A Journalist Dives Behind the Scenes of the Art World

Bianca Bosker grew up in Portland and now lives in New York City.

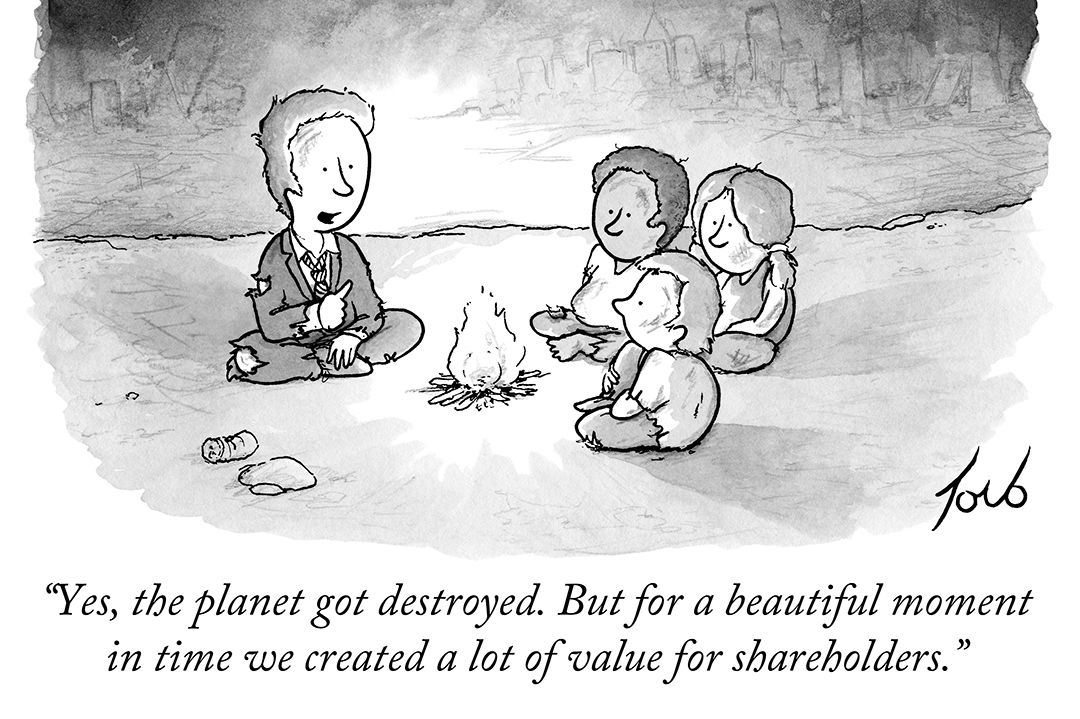

If an assfluencer—an influencer famous for posting pictures of their booty, that is—sits on your face, and she has an MFA from Columbia, and this happens inside the hallowed walls of an art gallery, is it art? This age-old question—what makes art art?—is at the core of journalist Bianca Bosker’s new book, Get the Picture.

Embedding herself in New York City’s modern art galleries, studios, and museums, she tries to grasp why art matters, seeing it, at the book’s outset, as either revered by a cultivated few or misunderstood by the masses. She identifies with the type that begs artists to “just tell us what you mean!” but wants to feel the “fireworks” promised by insiders. Maybe, she muses, she can study the enigmatic scene and then “explain it to the rest of us.”

So, what’s the deal with art, anyway? What the query lacks in sophistication it makes up for in approachability. Bosker's last book, Cork Dork, a New York Times bestseller, evaluated the wine industry similarly; here she looks to understand art by treating it as a subculture. She limits herself mostly to New York City (her adoptive home, after growing up in Portland), and to modern visual art—paintings and sculpture, save the odd avant-garde performance artist (“Are the Kardashians performance artists?”). At times gossipy, at times salacious, it’s a page-turner. Spoiler: this is not the book that finally cracks empirical measurement of art’s quality or purpose. But it is an important look at the machinations behind art’s role in today’s society.

