Oregon Poet Laureate Anis Mojgani Is Rewriting the Role

Image: Lars Leetaru

“Hi, y’all!” Anis Mojgani, Oregon’s poet laureate since 2020, beamed from his studio window six feet above the sidewalk. About 100 people sat below in folding chairs, with more spilling into the street, their shadows long in the sunset. Mojgani slid his square glasses up the bridge of his aquiline nose, which had the effect of turning down the volume on the audience. The crowd’s hush confirmed the unlikely: yes, these people were here to listen to poems.

Poems at Sunset out a Window began in spring 2022, after Mojgani read a few poems to a friend from the window of his studio on SE Yamhill Street. Portland was just lifting mask mandates, and many were wary of indoor events. His friend suggested others might like to hear poems outside. The free event grew fast, with performances out his studio window every other week or so. This night in March marked the opening of season two, following a break for cold weather.

Mojgani leaned out the window wearing a winsome smile covered by a few weeks of beard, shuffling through a manila folder of loose papers. His voice boomed loud and round as he began a version of his poem “Out of the Garden.”

Sometimes, I would lay in the garden and pretend I was a carrot

The crowd laughed on cue. Then he was a head of lettuce, then a rabbit. He picked up speed.

Sometimes when in the garden I was a rock

wishing I were two rocks

was sometimes becoming three rocks

His volume raised to a yell. Leaning back. Leaning forward. As a rock, he waited for a year, hundreds, even thousands of years, for someone to collect him, to take the rock that he was into their home. The silence hung between lines. His tone was severe, quiet.

In winter I would lie

in the garden and sometimes pretend I was something other than myself

A carrot

A rabbit

An echo of something bigger than the shade over my heart

Chuckles floated up into the trees. His countenance softened, solemn, and his elbows fell against the windowsill.

Sometimes in the garden

night would arrive

holding cupped in its hands the moon soft cheeked and full

glowing like the face of an orange skinned woman in a more orange dress

Nobody laughed. Nobody changed the cross of their legs or cracked their knuckles.

and the enormous night would use the moon to tell me you are like how I

am and see how bright my body sometimes becomes

So what exactly does a poet laureate do? Nobody seems to know. Mojgani, 46, says that most people conclude, “Oh, well that sounds big and important,” implying that the position is a lofty perch. “Good job!” they tell him blankly. But they’re lost as to what it means, just as many are lost as to

“exactly what is a poem or what isn’t a poem,” he says.

In Oregon, a tightly knit job description often appears in newspaper clippings: “The Oregon poet laureate fosters the art of poetry, encourages literacy and learning, addresses central issues relating to humanities and heritage, and reflects on public life in Oregon.” This sounds wonderful, important, and civic-minded—and so imprecise as to be meaningless.

Oregon’s poet laureate is supposed to perform 20 public readings annually. Across the 47 states that have laureates, the role is similarly autonomous. Laureates are state-funded, usually via arts grants, and receive a stipend ranging from $10,000 to $15,000; it’s not an official job. In Oregon, the governor appoints the laureate. There are some additional poet laureate positions devoted to specific cities and counties, though not in Oregon. (Portland’s “creative laureate” title, launched in 2012, is multidisciplinary—its holders have been involved in photography and visual art, storytelling, music, dance, tattooing, and more.) Initially, most were lifetime appointments, but almost all are now two- or four-year terms—two in Oregon. Mojgani, 46, is in the middle of his second term.

Ostensibly, there’s room for inventive outreach, and as many incarnations of the position as there are laureates, though in practice, the role has been more sedate, reserved for the “twilight” years of an esteemed academic career. The nine laureates who held the role in Oregon before Mojgani—including William Stafford, a prior national poet laureate, and Edwin Markham, namesake of an elementary school in Southwest Portland—had an average age of 67 when their tenure began.

But around the country, the staid post is increasingly a platform for diversity and inclusion.

