The Rose Defense

CAROL VAN STRUM stood on the steps of the Marion County Courthouse, one hand shielding the sunlight from her eyes, straining to catch sight of the man who had agreed to try to save her son. With so many lawyers streaming in and out of the building—men and women in tailored suits, cell phones pressed to their ears—it was turning out to be a difficult task.

So it helped when Michael Rose announced his arrival not with a firm handshake or the presentation of a business card, but with a commotion. One that sounded like a million asthmatics hocking up a lung.

It was the death rattle of his prized relic, a 1989 Mazda sedan badly in need of repair. Not exactly the kind of chariot Van Strum had expected from someone whose name graces the Portland law firm Steenson, Schumann, Tewksbury, Creighton and Rose. Nor was his garb what she’d anticipated: a cream-colored jacket that appeared yellow in the sunlight and a psychedelic, Jerry Garcia-brand tie dangling from his neck.

“You could probably have spotted that tie from a satellite,” says Van Strum of Rose’s grand entrance that day in March 2007. “It was hard to keep a straight face.”

But if Van Strum was laughing, she quickly hid her mirth in Rose’s shoulder, eschewing formality in favor of a crushing hug. The two had met before, briefly, but today the stakes were high. This man with a tousled Brillo pad of hair and a sandy red mustache—a man whose name inmates often had summoned in the darkest, most hopeless confines of the Oregon State Penitentiary—had promised to achieve what seemed impossible: overturn her son’s murder conviction.

Rose had filed a motion for the most elusive of appeals, what is termed in legal parlance “post-conviction relief,” a kind of last-chance law that allows defendants to challenge a guilty verdict—but only after exhausting every other appeal. Van Strum’s adopted son, Jordan Scott Merrell, already had spent nine years behind bars. Today Judge Terry Leggert finally would reconsider his case. If Leggert ruled in Rose’s favor, Merrell would not be set free, but he would be granted a new day in court and the chance to plead his case in front of another jury—as if the original trial had never taken place.

In 1998, Merrell was convicted of the grisly murder of an elderly man in Eugene. At the time of the killing, the youth had not yet celebrated his 16th birthday, and his case was one of the first to test the uncompromising teeth of Measure 11, a controversial initiative passed by Oregon voters in 1994 that not only established mandatory minimum sentences for a range of serious crimes, but also required offenders over the age of 15 to be tried as adults. Merrell pled not guilty to the charges, but after a court case that lasted only a few days, the jury delivered a guilty verdict. He was sentenced to 25 years. No time off for good behavior. No chance for parole.

Yes, he’d confessed to the murder during the original investigation. But Merrell later said that he’d done so only to cover for a friend and that he was not, in fact, the killer. His fellow inmates told him that there was one man he should contact for help: attorney Michael Rose.

Merrell’s case file arrived at Rose’s office in 2001. When he began to peruse the documents—in spite of the confession—Rose saw a post-conviction case that he might be able to win. “If you’re a creative kind of fella, you look at that confession as a challenge,” he says, arching one fuzzy eyebrow. “You have a confession? OK. So the question is: Why isn’t this confession the end of the story?”

At the time that Merrell contacted him, Rose had been working for 26 years as, at various times, a public defender, an indigent defender, and an attorney in private practice. Last-chance appeals like Merrell’s, which Rose only sometimes gets paid for, had become more of a personal crusade. He’d litigated some 150 post-conviction relief cases, but took only about half of the cases brought to him.

The ones he did sign on for were often doozies: In 1995 he had John Sosnovske’s murder conviction overturned and helped pin the crime on the rightful assailant, Keith Hunter Jesperson, known as the Happy Face Killer. But unlike that case—in which Sosnovske pled no contest to a murder that his girlfriend had convinced him he’d committed—Merrell’s case rested on the notion that his original court-appointed attorney, John Halpern, had failed to perform due diligence on his client’s behalf. Rose’s job was to ask: Had Merrell received a fair trial? More specifically, had Merrell’s constitutionally guaranteed right to the “effective assistance of counsel” been fulfilled? Rose was prepared to tell the State of Oregon, emphatically, “No.”

