The Ursula K. Le Guin Cat Book You’ve Been Waiting For

A giant in the world of science fiction and fantasy literature, Ursula K. Le Guin won her numerous awards—eight Hugo, six Nebula, a staggering 25 Locus—not for her creation of the Ansible or world building of Earthsea, but for her profound understanding of humanity. Through the trappings of magic and distant human worlds, the beloved Portland author explored sex, anarcho-communism, colonialism, and Taoism, among other themes. While many readers discovered Le Guin through the voice of Ged in A Wizard of Earthsea or Shevek in The Dispossessed, others began with Thelma, Roger, James, and Harriet, the titular flying felines of the series Catwings. Le Guin published this small, illustrated series between 1988 and 1999. Written for young children, the books told of winged cats moving from the big dangerous city to the countryside.

Le Guin wrote a few other kids’ books about cats. A Visit from Dr. Katz (1988) was about the healing power of feline affection. Cat Dreams (2009) explored their sleeping worlds through rhymes and beautiful illustrations by S. D. Schindler, who also provided the art for Catwings. But she never centered cats in any of her more than 20 novels or giant catalog of short fiction. Perhaps this was because she understood cats as well as she understood people. Cats live each moment immediately and, too often, they live but briefly relative to us. Poems, sketches, doodles, and correspondence seem better suited to their ephemeral nature. Out October 7, Ursula K. Le Guin’s Book of Cats (Library of America), certainly makes that case. The posthumously assembled collection of all of the above, some of it published here for the first time, celebrates the author’s shared or witnessed moments with her feline friends and acquaintances. Some are whimsical and silly, others tranquil, observational. Naturally, a few deal with loss.