Emanuelee “Outspoken” Bean created a community spoken-word album during his time as Houston’s poet laureate and founded a festival uplifting Black writers and poets. Lee Herrick, California’s first Asian American poet laureate, invites local social justice or civic engagement organizations to speak at every reading he gives around the state. Paisley Rekdal, Utah’s laureate from 2017 to 2022, built a digital geographic database of Utah poets and writers to represent a literary sense of place.

Nationally, Ada Limón, who’s 47 and Mexican American, is the first Latina US poet laureate. The title of national youth poet laureate was first bestowed in 2017 on Amanda Gorman, then 19, a Black poet from Los Angeles who would make waves four years later at Joe Biden’s inauguration with her viral poem “The Hill We Climb.”

Mojgani is the first Black and first Iranian laureate in Oregon, and the third person of color that the state has appointed to the role. He’s well aware that he’s “not your average poet laureate.”

In conversation, Mojgani flips between colloquial and overly proper vocabularies. He says things like “at this juncture,” “the fall previous,” and “thanks for doing such.” But he also says “like” often and gets “pumped” for things. His reaction to being named laureate? In an octave above his normal register: “Oh my God! How … how rad. This is so weird. This is so cool. I’m elated!”

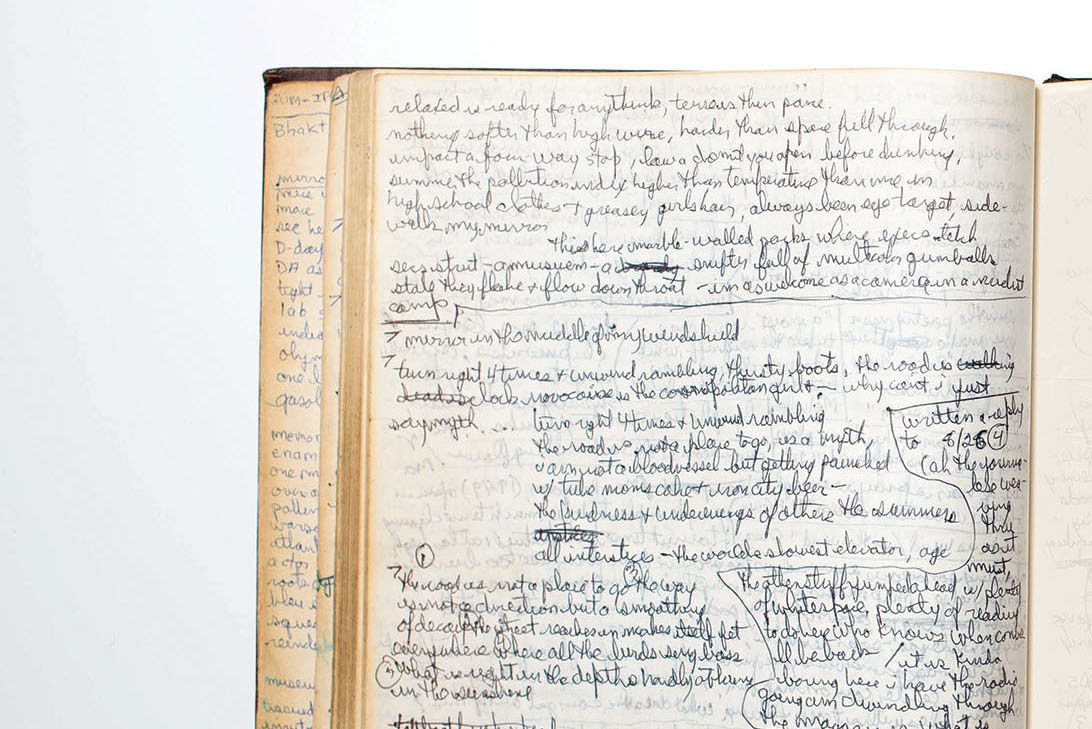

Laureate was far from his first accolade. Mojgani came up as a slam poet and holds national and world championship poetry slam titles. He’s also the author of several books of poetry, into which he weaves a fair amount of his biography. The Pocketknife Bible (2015) is a surreal account of his New Orleans childhood; it’s a book-length poem written in the first person that explores his inner life as he begins to understand his ethnic and racial makeup.