Rose and the private investigator he hired, Stuart Steinberg, spent roughly five years collecting evidence, and on the day that Rose met Van Strum down in Salem, most of that evidence was packed into the trunk of his sedan: box after box of three-inch-thick binders full of affidavits, psychological evaluations, and alibi testimony, none of which Merrell had had access to during his first trial. In fact, Rose and Steinberg had uncovered so much new information on the Merrell case that Rose had to wheel it into the courtroom on a hand truck.

“The reaction from the gallery,” he recalls, “was something like, ‘Oh, shit.’”

It’s late April in Eugene, but a rejuvenating break in the weather offers a sneak peak of summer’s impending beauty. No clouds. The welcoming char of the sun. Up here near the top of College Hill, the smells of fresh-cut grass and spring onions mingle in the breeze, mowers wheeze in the distance, and you can see a clan of Little Leaguers gathering for practice in a baseball field.

It feels safe in this tiny encampment of bungalows. But 11 years ago, during the summer of 1997, this entire southwest Eugene neighborhood was a crime scene. Pieces of a murder weapon left in one yard. A knit cap tossed in the shrubbery of another. And just down the hill, inside a beige brick house that now has two pairs of galoshes drying on the front porch, there was a body. It was here, on the Fourth of July, that 83-year-old Edward Bonci was bludgeoned to death with a cane.

At the time of his death, Bonci was frail and in the early stages of Alzheimer’s. The yellow bruises on his body testified to a history of falling. But when his son, Scott Bonci, found him the morning after his death, there was blood everywhere: In the living room. Pooled in the kitchen. At first, police weren’t sure what to make of the scene. Three days later, though, what had warranted only a passing blurb in the City/Region Digest of the Register-Guard—“Police investigating death of man, 83”—rocketed to a three-deck headline on page 1A: “Three Youths Arrested After Beating Death.”

Justin Gottfried, Jordan Merrell, and Meryl Colborn, the three acquaintances in custody, all were estranged from their families at the time and, for the most part, were living on the streets. Colborn was the victim’s adopted granddaughter and a frequent visitor to Bonci’s home; because of numerous past altercations with her grandfather, she was a suspect from the beginning.

According to police reports, the youths had snuck into Bonci’s house during the afternoon to steal money. Bonci was lying on the floor watching television, but apparently put up a struggle when they tried to take his wallet from him. That’s when somebody used a cane to fracture his skull.

The trio got away with $87, enough to buy a bag of marijuana and snacks at a local Circle K. Within two days, police picked them up on the Eugene Mall, a public space in downtown Eugene where kids, junkies, and heshers often hung out.