Though it’s not quite a pulpy expose, Get the Picture functions as a sort of update to Tom Wolfe’s The Painted Word, the controversial 1975 book in which he argued that art had grown so focused on ideas that the actual physical “art” of it had fallen by the wayside. Wolfe is often credited with inventing the first-person, opinionated style of journalism Bosker is using here. And though she gets her jabs in, she diverges by keeping her nose pressed to the glass, while The Painted Word came in from on high, telling the art world what it was.

We ride on Bosker’s shoulder like a pet parrot. We experience Amanda Alfieri’s, the Ivy League performance artist (our aforementioned “assfluencer”), conflictingly moving performance firsthand—when she sat on Bosker’s face. Time blurred. It conjured complicated ideas about parasocial relationships and hyper-sexualized modern beauty standards, while simultaneously making Bosker feel warm, safe even.

Bosker positions herself as an avatar, a malleable everyperson who, like you, thinks art is totally great. “There I was,” she writes in the first few pages, with a tinge of malaise. “Early thirties, living in New York, with a nice career in journalism and a flawlessly optimized routine, albeit one that didn’t make room for art.” That “flawlessly optimized” life left Bosker wondering, “What if art could stop the walls from closing in?”

Transfixed by indications that the art world is an abusive, unethical swamp, and by its tight-lipped denizens holding their tongues more solemnly than national security advisors, she embarks.

A hard-won internship with a quixotic young gallerist named Jack Barrett opens the gates. He’s extremely serious about the purity of the art he shows, but operates his gallery with the elitist cool of a fashion label, fretting over the punctuation of Instagram posts and actively preventing foot traffic. Of the art world, he tells Bosker, “not everyone understands it. And that’s sort of what creates interest and intrigue.” Suspicions that Barrett’s uncompromised devotion might be subsidized comes in waves: his Acne sneakers, his Manhattan townhouse, his uncanny ability to navigate the world of the uber-wealthy.

Still, he teaches her how to fit in. Bosker hones a world-class “resting bitch face,” an ungenerous approach to conversation and compliments, above a quietly chic wardrobe. She learns that beauty is too easy to be taken seriously, both in art and life. She learns so-called International Art English, the “art speak” derived from awkward translations of French theory designed to weed out philistines like her. “Context” is the first answer she finds to her question of what makes art art. An artist’s CV and collectors, yes, but context is also about gender, ethnicity and nationality, sexual orientation, one’s ability to hang. It’s the indelible “cloud of names” that follows an artist and their art around.

Bosker feels the filter of context guiding her. Mistaking a drainpipe for a sculpture is a low point. Mistaking the live-in staff’s quarters of a Florida art collector’s home as an installation that evokes an “institutional and claustrophobic” feeling “with a creepy whiff of surveillance,” is worse.

She notes that the art world functions as a legal insider trading scheme, which Bosker observes while assisting painter Julie Curtiss, who is refreshingly unpretentious. Artists most often sell work through a gallery, which takes 50 percent of the sale. Auction houses move work between different collectors and institutions on the secondary market—transactions that pretty much never involve the artist. Curtiss was in the news because a painting of hers sold for $106,000 at auction. She tells Bosker she had initially made $600 selling the painting. Later, a painting Curtiss sold for $1,400 is auctioned for $209,000. Oh, and, talking money is terribly uncouth, if you’re taking notes.

In the closing section of the book, “The Vacuum,” Bosker works as a guard at the Guggenheim Museum, spending 40-minute shifts staring at a single piece of art. There she befriends an affable marble sculpture, The Miracle (Seal [I]), by the Romanian sculptor Constantin Brâncuși. She says hi to it when she comes into work, and comments on its mood day to day. Depending on your vantage, and the energy in the room, it’s a “toothpaste squirt,” a “trained seal balancing an invisible ball on its nose,” “a foot squeezed into a heel,” “a semi hard penis,” or “a sullen woman in a hijab.”

What does Mr. Brâncuși mean by conjuring all of these images? “Its meaning wasn’t a punchline, a definitive answer to be learned,” Bosker writes, subverting her initial plea for an explanation. “Its meaning was the richness of its company.”