I know some people say this sometimes

—cut from the same cloth—

and I wonder if the night sky is that cloth.

In the Pockets of Small Gods (2018) is a more fractured narrative of individual poems about the grief of his dissolved marriage and the four years he spent in Austin during it (2011–2015), as well as the loss of one of his closest friends to suicide.

Sometimes everything is a rock. My wedding ring. Two stems of Craspedia

saved from my boutonniere and her bouquet. The three of them together

in a little jar. Sometimes feathers.

His subject matter is vast, but most, if not all, of his work hovers around human connection. His poems are not so much explicitly about love but what he calls the “wordless word for what is underneath love”: “the ways in which we feel towards other people … friendship, sexual, romantic, parental—whatever it is, it’s all coming from this same wordless thing underneath.” His sixth collection, The Tigers, They Let Me (out July 19 from Write Bloody Publishing), includes a poem titled “To the Sea” about giving space for rambling,

—which really I think is a beautiful softness

of being human, trying to show someone else

the color of all our threads, wanting another to know

everything in us we are trying to show them—

This more or less articulates his strategy as poet laureate: creating space to share the nearly wordless that’s inside of us with others—an instinct that was initially hamstrung by COVID lockdowns, which landed just before he was named poet laureate in April 2020. The state responded optimistically. “Anis is the pragmatic optimist Oregon needs in these unprecedented times,” then-governor Kate Brown said at the time. “His words breathe fresh air into the anxiety and negativity that we all feel.”

In his first year, he leaned into socially distanced projects. First, he enlisted several of Oregon’s previous poets laureate to record dozens of poems for his poetry telephone hotline. Thousands called in to hear Mojgani and his predecessors’ voices on the other end—poems to get you through the day. Soon after, he collaborated with the Timbers on a poem about “Soccer City,” and wrote the libretto for Sanctuaries, an opera about gentrification in Albina. He hosted several poetry-themed Pedalpalooza bike rides called Spoke’n Words. The Academy of American Poets found this work impressive and granted him a $50,000 Laureate Fellowship.

As the end of his first term approached in early 2022, traditional public appearances remained either entirely out of the question or largely compromised due to social distancing. Brown opted to extend his appointment for a second, two-year term, allowing him to “fulfill his vision as Poet Laureate.”

Mojgani’s reaction to the second appointment? “Oh cool. I get to do this again? Fuck yeah!” Before quickly amending, “Perhaps this is the thing to do.”

Inside the Arlene Schnitzer Concert Hall at the end of April, Mojgani reigned over a packed house of bookish teens and their families, teachers, and peers. He explained that the event, Verselandia!—the championship high school poetry slam he hosts with the local nonprofit Literary Arts—was essentially “a big trick to get a bunch of rubes, as it were, to come listen to poems.” It has not escaped him that this could be an apt description for the laureateship itself. He wore a baseball cap, a chambray button-up with rolled sleeves, and sneakers. He briefly explained the mechanics of a poetry slam to said rubes, and concluded, “We’ll pick it up as we go along.” In turn, 21 teenagers recited poems with a dramatic reverb, framed by the hall’s colossal velvet curtains and preposterously detailed moldings.

After each three-or-so-minute poem, Mojgani came out from backstage and counted off, jubilantly, “Three! Two! One!” And the five judges would hold up numbers out of 10 on folding scorecards. Then he would yell, “Applaud the po-et!”

He was, perhaps, trying to imbue these teens’ forays into performance poetry with the humor and elated audience response that fueled his own early career. Mojgani had no “formal” poetry training, instead studying comic book illustration and performance art (“essentially acting”) in the late ’90s and early aughts at the Savannah College of Art and Design; poems were one of many creative outlets. The Urbana Poetry Slam eventually brought him to New York, and on a lark, he gave a weekend reading in the basement of CBGB—an unfinished, world-famous room, every inch plastered with show fliers and graffiti. It would end up changing his life.

“There’s no way he could have seen the reaction and not have started to take it a lot more seriously,” says Adam Greene, Mojgani’s oldest friend and former roommate.