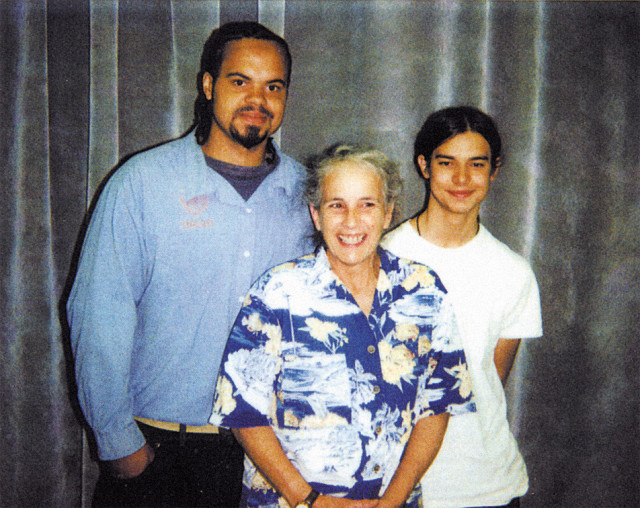

Image: Carol Van Strum

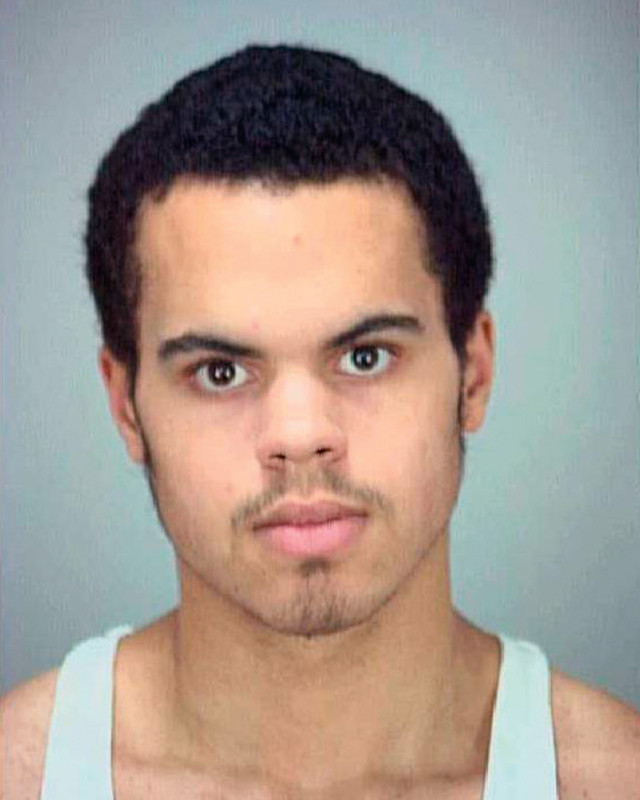

The crime was gruesome. But perhaps more disturbing, the suspects were just young teenagers. Gottfried and Colborn were both 14, and they looked it, even in the mug shots printed in the newspaper. Merrell was only a year older, but at 6-foot-2 and 200 pounds, he towered over most kids his age. Eugene detective Rick Gilliam, one of the investigators on the case, was quoted in the paper as saying that “just [Merrell] alone could have handled this victim very easily.”

On July 17, 1997, a grand jury indicted Merrell on charges of felony murder, as well as robbery and burglary. Colborn and Gottfried were tried as juveniles and eventually sentenced to 17 and 11 years respectively. Merrell, on the other hand, was prosecuted under Measure 11, making him one of the first Oregonians under age 16 to face the automatic 25-year sentence.

While the prosecution lacked the physical evidence to prove that Merrell was the one who killed Bonci, it had something even more damning: a confession. Soon after his trial started on February 19, 1998, the jury listened to the tape-recorded statement in which Merrell told police that the three had joked about the sound the cane made as Bonci’s skull caved in.

All told, the prosecution, led by Assistant District Attorney Caren Tracy, delivered 332 pages of “discovery” evidence and numerous witnesses, ranging from the state’s deputy medical examiner to Merrell’s ex-girlfriend, to the court.

Halpern’s defense, on the other hand, conceded that while Merrell may have struck Bonci, the relatively low amount of blood in the living room, where the attack occurred, meant the blow itself didn’t actually kill the man. Halpern’s lone witness, a Portland-based pathologist with no expertise in blood spatter patterns (and with only the state’s evidence on which to base his opinion), testified by phone. It took the jury less than an hour to convict Merrell.

Of course, the jury never heard about the well-known unreliability of juvenile confessions, or the pattern of aggression that Colborn had displayed toward her grandfather. They certainly didn’t know that on the day that Bonci was murdered, a witness—who was sitting in the courtroom during the the trial—placed Merrell three miles away. How could they? Halpern never mentioned these points in court.

“I wrote in a brief a long time ago that sometimes all it takes to meet the standard of adequate assistance of counsel is a license, a clean suit, and sober breath … and two out of three is usually enough,” Rose says. “Good attorneys have bad days—but unfortunately this bad day wound up coinciding with the trial of my poor client.”

Carol Van Strum can’t say exactly when initial misgivings about her son’s public defender turned into outright, helpless horror. Perhaps it was when she sat down to write the 23rd letter to Halpern begging him to visit her son in the Lane County Jail, where Merrell was being held before the trial. Or maybe it was the 39th. Between July 15, 1997, and February 25, 1998, Van Strum sent her son’s attorney 41 letters and faxes asking for updates or information about the impending trial. Only rarely did she receive a reply.

Panicked, Van Strum called a lawyer friend who lived in California. “He said the thing to do was to get the police report and go through it line by line and put in writing every contradiction I found—everything that pointed away from Jordan or suggested he wasn’t there,” Van Strum says. “That’s what I did.”

Underlining. Highlighting. Looking for anything that might pass for reasonable doubt. What Van Strum, a freelance writer and $8-an-hour bookstore employee, found on page 245 of the police report—what Halpern, a criminal defense lawyer with degrees from Dartmouth College, Columbia University, and the University of California-Berkeley, had failed to notice—was evidence suggesting that Merrell might not have been present during the crime at all.

Image: Carol Van Strum

In Merrell’s confession, he stated that he struck Bonci in the late afternoon or early evening, “probably 6:30 [p.m.] at the earliest.” But at the original trial, the time of death was established as sometime prior to 2 p.m. This timeline was pieced together from the testimony of Colborn—who told police that she, Merrell, and Gottfried first went to Bonci’s house at around 11 a.m. and then again around noon, when they robbed and killed him—and that of a neighbor, Rex Prater, who told police he found a portion of the cane allegedly used in the attack in his yard at approximately 2 p.m.

This discrepancy was never brought up by Halpern at trial, even though Van Strum claims she pointed it out to him at least two months before the proceedings began. Nor was the fact that during the established time frame of the crime, Merrell could have been somewhere else. In interviews with the police seven days after the crime—and in a sworn affidavit taken nearly 10 years later—Elisa Olalde, then a friend of Merrell’s, says he was at her house from “sometime before I woke up at 8:30 a.m. until approximately 12:30 p.m.” All of this information was in the police report.

Halpern refused to talk about his defense strategy when contacted for this story. Richard Hursey, the investigator hired by Halpern to track and interview witnesses, didn’t return calls seeking comment. But Patricia Jaqua, Halpern’s other investigator, concedes that “I’m not real surprised they went for a retrial.”

There was also the fact that Colborn had a history of taking advantage of her grandfather’s dementia to talk him out of money. Things got so bad at one point that Bonci’s son (and Colborn’s adoptive father), Scott, taped a sign to the inside of his father’s door—a warning for Bonci’s Meals-on-Wheels volunteer that read, “If Meryl comes to the door, don’t open it. Call 911.”

Just before the murder, Colborn had escaped from a court-ordered stay at Meadowlark Manor in Bend, a treatment facility for juveniles. Peggy Kastverg, who was Meadowlark’s director at the time, told Rose’s investigator, Stuart Steinberg, that Colborn had threatened to kill a staff member. In Steinberg’s report, Kastverg described her as “a real criminal kid.”

Merrell told Steinberg that he confessed partly to protect Colborn from being convicted. “[She] was younger than I was, and I perceived her as being vulnerable and in need of protection,” he said. In fact, Merrell’s half brother, Zack, who lived in Eugene at the time, says he saw Merrell shortly after the murder. Merrell told him that “Meryl was in real bad trouble” and that he’d decided he “would take the blame.” According to Van Strum, Merrell thought that even if he actually were convicted, he’d just serve some time in a juvenile facility and still be able to finish high school.

