A Shameless Peek at Portland's Money

Image: Jack Black

Ever since 1843, when William Overton cut Asa Lovejoy in on his 640-acre land grab—for a quarter!— Portland’s attitude about money has been considered, shall we say, nonchalant at best. Portlanders are scrimpers, not splurgers. They care more about balancing work life with family life than about acquiring the material riches afforded by the rat race. (Right?) And unlike those brazen, Botoxed Angelinos down south, Portlanders don’t like to talk about money. That would just be too gauche.

Well. Call us gauche. Because we’ve gone and posed all those forbidden questions—like “How much money do you make?” And “What did you buy with your millions?” And “So how does it feel to be flat broke?”

To our great surprise, in spite of Portland’s rep as a city given to monetary modesty, people talked. From lottery millionaires to a drag queen with a penchant for vodka martinis and a family who made a pact to buy nothing new for an entire year (not even vacuum bags), the people in these pages prove that Portland’s attitudes towards money are as diverse as the city itself. Lucky for you, now that we’ve gotten all the juicy answers, all you have to do is take a look.

GILDING THE CITY

Welcome to Portland! Please recycle. And keep the bling to a minimum.

Image: Jack Black,Jack Black

EMBLAZONED with the interlocking C’s that are Chanel’s famous logo, the $3,300 black leather purse is positively voluminous. There’s enough space inside for a bowling ball—perhaps even two. You’ll find the bag for sale on a well-lit shelf at the new Chanel boutique at Nordstrom, Pioneer Courthouse Square, where it shares real estate with a $400 gold belt and a $4,200 clutch that is accented with delicate chains. Although Chanel only opened in August, one well-coifed saleswoman reports that business is going swimmingly. “We make sales every day,” she says. “It’s been extremely well received.”

In making the decision to open its fourth Chanel boutique in the country, Nordstrom execs undoubtedly took note of Portland’s increasingly monied demographics (the median household income was $57,826 in 2007, compared to $47,505 in 2005) and marked the fact that local high-end malls such as Bridgeport Village have been profitable. But mostly, notes Nordstrom’s spokesperson Kendall Bingham, the company listened to Portlanders themselves. “What we’re seeing is an increased desire for luxury goods,” she says, adding that the same holds for markets across the country. A Gucci boutique will open across from Chanel this spring.

The availability of such high-end brands on the local retail scene is but the latest evidence that Portland is slowly sloughing off its reputation as the only major West Coast hub where denizens don’t flaunt their wealth with designer plumage and bling. “Historically, Portlanders came from Germany, Scandanavia and [other] European cultures that aren’t exactly known for their ostentation,” notes Portland State University historian Carl Abbott. Even among the upper crust, he says, our city has traditionally been a “quiet, old-money kind of place.”

Some might argue that Portland was not just quiet, but that it actively disdained an excess of verve and flash. Consider the experience of Californian Ben Holiday back in the 1870s. Although the transportation tycoon built the railroad that linked the two states and opened up a market for goods, Portland’s downtown elite ostracized him and generally made his life miserable. His fatal flaw? He was “a bit too flamboyant, a little too sleazy and too suspect—too Californian,” as Abbott puts it. Once the railroad was up and running, Holiday went back to where he came from. (A tiny park near the Lloyd Center commemorates his temporary residency.) No doubt he was happier there, living among his own kind.

In present-day Portland, the Pearl District is, of course, the ultimate exemplar of our newfound peacocky ways. But the neighborhood hardly launched the trend. Long before Gerding Edlen transformed Henry Weinhard’s beer works into a locus for fine living, subtler signs that Portland was on the verge of a conspicuous-consumption bender were cropping up all over town. Consider, if you will, steak.

“I was like, $70 steak? Who eats a $70 steak?” notes one third-generation Portlander of Danish descent who grew up in Irvington, remembering the opening of Ruth’s Chris Steakhouse in 1995. Apparently, though, plenty of Portlanders were ready to raise their knives and tuck into fine cuts of meat. Morton’s the Steakhouse, where a double-cut filet runs $42, opened in 1998, and El Gaucho, which charges $84 for a 24-ounce New York strip and reliably attracts a starch-collared, after-work clientêle, opened in 2000.

The shift in Portlanders’ attitudes about wealth cannot, however, be measured by the arrival of luxury goods and services alone (though those little blinis topped with glistening beads of caviar that Saks Fifth Avenue served to 1,200 during its 1990 opening preview were, for months afterwards, the talk of the town). There was also the arrival of certain people, including social connectors John and Lucy Buchanan. In 1998, the arts-development power couple from Memphis succeeded in raising a whopping $30 million to build the Portland Art Museum’s new wing by brazenly employing tactics heretofore unheard-of in the quaint world of Portland fundraising, including aggressive mass-marketing and over-the-top galas. Sure, there were plenty of tsk-tsks behind the Buchanans’ backs—but donors were, for once, all too willling to dispense with modesty to support the cause. Besides, the parties were absolutely fabulous.

The Buchanans have since departed for San Francisco, but they helped usher in a new era of charity. “Oregon always had a more populist tradition of giving,” says Greg Chaille, president of the Oregon Community Foundation, a statewide nonprofit that administers charitable funds. In other words, Oregon’s philanthropists subscribed to the idea that organizations should be built with the combined efforts and contributions of many people—not funded outright by a few mammoth hunks of cash. “Getting too far out in front with the big gift was seen not just as bad taste, but also as discouraging others from doing their part.”

Today a more spirited culture of charity pervades, as evidenced by the increase in large gifts to local nonprofits and schools, including Lorry Lokey’s recent $74.5 million gift to the University of Oregon and Hollywood Video founder Mark Wattles’s $1 million donation in 2001 to the Lents Boys and Girls Clubs. (It’s now called the Wattles Club.)

While hardly reaching the sort of seven-figure heights seen in Seattle, Los Angeles and San Francisco, the escalating prices of real estate were another glaring marker of shifting economic realities. When, in the summer of 2001, five Portland homes not located in the West Hills or Lake O sold for more than $1 million within a few weeks of one another, it made newspaper headlines.

All of these anecdotes suggest that Portland, the Inconspicuous City, is officially a thing of the past.

Or is it? Undoubtedly the increasing influx of “in-migrants,” those people who move here from somewhere else in the country, will continue to shape and shift the city’s cultural milieu. According to Portland State University’s Metropolitan Briefing Book, net in-migration accounted for 41 percent of Multnomah County’s population growth between 2000 and 2005. But Joe Cortright, an economist with Impresa Inc, a firm that conducts economic analyses for clients, thinks Portland is not in any real danger of becoming the place that many residents fear it will be: a culturally homogenous city that embraces an ethos of self-interest.

In fact, he says, Portland is less homogenous now than it ever has been. What we’re seeing now is “more varied consumption patterns rather than a fundamental shift in values,” he says. And what better thing for a community that professes to embrace diversity than to embrace what he calls “lifestyle eclecticism?” Portland is the kind of place where, he notes, “you have Saks Fifth Avenue and also a large concentration of people committed to voluntary simplicity. You have the towers in South Waterfront but you also have strong co-housing communities…. It’s not that there are just more rich people,” he says. “There are more different people.”

Still, the rise of Portland’s upper class makes some people profoundly uncomfortable, and there is no better sign of the growing tension among the classes than the some 21,000 pages of community comments that were collected for Mayor Tom Potter’s VisionPDX project, which aims to shape the city’s future based on input from its citizens. The comments are contained in cheap white plastic binders and kept in the Bureau of Planning on the seventh floor of the 1900 Building downtown, near the cubicle of one Cassie Cohen, a casually attired employee who helped write some of the summary reports and who offered me a cup of herbal tea from her personal stash when I visited.

Throughout the collection, whether the topic is housing, livability or “small-town feel,” the Pearl District remains a top target for those unhappy with the way our metropolis has, and has not, progressed. “The increase in glass high-rises and the Pearl District culture doesn’t allow for people and lifestyles outside of the middle- and upper-class ideologies,” wrote one disgruntled citizen. Yes, Portland embraces diversity, such comments suggest—so long as people don’t go, you know, getting a little too Ben Holiday on us.

“What I got is that people are really focused on the non-monetary,” says Sheila Martin, director of PSU’s Institute of Portland Metropolitan Studies, who co-chaired the VisionPDX project. Indeed, once all the comments were painstakingly coded for content and intent, the results show that we strongly value “community connectedness and distinctiveness,” “equity and accessibility” and “sustainability” above all else.

It is hard to think of another city, should the same questions be posed to its residents, that would generate such a clear, values-based sense of itself. But are these values strong enough to bring tens of thousands of newcomers into the Portland fold? That’s about as easy to fathom as human behavior. But, hey, if you did just join our citizenry, and have the means to shell out $70 for a steak, let me offer some advice: Make sure it’s locally raised and hormone-free. We promise that you’ll feel better about the planet. More to the point, we’ll feel a whole lot better about you. —JD

THE WINNERS

Is hitting the jackpot all it’s cracked up to be? Four Portland lottery winners say yes. And no.

WHAT WOULD IT BE LIKE TO WIN THE LOTTERY? Few among us have not, at some point, indulged in the ultimate fantasy—thanks in no small part to the jaw-dropping amount of money that the Oregon Lottery spends on advertising to fuel our flights of fur-lined fancy. In 2007 alone, $10 million went to pay for print, billboard and TV ads that trumpeted the joys of winning and reminded people that profits from state-sponsored gaming help fund everything from state parks to education.

But to counterpoint those champagne wishes and caviar dreams, we found four Portland-based winners who say that having your lucky numbers drawn can, in fact, be stressful and even a little scary. Sure, they’re loaded—but, for better or worse, suddenly coming into heaps of cash is not what they expected. That old cliché about money not buying happiness? Yep. It’s true.

MARVIN RANSOM | $20.6 Million | July 11, 2007

SPLURGES: IRVINGTON HOUSE, GIFTS OF $30,000 EACH TO SEVEN RELATIVES; HAWAIIAN VACATION

Image: Stuart Mullenberg

After a multi-million-dollar win, most people would march into their boss’s office to deliver the Take this job and shove it! line. But not 43-year-old Marvin Ransom. Five weeks after he won the fifth-largest jackpot in state history, he returned to the kitchen of Stanford’s in Clackamas, and spent the day chopping vegetables and making vats of clam chowder. And no, he has no intention of quitting his $14.25-per-hour job.

“I want my kids to think, ‘OK, my dad came into some money, but he is still going to work,’” he says.

Sitting in the dining room of his Craftsman house in Irvington, which he purchased in August, Ransom recalls the times he has found it difficult to navigate his windfall. “This was all a lot of fun at first,” he says, “but it’s been really overwhelming, too. I’m somebody who likes to keep a normal schedule. I need to feel like a regular guy.” And for the whole of his life, “regular” has meant living paycheck-to-paycheck to provide for his family of seven. During the leanest of times, Ransom even bought a used washer and dryer with a canister of quarters he’d been saving for over 20 years.

The acquisition of wealth has not coincided with an extravagant lifestyle for Ransom and his family, nor does he think it ever will. “We still eat frozen pizza for dinner. We still buy the family-pack meat from Fred Meyer,” he says.

THE BENTLEYS | $17.2 Million | Aug. 27, 2005

SPLURGES: VACATIONS TO JAMAICA AND GRAND CAYMAN, CHRYSLER 300C, CHEVY FOUR-BY-FOUR TRUCK

Image: Stuart Mullenberg

John and Jackie Bentley would like to clear up a few misconceptions about winning the lottery. You might not do half the things you think you would, like, say, build a log cabin at the top of a mountain or spend top-dollar in the pursuit of a perfect golf swing. And while the stress of having to work does subside (the Bentleys retired soon after their win), other stresses take its place. Often your days are filled with meetings arranged by your financial advisors. You field plenty of calls from philanthropic organizations—and family.

“Everybody wants a piece of the pie. We donate to causes that matter to us, not to people who feel like we owe them,” says John. Like most lottery winners, the Bentleys have had to say “no” many times. For instance, there was the time a family acquaintance called asking them to invest in his failing countertop-installation company. Twice. “We hadn’t heard from him in five years,” says Jackie. “Who is he to call and ask for money?”

Turning down such opportunists often makes the Bentleys “feel like the bad guys.” But they are hardly miserly people: Days after they won, Hurricane Katrina hit, and they wrote a check to the Salvation Army. They’ve given money to the National Breast Cancer Foundation, and have also donated funds to various pet-related causes. (They share a home with four cats, a dog and a bird.) All told, they’ve dedicated around $100,000 to charity. “We were working-class people before and couldn’t really afford to help out,” says John. “But we only want to help people who are really trying to improve their lives. We’ve learned there’s a difference between assisting and enabling.”

STACY LOWRY | $5 Million | Jan. 8, 2000

SPLURGES: MUSTANG CONVERTIBLE, A MINI COOPER FOR HER MOM, A MUSTANG FOR HER DAD

Image: Stuart Mullenberg

“I never knew people could be cruel, or jealous or deceitful. Then I won the lottery,” says Stacey Lowry, who was working as a gas station cashier in Prineville, Ore., when she bought the winning ticket. “In a lot of ways, I think I lost my innocence.”

So ebullient was the then 20-year-old over her win that she agreed to allow the Oregon Lottery to use her face on billboards. A series of unhappy events followed soon thereafter. She was heckled on the street. Someone broke into and burgled her home in Bend—three times. Rumors about how she spent her money spread through town. “My favorite was the one about gigolos,” she says. “My least favorite was the one about me dying in a car wreck on my way to Vegas for a spending binge.”

But the hardest lessons concerned her relationships. “I had a lot of friends—I call them ‘the bad apples’—who took me for cash,” Lowry says. “There were times I would cry and ask, ‘Why do I deserve this?’ I didn’t want the lottery anymore if this is what I’m going to have to deal with. I’d rather struggle like everyone else. Be like everyone else.”

Today she lives in a modest Southeast Portland house, and the stash of Coach, Louis Vuitton and Burberry handbags she’s collected over the last few years (she’s recently pared them down in number to 35 from more than 100) are the only visible hints of her wealth. “The things that make me the happiest have nothing to do with the check I get every year for $250,000,” she says. “It’s going for walks to see ducks down the road or playing in the park with my daughter.” In other words, she says, the kind of experiences available to anyone, no matter their economic status.

THE DOVES | $8.2 Million | Dec. 2, 2006

SPLURGES: NEW HOUSE, COMPUTERS, DISNEY WORLD VACATION

Image: Stuart Mullenberg

“Winning the lottery is at the top of your wish list, and then you win and it’s like ‘Bummer, what’s next?’” says Rob Dove. “I’m sort of glad we didn’t win some crazy amount like $150 million. That would have been a headache.”

Rob’s worldview is staunchly pragmatic. The Troutdale native spent eight years as a medic stationed with the Marine Corps during Desert Storm in the early 1990s, and four years as a nurse at St Vincent’s hospital. As such, he is under no illusion that money alleviates suffering. “I’ve seen the best and worst sides of human nature,” he states.

Money can, however, alleviate worry. A few months before his win, Rob and his wife, Robin, already parents of two boys, unexpectedly became guardians to Rob’s nephews. To prevent the youngest from being sent to a state facility, either Rob or Robin had to stay home. Robin quit her job. A few weeks later, what was destined to become a “credit-card Christmas” turned into “a very good one.”

When asked if he is happier now, Rob, who plans to return to nursing this year, is characteristically blunt: “If you weren’t happy before you win the lottery, then you definitely won’t be happy after.”

THE LOSERS

A good bankruptcy lawyer needs three things: a JD, a mind for math and boxes of Kleenex.

