The World Cup: A Cultural Guide

Image: Dan Root

Every four years, the world stops what it’s doing to watch soccer’s greatest drama. The World Cup’s 64 games can be savage or sublimely beautiful. Underdogs can topple giants. Nations can avenge centuries-old grudges. The greats of old fade away and new legends are born.

But the real beauty of the tournament is that for one month our complicated planet gets smaller, friendlier, and a whole lot louder. During the 2010 World Cup in South Africa, 3.2 billion people watched the games on TV. In the US alone, 94.5 million tuned in. In England and other developed nations, work productivity losses can be measured in the billions.

As the games kick off this month in Brazil, expect Portland to once again lend its voice to the global chanting. Whether you’re celebrating a win, mourning a loss, or peeking through your hands in the final, excruciating seconds, the Cup has a way of bonding you to people you otherwise might never get a chance to talk to.

We sat down with five such Portlanders to find out why they root. Meet your new best friends.

The Host: Muhamed Mujcic-Mufko, Bosnia

National Battle Cry: “Zemljo tisu-ljetna!” (“O you thousand-years-old land!”)

Image: Dan Root

On October 15, 2013, 442 Soccer Bar was alive with energy—the kind of energy only a tense game can generate. The bar’s owner, Muhamed Mujcic-Mufko had his eyes glued to the TV screens. His native Bosnia-Herzegovina was on the cusp of qualifying for the World Cup for the first time in the country’s history. The team needed to hang onto a razor thin 1-0 lead against Lithuania. As the game reached the final nervous minutes, Mufko, as his friends call him, promised beers to the two dozen bar patrons should the Zmajevi (the Dragons) secure a victory. Unsurprisingly, the small corner bar soon shook with chants of “Bosnia! Bosnia!”

Bosnia did win, just barely, and the team’s new fans got their beer. Mufko’s joy went deeper.

“The country is divided,” he says in a thick Balkan accent. “But sport is so strong. Maybe sport can put the country together again.”

Born in 1948 in the northern Bosnian metropolis of Banja Luka, young Mufko dreamed of becoming a professional soccer player, like his Dutch idol Johan Cruyff. But his pro soccer career was short-lived (“I had ability. But I didn’t like exercise. