The Shape We're In

Photo: iStockphoto image #000017439420

LIKE EVERY CITY, Portland has its own power mythology. Our Lilliputian metropolis might never spawn giants like Chicago’s Mayor Daley or New York’s Robert Moses, but we’ve had no shortage of old-school male mahatmas hammering out deals in smoke-filled rooms. As one longtime scholar of the city puts it: “Back in the old days, maybe 10 people really got stuff done. They fit around a table at the Arlington Club.”

Glenn Jackson, the ’60s energy and highway czar, could basically point his finger and make a six-lane bridge arise, or the Harbor Drive highway go away. Neil Goldschmidt, the mayor–turned–power broker–turned–Shakespearean tragedy, reshaped downtown and built light rail before sex abuse revelations sent him to the political glue factory in 2004. The key question of local power once yielded definite answers.

For the past few months, we’ve queried pols, pundits, activists, and insiders past and present in an effort to answer the question: just who does run this place, anyway? In The 50 Most Influential Portlanders, you’ll find one result: our eclectic selection of 50 people and groups likely to shape Portland in the years to come.

But we also discovered an almost unanimous belief that today nobody runs Portland. The city and the world have grown too complex (and today’s bigwigs too weak) for any one person or group of insiders to tug the reins. We’ve become a city with no center. Sometimes, the results can be, as the protesters say, what democracy looks like. As one prominent politician observed: “A power structure evolved around Goldschmidt in the ’70s. For better or worse, it kept things organized. Then the alpha male went away, and that system diffused. Now, people unite temporarily around big projects, out of passion or self-interest.”

Leadership failure explains some of this. Between directionless Tom Potter and every-direction-at-once Sam Adams, Portland has lacked a politically strong mayor for most of a decade. And despite the strongest field of contenders for the office since Vera Katz took on Earl Blumenauer in 1992, many insiders believe the best future mayor opted out in favor of keeping his current job. “If Jeff Cogen woke up tomorrow, said, ‘Fuck it,’ and ran, the race would be over in 15 minutes,” says one close political observer. That person is not alone in pining for a county chair of high competence and Boy Scout-ish charisma over the three major candidates actually pursuing the city’s top job.

An unsettled state may be natural in a nicey-nice town that prizes modesty even when it’s false. Portland’s process-oriented politics also rewards cooperation rather than individual vision. “The major change from 30 years ago is that everything is collaborative now,” says Mike Houck, the urban environmentalist who has done much to green Portland. “If something gets done, many hands are doing it.” (When we asked another environmentalist to name the next Mike Houck, he said: “There isn’t going to be one.”)

But the world changed, too. Corporate headquarters left—Fred Meyer, Pacific Power, PGE, Louisiana-Pacific, etc.—taking philanthropic and political heft with them. The daily newspaper that once orchestrated local opinion now often covers its hometown like an inexplicable foreign capital. And no one has much money.

“As resources from the state and feds decline,” says Ethan Seltzer, a professor in Portland State University’s Toulan School of Urban Studies and Planning, “the old idea that the city was a machine for spending money, with a few people who knew how to pull the levers, fades away.” As just one example, the Portland Development Commission, an ATM for savvy developers and key shaper of the Pearl and South Waterfront districts in the ’90s and ’00s, has seen its annual budget drop by more than $100 million since 2008.

The result is a wobbly construct, part past, part future. One day, organized labor teams up with big business to push the Columbia River Crossing, the proposed $3-billion megabridge to Vancouver. The next, the unions join Occupy Portland—a movement with no leaders anyone could name—and march alongside people who want to redesign capitalism. Portland can simultaneously suffer 9 percent unemployment and foster the entrepreneurial culture that Portland writer and New Republic contributing editor William Deresiewicz recently dubbed “Generation Sell.”

“We’re living in systemic change,” says David Chen, a venture capitalist. “The people who harness the power of that transitory state are the interesting ones.”

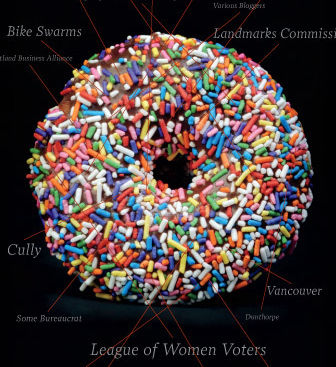

This calls for different—more Zen, if you will—leadership: the wit to pluck disparate trends out of the air (say, cheap rent in Chinatown and Japanese sneakerheads’ love of Nike) and throw them into the same test tube; or decide that this young architect should have dinner with that nonprofit exec. If there’s a hole in the doughnut of our civic culture, the right recipe can still be delicious.