NOBODY ever really plans to end up in Ann Chapman’s office. But for 23 years, the bankruptcy attorney with VandenBos & Chapman has held the hands of—and supplied Kleenex tissues to—thousands of Portlanders who have been forced to declare legally that their wells have gone dry. More often than not, it’s a gut-wrenching process for those involved, but bankruptcy, she says, need not be a dirty word. “There’s this idea that people who file are liars and cheats,” she explains. “That’s not been my experience. At their hearts, people are inherently good and deserve a second chance.” Still, you’d probably rather not have a face-to-face with Chapman, one of the city’s top Chapter 13 experts. Herein, a dose of reality—and some straight-up advice—on how to avoid her office altogether and how to cope if you do find yourself there.

Image: Stuart Mullenberg

ON FINANCIAL ILLITERACY: We’ll ask clients to guess what they spend in a month on gas. They’ll say something like 100 bucks. But once you sit down with them and do the math, they’re stunned at how much it really costs. Life goes so fast. It never stops. Your wife gets pregnant. You have kids. Kids need daycare. And the expenses of the small business known as the American household keep growing.

ON THE TEARS OF MEN: I figure 80 percent of the people who come in cry in our first meeting. Grown men. Businessmen. That’s why we keep boxes of Kleenex in the conference room. If you can’t cry with your bankruptcy lawyer, who can you cry with?

ON HER DARKEST DAYS: I’ve probably had seven or eight clients commit suicide. They’re convinced there’s no way out, but it’s just money.

ON PEOPLE WHO OFTEN NEED HER: It’s the guys in their mid-20s to 30s. They’re working in shipping and receiving, making a $600-a-month car payment on some Ford Mustang chick magnet. They get laid off or sick, they get behind on their car payments and their car gets popped. Let me tell you: Buy the beat-up truck instead. It’ll get you there.

ON THE WORSHIP OF PLASTIC: Credit card companies have lulled us into this myth that they perpetuate: “Buy it. You deserve it. Pay the minimum and trust us. We want you paying us as long as you live.”

ON HELPING CLIENTS ACHIEVE ZEN: Bankruptcy lawyers are the helicopter above the forest fire, and sometimes we have to have hard conversations with people. Your business isn’t profitable? Your marriage is failing? Your health, too? Let us give you the big picture: Let it go. The forest is dying. Let it go.

ON THE BEAUTY OF THE FREE MARKET: Bankruptcy is the pressure-release valve of the capitalist system. What we’re doing is recycling entrepreneurs, reconfiguring them and making them smarter. They learn some hard lessons, but let’s not put them in a five-year financial prison.

ON HIGH DRAMA: What I do should be a TV series. There are so many compelling stories that come into our office. Tragedies, victories, shame, times when I’ve been truly touched by my clients. And it’s all real life. I’d call it Broke.

HOW WE SPEND IT

Three brave souls with income to spare expose where all their money goes.

PAM GRIMES

MOM/FREELANCE WRITER

HOUSEHOLD INCOME: $85,000

WHEN YOU SPEND your day ferrying around three kids attending three different schools and participating in three different activities (not to mention the trips to youth group and the grocery store), you need caffeine. As in a daily, heavy jolt of it. And fast food starts to look like an excellent dinner option. Pam Grimes, a freelance writer and full-time mom who lives in Tanasbourne, is the quintessential woman on the go (specifically in her white, Town & Country minivan); as such, she’s forced to make snap decisions about her spending en route to her next appointment and can’t get bogged down in the minutiae of her accounts. “My mother-in-law worked for a bank, and she’ll spend a whole afternoon balancing her bank account down to the penny. If I’m within $50, I’m pretty happy,” says Grimes, who recently added hot pink streaks to her hair “just to mess with” her teenaged son. Firm believers in charity, the Grimeses donate about $2,500 per year to a micro-lending program that funds small-business projects in Africa—and while major indulgences are few in her family, Grimes does like to drink great wine (chardonnay is her favorite) and wear great lingerie, even when she chooses not to bring home any bacon for dinner to fry up in a pan for her brood.