He was “unintimidated,” “particularly disarming,” and “infectious,” remembers Cristin O’Keefe Aptowicz, cofounder of the Urbana slam and now a New York Times best-selling poet and writer. “His early style was very comedic,” she says.

From an early crowd-pleaser:

In my underwear I write poetry

two headed poetry

three legged poetry

…

I come from the moon

Neil and Buzz

and that third guy walked across my tummy

He moved to New York soon after, but the struggle of the city grated on him. A year later, he followed friends to Portland, working at the now-closed Random Order Coffeehouse on NE Alberta Street, and catering at the Oregon Zoo, before embarking on a Kerouac fantasy to “just go be a poet,” stringing together events and hosting gigs at community centers and schools and concert halls, traveling up to six months a year. He initially perceived the laureateship as a sign from the universe to keep doing more of the same.

Rather than appearing onstage as a character, he maintains an enchanting consistency between Mojgani the performer and Mojgani the guy shaking hands with kids after the show. Though they sometimes ask if his glasses are part of his costume as a poet, Mojgani suspects that the kids are receptive to him precisely because he doesn’t put on a metaphorical poet’s costume. “I’m not song-and-dancing to try to get you to like me,” he says. “I’m not, like, putting on a facade.”

“He makes it very clear that there’s a comfort where he is. And there’s an ease and joy where he is,” says Hanif Abdurraqib, an award-winning writer and recipient of a MacArthur “genius” grant, and a friend of Mojgani. “It makes it kind of irresistible to want to get to where he’s at … to continually tap into that level of trust with others is massive.”

He wields that trust offstage as well. Mojgani sits on the board of Literary Arts, where he’s the chair of the Oregon Book Awards council and works with the organization’s youth outreach programs. But executive director Andrew Proctor says that Mojgani’s true influence is rooted in this uncompromising authenticity, and the value that genuineness builds in a highly visible, politically appointed post.

“It’s really important that people see him, you know?” Proctor says. “His identity does matter in this equation, right? It does open doors. He has made space; he has redefined, by virtue of his talent and his identity, what a poet laureateship is.”

Mojgani understands that visibility is foundational to progress. Institutional presence matters. Over a slice of pizza at Sizzle Pie after the first Verselandia!, in 2011 at the 300-seat Mission Theater, Mojgani and Proctor set their sights on the Schnitz. Slowly, they moved the annual event to the Wonder Ballroom, then to the Newmark Theatre, and eventually made the considerable leap (from 800 seats to 2,700) to the Schnitzer in 2017. Getting the event into the city’s classiest performance hall, and redefining whom that venue features, was the goal from the start.

At the Schnitzer, one teen’s poem addressed how the venue put “some importance on what we [kids] have to say.”

“Exactly!” Mojgani later exclaimed.

These days Mojgani is inching even closer to his audience members, who can once again sit within six feet of each other. He’s fulfilling the official duties of the laureate in spades, but he’s also pushing both the form of poetry and the notion of a laureateship, constantly creating new events and projects and opportunities, moving the role into new shapes, and reaching toward underserved audiences.

During a pause at the end of the Schnitzer show, while the judges tallied the night’s scores to declare a winner ($1,000 cash prize), Mojgani shared a poem, “Closer.” He explained that although he wrote it years before the pandemic, he’s found retroactive meaning in it.

“Come closer,” he commanded, warmly, with a vulnerable smize. “Come into this. Come closer.”

The crowd was visibly exhausted. The students’ poems were uniformly devastating and beautiful. Many were calls to action following their own student walkouts protesting gun violence earlier that same month. There was a proud-yet-sobering feeling as the audience leaned in for guidance.

Later, he explains that he enjoys the confusion this ambling poem incites: “You don’t know when the poem begins and the non-poem ends.” Likewise, when his term as laureate ends next spring, it will be hard to discern—the post being pretty much the same thing as his “actual” job, after all.

“I see teacups in your smiles, upside down, glowing,” he continued, head cocked, ardent.

Your hands are like my

heart. Some days all they do is tremble. I am like you. I am like you.