me Over) at La Loma Projects in LA

Their process is to craft composite scenes from found photos, perhaps screen grabs from movies, and emotions gathered by watching other people interact. The pictures are not of someone per se, but of a feeling. The figures are anonymous (with the exception of, say, Hitchcock’s characters) and usually aren’t created with a gender in mind. “The person doesn’t totally matter to me, it’s more about the emotion that they’re carrying,” Taylor says.

After seeing one of Taylor’s drawings as part of a group show in another local gallery, May Barruel, owner and curator of the Southeast Portland gallery Nationale, quickly became enamored with what she calls “the quiet stories of everyday intimacy” that Taylor’s work captures. Barruel, who now manages Taylor’s collector list, hosted the artist’s first solo show in spring 2021 at Nationale, I hear voices from the other room, but I can’t make out the sounds. Figures in these drawings feel purposefully out of place, depicting the disquieting social interactions Taylor often finds themself in.

“The person doesn’t totally matter to me, it’s more about the emotion that they’re carrying.”

With Breathe when you need to, Taylor’s second solo show at Nationale, which ran in June 2022, they took on the subject of masking. In the autistic community, the term masking is used to name behaviors one might invent or attempt to assume to fit into a neurotypical world. Examples present as affected speech, mimicking gestures, and also as “stims” (self-stimulating behaviors), suppressed physical impulses that result in repetitive movements, words, or phrases used to block out overwhelming sensations. Canada’s Autism Awareness Centre describes masking as “a social survival strategy.” Unmasking, then, is an attempt at “removing layers of rigid social programming,” as Hannah Krafcik described it, writing about the show for Oregon Arts Watch.

Taylor approached that show as a dialogue with the French artist Claude Cahun (1894–1954). Cahun’s writing and photographic self-portraits commented on the role of gender as a mask, on the binaries that encourage people to adopt ill-fitting genders, and on the invisible power structures that the absence of space for transgender people creates. Taylor’s series of self-portraits also sought to create interstitial space, both in terms of gender and neurodiversity.

People Needing Other People

Pace Taylor’s voice is delicate. They pause before answering questions, and then speak quickly. The interview process to produce this article was a strain for them, and some of it was carried out over email. Standing in their studio, though, gesturing at the portrait of Judy/Madeleine in scene with a disco ball, they appeared confident, resolute, and at home. This may well have been a mask; later, they said they can often be their own unreliable narrator under pressure.

“It’s a lot of effort to communicate with people,” they say. “I had a lot of shame around feeling stupid for a lot of my life—being the quiet kid growing up and not having the resources to explain how I was thinking through things or feeling things.” Their work is a way to ruminate on interactions, conversations, the unspoken moments that define what it is to exist with other people. “By doing these drawings,” they say, “I’m really getting to meditate, to just sit with those feelings and try to actually figure out how I am feeling about my relationships with people and with the world.”

Their Los Angeles show, the one using Hitchcock as shorthand, Dancing Feels a lot like Falling, builds on the ground laid by their previous work, interrogating how society, and our interactions with others, shape who we are.

Taylor has described the movie as being about a detective falling in love with a person who doesn’t exist. Judy, viewers eventually learn, has been hired by a man to impersonate his wife, Madeleine, in a scheme to make Scottie, the retired detective played by James Stewart, a witness to the wife’s manufactured suicide. But Scottie falls in love with the fabricated woman, and is hospitalized in a manic episode after the faked death. When he chances upon Judy months later, Scottie doesn’t see at first that she is the same woman, but he sees the potential to make her into that same woman. Which he forcibly does.

Collecting material, Taylor reflected on their own experiences of anxiety and hypervigilance. They don’t much go for dance nights these days (“I used to self-medicate with alcohol to drown out the extreme stimulation”), but their previous experiences with a roving underground club called, fittingly, Judy on Duty, came to mind.

“Nightlife spaces are this place where we bring ourselves in a very raw form, and I think we can be quite moldable in that state,” they say. “We have a lot of expectations of who we want ourselves to be in spaces like that, how we want people to perceive us. So many people are looking, and it’s about desirability.”

In the artist’s statement, they wrote: “I’ve found myself participating in this desirability dance, leaning into an idealized version of myself.... At times, that version of myself has permeated into relationships, and I’ve willed myself to become another person, only to find myself lost.”

Things Left Undone

Asked, in an email, how their identity affects their art, Taylor replied: “Even if a drawing or a body of work isn’t explicitly about being trans or neurodivergent, it’s still evident in the way I made it. It’s there in the way I choose colors, or my relationship with physicality and sensuality, as well as the way that I think through subject matter.”