SPENDING DIARY

12/09/07-12/15/07

SUNDAY

$6 – 2 x venti americano, Starbucks

$57 – Christmas tree

$30 – Hamburger dinner for five, Burgerville

MONDAY

$6 – 2 x venti americano, Starbucks

$6 – Sandwich lunch, River City Saloon

$8 – School lunches

$30 – Groceries

TUESDAY

$3 – Venti americano, Starbucks

$9 – Chicken salad, Bugatti’s

$13 – Hair products, Victoria’s Secret

$175 – Charitable donation, Kiva

$17 – Photos with Santa

$49 – Hamburger dinner for five, Mark Lindsay’s Rock & Roll Café

WEDNESDAY

$6 – 2 x venti americano, Starbucks

$44 – Gas

$742 – Holiday gifts; Amazon, Target, Starbucks and Nike

$65 – Four pounds of cheese, Washington State University Creamery

$62 – Groceries

$7 – Dry cleaning

$30 – Guitar lesson for son

THURSDAY

$3 – Venti americano, Starbucks

FRIDAY

$3 – Venti americano, Starbucks

$99 – Groceries

$26 – Taco and burrito dinner for five, Chipotle

SATURDAY

$16 – 2 x venti americano and pastries, Starbucks

$84 – Computer class for son

$24 – Holiday gifts for family dog, Petco

$93 – Groceries

TOTAL

$1,713

BREAKDOWN

GROCERIES $316

CHARITY $175

DRY CLEANING $7

BEAUTY $13

GAS $44

STARBUCKS $43

CLASSES $114

EATING OUT $128

KEVIN COOK

EXECUTIVE ASSISTANT/FEMALE IMPERSONATOR

SALARY: $68,000

IN THE INTEREST of full-disclosure, we tapped one of our own, Kevin Cook, executive assistant to Portland Monthly’s publisher (who also has a second career as the drag queen diva known as Poison Waters), to expose his spending habits for one week. Cook affords his seemingly extravagant lifestyle of Broadway shows, cashmere scarves and martini lunches in part by keeping his expenditures very, very low: “I don’t have a wife, kids, a car or a mortgage,” he says. He often picks up tabs at meals with friends and donates about $5,000 per year to charity—generosity that’s partly a response to the generosity his own family received from others. “I grew up poor. We were on state assistance more times than not,” he says. Still, he admits to “overindulging” in some areas, namely size-12 (wide) high heels, ladies’ handbags and MAC makeup. “I have 20 years’ worth of evening gowns,” he says of the wardrobe that supports his nighttime profession. “But I always want more.” He refuses to comment on his low-grade addiction to video poker.

SPENDING DIARY

12/09/07 – 12/15/07

SUNDAY

$15 – Sausage and coffee with Bailey’s breakfast, JOQ’s

$40 – Video poker (won $181)

$40 – Charitable donations, Q Center

$60 – Cheeseburger lunch for five, Flying Pig

$100 – Video poker (won $263)

$20 – Drinks, Darcelle XV

$30 – Soup and salad late-night supper for two, Hobo’s

MONDAY

$13 – Fried rice lunch, Hunan’s

TUESDAY

$10 – Yoga

$7 – Soup and sandwich, Downtown Freddie Brown’s

$2 – MAX to PDX (to catch flight to New York City)

$2 – Bottled water

WEDNESDAY

(New York City)

$4 – Bottled water

$55 – Taxi to Carnegie Hall

$61 – Ticket to Broadway musical A Chorus Line

$60 – 3 x scarves, Gap

$2 – Hot dog lunch, street cart

$69 – Martini and croque madame lunch for two, Brasserie Maison

$20 – Charitable donation to Broadway Cares/ Equity Fights AIDS

$73 – Martini and “Italian” sushi dinner for two, Alfredo of Rome

$62 – Concert and cocktails, Zipper Factory

$9 – Mini-burger late-night supper, White Castle

$30 – Taxis

THURSDAY

(New York City)

$23 – Doughnut breakfast for two, Dunkin’ Donuts

$90 – 2 x tickets to Radio City Music Hall Christmas Spectacular Starring the Rockettes

$61 – Ticket to Broadway musical Curtains

$56 – Red wine and burger lunch for two, Roxy Delicatessen

$25 – 2 x Bailey’s and coffee, Al Hirschfeld Theatre

$26 – Taxis

FRIDAY

(New York City)

$9 – 2 x eggnog lattes, Starbucks

$10 – Photos, street vendor

$17 – 2 x shots of Bailey’s, Radio City Music Hall

$41 – Ticket to off-Broadway drama Die Mommie Die!

$207 – Cashmere scarf, Salvatore Ferragamo

$210 – Vest, sweaters, cuff links; Kenneth Cole

$183 – Scarf, sweaters, coat; H&M

$30 – Shoes, Rafik

$105 – Martini and salad dinner for two, Vynl

$44 – False eyelashes, nail polish, pimp hat; Ricky’s NYC

$20 – Martinis, New World Stages

$20 – Celia Cruz T-shirt

$143 – Appetizers and cocktails for two, Bar Ten Lounge

$65 – Taxis

SATURDAY

(New York City)

$13 – NYC T-shirts

$423 – 4 x beaded evening gowns; Elle Belle

$51 – Rhinestone accessories, Fashion Galaxy

$51 – Shirts, H&M

$55 – Soup and cocktails, Mercury Bar

$52 – Taxi to JFK airport

$40 – Taxi from PDX back home

TOTAL

$2,854

BREAKDOWN

MEN’S CLOTHING $774

ENTERTAINMENT/PARTYING $595

WOMEN’S CLOTHING $518

EATING OUT $471

TRANSPORTATION $270

GAMBLING $140

CHARITY $60

MISCELLANEOUS $26

HOLLY J CUNDIFF

PEOPLE SCOUT (PLEASE DON’T CALL HER A HEADHUNTER)

INCOME $99,999+

Image: Stuart Mullenberg

ONCE A WEEK, a bookkeeper arrives at the office of small-business owner Holly Cundiff, ferries away all of the receipts she’s accumulated over the past seven days, updates her taxes and pays the majority of her bills. The weekly assistance turns out to be a smart management tool for someone who prefers not to think about money. She can’t remember the last time she owned a credit card: “They kept charging me interest. I didn’t like it,” she states. For Cundiff, who lives with her fiancé in Northeast Portland, money is often a means to a holistic brand of hedonism, one that consists of weekly rituals that combine relaxation and indulgence. Every Tuesday, for instance, she sits in the dry sauna at Löyly and follows it with a solo dinner at Vindalho, where she orders the same beautiful meal (beet salad, samosas, saag paneer and a glass of Rhone Valley red). Her friends, too, have benefited from Cundiff’s approach to life: Consider the 20-dish Russian meal she had catered to celebrate Thanksgiving, or the party she simply called Spain, which featured a suckling pig roasted golden, an apple stuffed gloriously into its mouth. When ordering wine, she typically does not look at the price, preferring to tell the sommelier to bring her “a fat wine that never has to say, ‘I’m sorry.’” The sommeliers, she says, “are very good about it.”