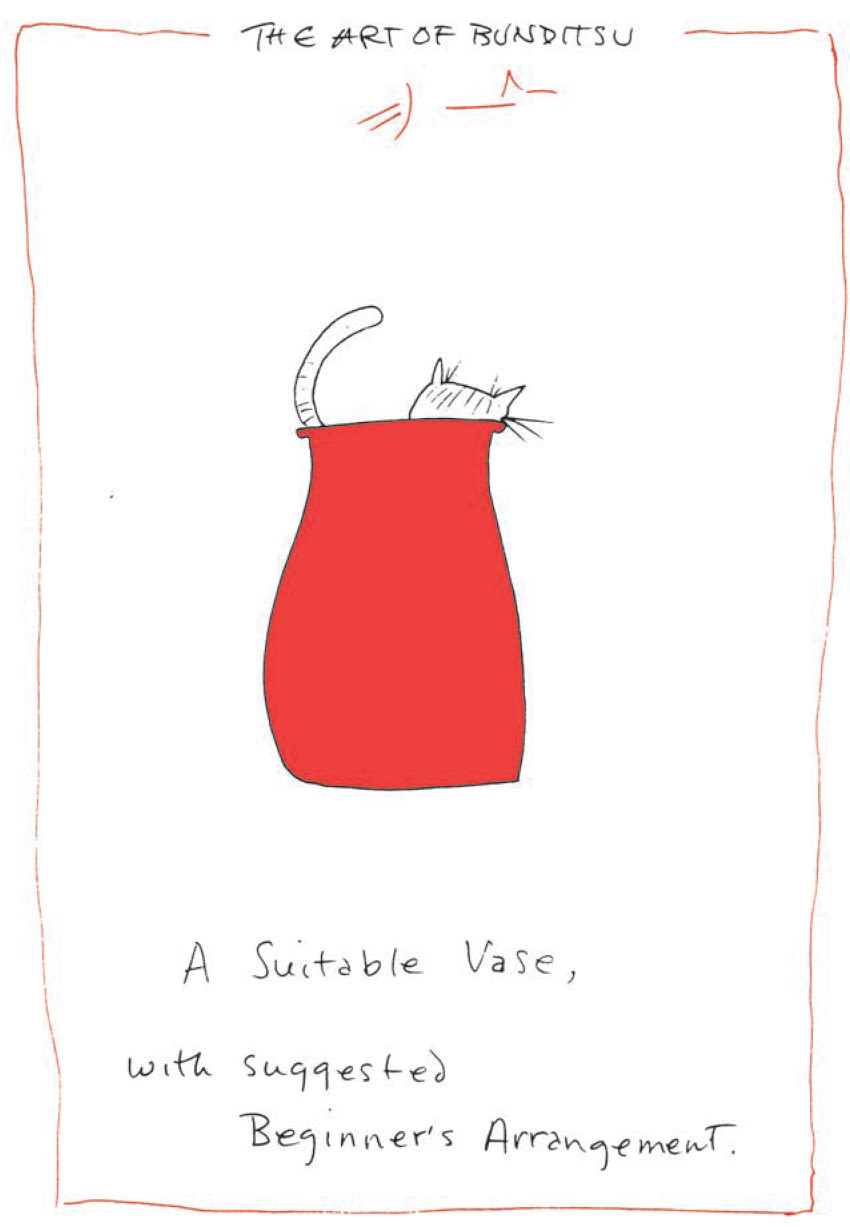

Much of the book’s humor comes from Le Guin’s sketches, like the illustrated guides to “Japanese Bundistu” and Cat Tai Chi. Her Balloon Cats postcards depict wide-eyed, rotund kitties blowing in the wind or meeting a school of inflated fish. It’s amusing to learn that the seminal author of The Left Hand of Darkness spent her spare time doodling stumpy drawings of her pets. Sitting with this book, it also becomes clear that the deep attention she paid to small moments, however trivial they may seem, played a critical role in her ability to render entire universes.

Le Guin’s wry humor and world view also shine in a short comic, The First Adventure of Super Mouse. Donning his magic cloak, Clark Clark the rat (not mouse) receives flight, enhanced strength, and the ability to see through cheese as Super Mouse. He uses these powers to accost a feline threat, Pussa the Great, but their melee ends in stalemate, and he realizes that violence isn’t the answer. He instead gives butt scratches and treats before bequeathing her a magic cloak of her own. Now allied, the duo vow to defeat “the evil forces of Bullying, Bigotry, Ignorance, and Finkiness.” The final panel shows them flying over a cityscape with a box labeled “Cheese 25 LBS.” Even in a silly little comic about a cat and mouse, Le Guin’s views on what constitutes true strength are clear.

Reading the “correspondence” between Le Guin’s cat, Lorenzo, and her daughter’s cats, Frederika and Opal the kitten—a series of philosophical dialogues—it’s easy to imagine that these are actual transcriptions, as the book claims. The older cats discuss the Five Deliberations that all cats strive for. Chief among them is Sameness, a need for things to remain familiar and undisturbed (especially regarding the dreaded Cat Carrier). Though clever and amusing—and resembling other narratives like the viral YouTube video Sad Cat Diary—the letters reveal how much Le Guin and her daughter considered their cats’ perspectives, needs, and unique personalities. Opal is more interested in playing with human underwear than learning any of the Deliberations.

More than her comics and correspondence, Le Guin’s poetry shows how connected she was to the cats in her life—those she lived with, those she lost, and even ones that she barely knew, as evinced in a series of poems about her fraught relationship with a visiting neighbor cat. Other poems touch on the lives of her companions, from the kittenish predator hunting mice and birds to the bone-weary senior choosing warm laps and fireplaces over exploration. And the joy and tragedy of cat ownership rings through the eulogy “A Little Death.” But Le Guin never veers into the maudlin. Even her saddest poems, like all her work, are graceful and reserved.

He sent his life forth as the crippled tree

puts forth white flowers every year

upon the dying branch. He knew the way.

Every cat lover will likely recognize a furry friend in a drawing or line of poetry in Ursula K. Le Guin’s Book of Cats. Considering the ubiquity of tuxedo cats in homes, more than a few will see a likeness in the author’s ode to her last cat, Pard, without whom “life would be hard.” The book closes with biographies of each cat that shared a home with Le Guin, and Pard’s entry details how he completed Le Guin’s husband Charles’s path to becoming a “cat dad.” The author’s compassion and adoration for these wondrous animals—like the deep empathy for humanity that defined her work—appears to have affected those around her, as well. Pard survived both Ursula and Charles, and, according to the official Ursula K. Le Guin Instagram account, is being doted on by a loving family today.