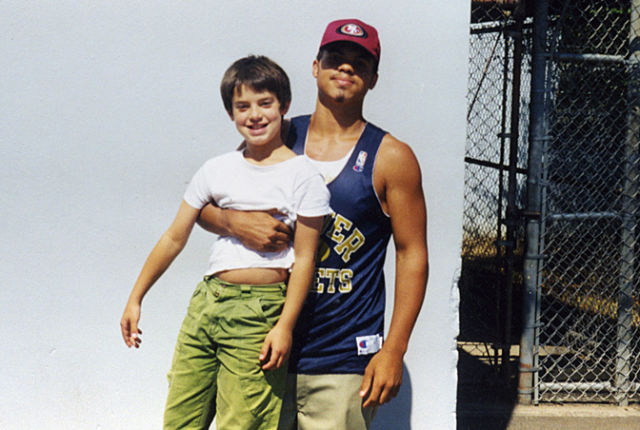

Image: Stuart Mullenberg

“The usual rules don’t apply with teenagers,” says Rose of juvenile confessions. “Black is white. Confessions are not confessions. There’s an element of fantasy involved, wanting to seem big. You have to take everything with a grain of salt.” The numbers back him up. In a 2005 nationwide analysis of 340 overturned convictions between 1989 and 2003, Professor Samuel R. Gross of the University of Michigan Law School found that 42 percent of exonerated individuals who had confessed to serious crimes they did not commit were under 18 years old at the time of their confession, and 69 percent of those were 15 or younger.

After the verdict on March 9, perhaps to console a mother who had just seen her child shipped off the MacLaren Youth Correctional Facility, Halpern told Van Strum that Merrell would have a strong case for “post-conviction relief.”

But since so much of the mitigating information—the alibis, Colborn’s history, the problematic confession—was not entered into evidence during the first trial, it couldn’t be used as a basis for appeal. Not until every possible review from the original trial was exhausted, that is. Somebody could get Merrell a retrial. But it wouldn’t be Halpern.

To get to Carol Van Strum’s house, you have to follow a sign to Fisher, a town that hasn’t existed in 60 years. Take a left turn over the Alsea River and drive through 10 miles of thick flora to the edge of the Siuslaw National Forest, just 30 miles from the coast. Her instructions for finding the muddy, tire-tracked path to her home require visitors to use mile markers as guidance, since there’s little to distinguish a makeshift driveway from a gravel road to Deliverance-ville. It’s about as far off the grid as one can live and still be able to check e-mail.

Image: Stuart Mullenberg

This is where Van Strum has lived since 1974. On New Year’s Eve 1977, her house burned down, killing four of her children, aged 5 to 13, from her previous marriage. They’re all buried on the property, out back near the apple trees. After the tragedy, Van Strum didn’t have the money to rebuild, so she made a home from what was left amid the ashes: The garage became the living room; a second story was constructed on top of it; and a bedroom was built on the side for Jordan, who was adopted on the day of his birth in 1981, and his brother, Nikko, who is the biological son of Van Strum and her ex-husband, Paul Merrell.

Now even those additions have fallen into disrepair. The staircase is boarded up, and Jordan’s old bedroom has a blue blanket nailed over the doorway. The room’s roof has collapsed, and a Star Wars poster and stuffed Keiko doll are the only remaining evidence of the children who used to live here. If you need to use the bathroom, you have to trek to the outhouse. Or the nearest bush.

This is where Jordan grew up. There are pictures of him near the computer; he’s dressed in prison blues, hair usually woven into tight rows, looking hard. On the inside they call the 26-year-old “The Professor” for his propensity for reading—everything from Tintin to books by physicist Richard Feynman. And while a few photos on the wall attest to happier times, a darkness seems to have followed Jordan Merrell since the day he was born.

In an affidavit from his biological grandmother, Jordan’s birth mother is described as mentally ill; his real father has never been found. Because of his mixed race—one of his parents was African American and the other was white—Merrell was exposed to incidents of racism. According to Van Strum, he was one of only two nonwhite kids at Waldport Middle School, and at basketball games, people in the crowds would say things like, “Kill the nigger.” His adoptive father, Paul Merrell, was abusive. “It was bad,” Van Strum says. “That’s why we split up.”

But it wasn’t just the kicking and punching. Paul spent over two years in Vietnam as a psychological operations specialist with the 5th Special Forces Group, and Steinberg’s report notes that after returning home, he was considered to be 100 percent disabled by Veterans Affairs, which cited diagnoses of schizophrenia and post-traumatic stress disorder, among other afflictions.

In a memo that she kept for herself detailing Paul Merrell’s abuse, Van Strum described one particular incident: “To punish Jordan…Paul keeps him up almost all night, forcing him to sit in a chair without moving, making him do push-ups every time he moves a finger or starts falling asleep…Paul holds Jordan’s Walkman in Jordan’s face and systematically rips it apart and smashes it beyond repair, then threatens to do the same to Jordan, pulls off his vest to do so, starts to go for him until I pick up a fire poker.”