SPENDING DIARY

12/02/07 – 12/08/07

SUNDAY

$2 – Oregonian

$68 – Japanese tea, beer, snacks and six lucky cat statues, Anzen

MONDAY

$6 – 3 x bottled water

$5 – Falafel and tabouleh lunch, street cart

$218 – Groceries and herbal supplements

$250 – Haircut and color, David Kennedy

TUESDAY

$3 – Yerba maté tea

$30 – Allum leaf (for combating the aging effects of particulate matter)

$6 – Metzo plate, street cart

$40 – Douglas Sirk DVD, All that Heaven Allows

$5 – Street Roots newspaper

$143 – Massage, sauna, masks, creams; Löyly

$12 – 3 x bottled water

$7 – 2 x bottled Guinness

$45 – Wine and saag paneer masala dinner, Vindalho

$6 – Pack of clove cigarettes

WEDNESDAY

$3 – Apple and yerba maté tea

$12 – Tabouleh lunch, street cart

$149 – Knee-high Liberace boots, Spartacus

THURSDAY

$30 – Taxi to PDX (to catch flight to New Mexico with mom)

$5 – Portland Monthly

$6 – 3 x bottled sparkling water

$23 – Egg breakfast for two, PDX

$12 – 3 x Sobe tea

$3 – Double espresso

$149 – Prime rib and Veuve Clicquot dinner for two, Cristobal’s (Santa Fe)

FRIDAY

(Santa Fe, New Mexico)

$11 – Coffee and water, Starbucks

$15 – Merle Haggard CD

$234 – Salt scrub and Navajo hot-oil scalp rub, Downtown Day Spa

$18 – Tamale lunch, Hot Tamales

$80 – Bottle of zinfandel, Café Pasqual

$25 – 2 x shots of Maker’s Mark, sparkling water, Hotel St Francis

SATURDAY

(Santa Fe, New Mexico)

$310 – 2 x nights at Hotel St Francis

$5 – Sparkling water

$135 – Round of golf, Pueblo de Conchiti

$20 – Omelet lunch, Pueblo de Conchiti

$38 – Swedish-style hat

$47 - Books by Kant, Hegel, Aristotle

$12 – Double Maker’s Mark, Hotel St Francis

$144 – Rental car

$28 – Gas

TOTAL

$2,360

IF YOU’VE GOT IT, FLAUNT IT. Not exactly the most fitting motto for Portland. But there are those among us for whom price really doesn’t matter. Coffeemakers that cost as much as used cars? Check. Personal jets worth the GNP of small African countries? Sure. Heated floors for your goats? Oh yeah. Whether you’re window-shopping or living vicariously, these mega-priced items, all of which were sold (or put up for sale) in the Portland Metro area in 2007, are an eye-popping reminder: This is how the super-rich really live.

JURA – CAPRESSO IMPRESSA Z6 SUPER AUTOMATIC COFFEE CENTER $4,500

IT SOUNDS LIKE it should have a spoiler and racing stripes, but the Z6 sold by Sur La Table is, in fact, just an espresso machine. But unlike your rickety Mr. Coffee, this creation—part percolator, part supercomputer—requires you to sit through a 35-minute-long DVD tutorial before you can strap yourself inside its chrome-caffeine embrace. “It’s very high-tech,” says a Sur La Table part-time counter girl, who would need to save her salary for four months to buy one. “But once you master the pre-programs and settings, all you have to do is punch a button.” What better way to stick it to the dead-eyed barista than to render him obsolete?

FAIR-TRADE RUBY $35,000

LONG BEFORE Leonardo DiCaprio’s bad Zimbabwean accent in Blood Diamond hurt the ears of moviegoers everywhere, Eric Braunwart was banging the fair-trade drum in the gem industry. Braunwart, the owner and CEO of Columbia Gem House, a wholesaler in Vancouver, had long stopped buying rocks from areas where miners endured sub-standard working conditions or were caught in third-world power struggles. Today he’s able to specialize almost exclusively in conflict-free gems—even though that kind of certification usually comes with a 30 percent price mark-up for the customer. “At the end of the day we’re selling a luxury item,” Braunwart says. “But people don’t mind paying a little more to be part of the movement.” As evidenced by this crimson 3.25-carat ruby from Malawi that has all the subtlety of a shiny red apple dangling from your finger.