In the interview they gave to Oregon Arts Watch, Taylor mentioned the concept of asking viewers to set aside their own gender identity when viewing their pictures. The emotional weight of the figures should have enough “connective tissue,” they said, for all viewers to see something of themselves.

In this way, their work does have an effect on raising awareness around neuroqueer narratives, but the starting point always comes from within. They recoil from the word activist: “I’m not trying to force my ideas on other people,” they say, “but more so just explain how I’m feeling about something and let other people come to their own conclusions.”

The artist Lisa Congdon, who has become something of a mentor for Taylor, calls their work voyeuristic, referencing the pull of the subtly presented but immensely palpable erotic intimacy in the drawings. She finds it extremely vulnerable, a theme she notes is reflected by Taylor’s choice of medium: soft pastels are widely regarded as difficult and unruly. “You have to let go of a lot of control when you use a medium like that,” says Congdon.

Voyeur is a word that came up in a previous artist statement on Taylor’s website, too. They wrote, “In these drawings [I am] distilling years of being a witness, and sometimes a voyeur, to other’s relationships....” Attempts to make sense of others’ relationships—and crafting fictional relationships in their drawings almost as case studies—winds up, however, resonating quite profoundly with the people they sought to understand at the outset.

“It’s a lot of effort to communicate with people. I had a lot of shame around feeling stupid for a lot of my life—being the quiet kid growing up and not having the resources to explain how I was thinking through things or feeling things.”

“The pictures that they make are so personal, but they also feel accessible to complete strangers,” says Cody Evans, Taylor’s romantic partner, who works in deconstructing vintage homes to salvage old-growth lumber. The two met working at a plant nursery five years ago, and now share a duplex. Evans articulates the pull of Taylor’s drawings as “seeing something or witnessing a relationship, an intimate moment, regardless of whatever romantic connotations that you don’t fully understand, and wanting to understand it. Wanting to connect with other people and not really being able to find the door. And so that sort of meditation on those moments of confusion of social dynamics or intimacy creates an opportunity to, like, open the door.”

Barruel remembers sitting in her gallery at the reception for Taylor’s first show, where some viewers were moved to tears. One was David Whitaker, a collector from Boise, Idaho, whose wife is a doctor practicing gender-affirming care. For Whitaker, Taylor’s work offers a distinct and important perspective of transgender narratives. He mentions that a lot of work on the subject is designed to make you feel uncomfortable. This is good, he says, and necessary for starting conversations, but Taylor’s work “is another viewpoint into the same type of feelings and emotions and relationships.” Above all, he feels a deeply human connection to the four Pace Taylor drawings that now hang in his family’s home. “The work presents anxiety in a way that isn’t stressful,” he says. “The sense of feeling alone in a room where there’s other people, you know, that’s there.”

“I’m organizing all of my pastels by color, finally,” Taylor says, opening the door to their studio in early December. This seems to be a big event, the broken bits of crayon-looking drawing implements shuffling between different trays. They’re all covered in dust, so it’s tough to tell that they’re different colors at all, from afar.

The November opening in LA was filled with new faces, Taylor says. Collectors, artists they had only met online, and Barruel and Evans all hung out around a taco truck in the parking lot. It was late fall, but it was also LA, and sunny at 6 p.m.; the comedian Maria Bamford was there, too. It was busy: a party. But inside was quiet, a white-walled gallery with hushed voices and concrete floors. Taylor made their way between the two spaces, shifting when either became overwhelming. People wanted to talk about the work, a refreshing change, Taylor says, having feared it would be lots of trite hellos and thank-yous. “I don’t think I was expecting to enjoy the opening as much as I did,” Taylor says.

Energy in the studio is very much on-to-the-next. Taylor was awarded the Don Bachardy Fellowship at England’s Royal Drawing School right after getting back to Portland. The fellowship runs for two months in the spring, in East London. They’ll study in a Victorian loft on the school’s Shoreditch campus, attending lectures and taking in the city. Barruel says she has the last show of 2023 saved for Taylor at Nationale, and they’re participating in several group shows in between.

The walls of the studio are filling up with new work; Hitchcock is in the rearview. Taylor has been reading Joan Didion’s Play It as It Lays, and the line “I try to live in the now and keep my eye on the hummingbird” is stuck in their head.

Asked again about Vertigo, Taylor says: “The thing with that movie,

too, is that there’re actually so many plot holes. It really doesn’t make sense if you really investigate it. But I love that, because I also feel like, in my work, a lot of it doesn’t totally make sense. But the feeling still comes across.”