On January 13, 1995, at the age of 13, Jordan tried to kill himself with an overdose of aspirin and ibuprofen.

It was the beginning of a downward spiral for the teen. In February 1995, after Van Strum and Paul Merrell had separated, the Lincoln County Circuit Court issued a domestic violence restraining order against Paul. Four months later, Jordan was popped for spray-painting gang-related graffiti (“OGJSM,” which stood for Original Gangster Jordan Scott Merrell) on a wall at Waldport Middle School. He was charged with criminal mischief and placed in the Lincoln County Shelter Home, a juvenile facility. He told therapists he’d been dabbling in pot since the age of 6, hallucinogens since the age of 7, and alcohol since the age of 10.

Steinberg’s investigation shows that numerous counselors documented Jordan’s deteriorating mental state. He was described at various points between 1995 and 1997 as being “self-destructive,” “depressive,” “at-risk.” One psychologist described him as “dysphoric,” an agitated state often associated with depression, psychosis, and thoughts of suicide.

Partly as a result of the graffiti incident, Jordan was accepted at Bob Belloni Ranch—a juvenile treatment center in Coos Bay—but when asked to sign a consent form, Paul Merrell opposed the treatment plan.

According to a report from Skipworth Juvenile Facility, where Jordan was taken after his arrest for Bonci’s murder, Jordan complained about “spiders coming through the cracks in the wall.” At one point he drew a cross on the wall of his room with his own blood. He was placed on suicide watch.

Despite all of this, Halpern never had Jordan psychologically evaluated for the trial. Nor did he conduct the kind of investigation that might have led him to build a defense around Jordan’s mental state—although he did file a notice of intent to do just that in August 1997. However, he withdrew the notice in January 1998.

Image: Stuart Mullenberg

During Jordan’s confession to police, Detective Scott McKee asked him, “And so when you guys came in there, into the room—what was your plan?” In response, Jordan stated, “Like if this was my dad, I thought about my dad a lot and…so we just went…and did what we did.”

For Merrell’s post-conviction relief hearing, the monsoon of evidence that Rose and Steinberg had uncovered highlighted what Rose, in a memo to the Marion County Circuit Court, called the “thorough failure” of Halpern’s defense. On December 13, 2007, nine months after the hearing, the state signed the petition that granted Merrell the post-conviction relief he sought. The concession speech from Assistant Attorney General Susan Gerber was simple and to the point: “You win.”

Merrell would be assigned a new defense lawyer, who would conduct a new trial, as if the first trial had never occurred.

“In this case we found that the defendant did not have effective counsel,” says Stephanie Soden, a spokesperson for the Department of Justice. “It’s a fairly common reason to petition for post-conviction relief, but it’s one that’s rarely granted. Then again, Michael Rose has a very good reputation.”

Van Strum received the news on her 67th birthday. She said it was the best present she had ever received.

Nevertheless, for the parties involved in the case, there are no happy endings. After all, Scott Bonci lost his father that day in July. “I’m not into retribution,” Scott says. “But I’ve sat through a reenactment of the crime [which was part of Colborn’s court-ordered treatment]. It would really bother me if Jordan said that he wasn’t involved.”

And in the end, Merrell wasn’t sure he could convince a jury that he wasn’t. His new trial was scheduled to begin this month, on June 10. But in early May, he agreed to plead guilty to Edward Bonci’s murder in exchange for a reduced sentence. “There’s a big difference between being granted post-conviction relief and proving that somebody is innocent,” says John Kolego, Merrell’s new attorney. “What Rose did was get the guy a new trial. But there’s always a risk associated with that.”

The plea did, however, reduce the number of years that Merrell must stay in jail—from 14 to 7. “I feel like I’m right there, about to get out, compared to how I was feeling with 14 years left,” Merrell wrote in a letter to his mother. “I assure you I didn’t do what I confessed…But it’s time to move on.”