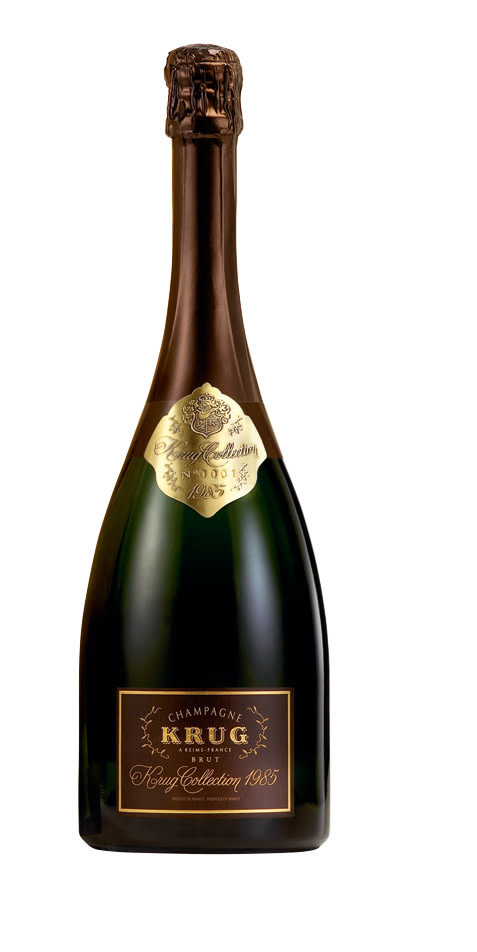

KRUG COLLECTION 1985 CHAMPAGNE $700

TASTY ENOUGH for even the most fickle of tongues, regal enough for christening an ocean liner, the 1985 cellar offering from the legendary Krug Collection circulates like liquid gold among wine snobs. These deep green bottles have lain undisturbed in the cool, cavernous crypts of the Krug estate in France developing a wave of flavors: an initial hit of toasted brioche, vanilla and caramel, followed by dried fruit, honey and coffee. Of course, the longer this ages, the more the flavors will morph. Some sippers have even tasted truffles. Want to hunt down a bottle? Ed Paladino over at E&R Wine Shop can cut you a sweet deal: a mere $700. “It’s a lot of money,” he admits, “but it’s a really amazing champagne.”

GULFSTREAM 550 $50,000,000

SELLING PRIVATE AIRPLANES in this high-flying decade has become a lucrative business in Portland—how else to explain the need for seven local aircraft dealers? But one plane soars above the rest: the Gulfstream 550, a leather-lined, jet-fueled sky-loft considered the Lamborghini of private aviation. So what’s driving the demand? “Have you flown commercial lately?” offers Robert Baugniet, with Gulfstream’s communication office in Savannah, Georgia. Should you feel similarly exasperated by mile-long security lines, $50 million will buy you access to phone, fax, internet, satellite communications, beds, kitchen and an endless supply of fresh, non-recycled air. Even billionaires must have patience, though. Order now and your plane might be ready by 2012.

VANILLA BICYCLES CUSTOM-FIT ROAD BIKE $5,000+

THERE ARE BICYCLES and then there are the chrome-and-gear works of art that Sacha White handcrafts at Vanilla Bicycles. Polished lugs. Custom racks. High-tech steel alloy frames built to fit your exact measurements. Think of it as West Coast Choppers for the non-motorized set. And it will set you back, on average, $5,000 or more. In fact, it’ll be $500 to $1,000 down just to get a spot in line. And right now, that line is closed. “We’re building bikes five years out right now,” says White’s assistant, Scott Ramsey. “Some people are pretty disappointed when they hear that.” And no, Vanilla does not accept bribes.

MANSION IN SHERWOOD

Image: Lee Bonifiglio

PORTLAND MAY BE quintessentially cute, what with its abundance of moss-laden bungalows, but its upper echelons still show a preference for homes more aptly described as manors. Consider this presently uninhabited 9,538-square-foot monstrosity for sale in Sherwood. Constructed in the Italian Renaissance style in 1999, and erected on 20 ornately landscaped acres that appear to have been air-lifted straight from Florence, the fabulous suburban villa represented by Harnish Properties at Realty Trust includes a granite cobblestone driveway, a domed entryway hand-painted with fields of Tuscan sunflowers, and ponds for turtles and koi. Plus, the goat barn has heated floors. Yes, the goat barn. Because when you’re this loaded, even the horned menace that ate your Bruno Maglis shouldn’t have to suffer chafed hooves.

THE ANTI-CONSUMERS

One family says enough is enough.

Image: Stuart Mullenberg

THE MILLERS

Tim, Kym, Laugan, Sage & Jenna

IN JANUARY 2007, the scientific journal Neuron offered an explanation for why some people obsessively fill their lives with stuff. Apparently these super-consumers—of which I am one—have an overactive nucleus accumbens, that part of our brains commonly known as “the pleasure center.” Covered with receptors that attract dopamine—a hormone and neurotransmitter that imparts feelings of bliss—the nucleus accumbens can go into overdrive in response to certain stimuli. Why that is, science cannot precisely explain.

For me, once upon a time, that stimuli could have been something as simple as the shiny glaze of a midnight-blue flowerpot that I just had to have for our deck. A pair of black leather boots with stiletto heels slightly taller than those of the three pairs I already owned could compel me to whip out my credit card with nary a hint of trepidation. In fact, by the early 2000s, I had become such a successful consumer that our family joined the nearly one out of every 10 households in America that funneled their material overflow into a rented storage unit. My nucleus accumbens, I now know, was largely responsible for making me feel positively giddy at the prospect of buying and owning that perfect thing. Which, it turns out, I never actually found.

What the Neuron article did not address is whether anything could be done about this compulsion. In 2003, I endeavored to take the matter into my own hands. And while my solution—a wild family experiment of anti-consumption that lasted for an entire year—would not likely hold up to the rigors of scientific testing, I can report that it is possible, if not to reprogram the nucleus accumbens entirely, then to at least calm it down.

The night I tried to convince my family of the merits of my “Year Without Buying” plan, in which we would purchase only edible items for a solid 12 months, did not go well. My husband, Tim, remained silent, my pre-teen, Jenna, just looked stunned and 4-year-old Laugan continued playing with her dinner. Only our middle daughter, Sage, was fully in my camp. “Think how much we would save!” she exclaimed. But I was quick to point out that the experiment was not so much about saving money as about discovering what would happen to our psyches if we reined in our desire for objects altogether.

After Tim noted that lightbulbs would be hard to live without, we entered into a month-long negotiation period, during which we debated which among the non-edible items were absolutely necessary to buy. Deemed “depletables,” these included such things as batteries, shampoo, soap, toothpaste, deodorant and medicine—anything that could be used up completely. We agreed that services—such as travel, house-cleaning and repairs—were allowed, but if something actually broke completely, we couldn’t replace it.

Assembled around the dinner table on Friday, January 31, 2003, I initiated a vote: Would we or wouldn’t we commit? Trying to sound confident, I voted “yes.” Next came Sage with a resounding “yes” and Tim, who delivered a more hesitant “yes.” Jenna, taking a brief glance around the room as if to say goodbye to all that was dear to her, concurred with even less enthusiasm, and finally Laugan gave her approval—but only after we assured her that candy was part of the “edible” category.

Our experiment began the next day, and within a few weeks, because we could no longer run out for a new plunger, the latest Sting CD or even a pair of socks, Tim and I noticed that we were taking fewer trips to the gas station. We also discovered our hidden fix-it abilities, which we applied to a broken DVD player (we only needed to clean the lens cover), a busted birdhouse that just needed a few nails, a ceramic bowl (which we painstakingly reassembled with superglue) and numerous other items that previously would have been dumped in the trash. Why had we been spending our hard-earned cash to replace these things when it was actually fun to fix them?

Holidays, such as Easter, were transformed into creative occasions. In our zeal to acquire store-bought seasonal kitsch, we’d failed to notice that we had a lawn full of real grass that was just as suitable a basket-filler as the shiny plastic kind. And for Easter goodies, we’d overlooked a box of beads easily transformed into necklaces, decks of playing cards we found in old crates and half-empty bottles of bubbles. For Christmas, however, the biggest consumer holiday of all, refurbished trinkets would not suffice. With this in mind, I began to tuck away extra items that came our way, such as books passed on by friends. I rescued two tennis rackets from the storage unit and found an unused game of Operation in a forgotten corner of the attic. I helped my friend clean out her house and scored a wealth of items her daughter no longer wanted, including a slightly used cell phone. On Christmas morning Jenna—phone in hand—whispered to us, “How did this happen?” and each child seemed unusually grateful for all that lay before her.

Not every moment was imbued with the enlightened feelings of personal betterment: Each of us at some point endured bouts of suffering. Consider vacuum bags, which were disposable but not depletable, forcing me to repeatedly empty and re-staple the one we had. When the kids came down with colds, a vaporizer would have eased their pain. Alas, we didn’t own one, so we placed a decorative water fountain in their room to moisten the air.

Nor did living out this idea restrain me from conjuring up new schemes along the way. Enraptured by our minimalism, in August I suggested we have a garage sale. “And sell what?” my exasperated husband asked after a dumbfounded pause.

“Well, we have clothes we don’t wear, toys we don’t play with and CD’s we never listen to,” I said. “Why do we need 30 screwdrivers and 6 hammers?” We earned a few bucks at the sale, but more importantly, we experienced a satisfying amount of de-cluttering and community bonding. A grateful Goodwill employee even collected the leftovers.

Word of our experiment elicited a spectrum of reactions from friends, some of whom decided to try something similar. My parents, on the other hand, wondered out loud if we had become destitute—why else would we voluntarily suffer so? Most shocking were those who perceived our experiment as an assault on America itself. One friend even said, with utter seriousness, “This could single-handedly bring down the economy!” Is it really the responsibility of a middle-class family to spend in excess, and how and when exactly did this expectation of consumption become a patriotic imperative? In December, we celebrated the year’s end with a week in Maui. Our feasting, snorkeling and exploring ate up most of our savings, but we felt we did our part to buoy the 2003 economy.

On January 31, 2004, our experiment came to a close. It took us almost three months to buy anything new again. We had simply gotten out of the habit. Our first purchase was a pair of dress socks for Tim.

When people ask me what we learned, I always wonder where to begin. Do I talk about the unexpected feelings of freedom? Our newly acquired repair skills? The seemingly effortless and generous flow of used items that came—and continue to come—our way, or our deeper connection with those around us?

Recently I read a newspaper article that reported, “Black Friday turned into black-and-blue Friday at the Boise Towne Square mall.” The lure of bountiful bargains at an Idaho shopping center had drawn thousands of people to wait in the cold on Thanksgiving Day for a scheduled 1 a.m. opening. When the mall entrance was unlocked, chaos ensued. The crowd knocked a glass door from its frame, and the stampede resulted in several injuries requiring assistance by paramedics. It’s hard for me to accept that such behavior is the result of brain chemistry alone.

One thing the year did not cure, however, was my pursuit of ever more novel ways to improve my family’s lives. About a year ago, I began to feel that we five were over-scheduled and that we spent our days madly rushing from one activity to the next without the chance to truly appreciate the present. “Where is that magical valley of existence called ‘the Now?’” I wondered. And then I had a crazy idea… —KCM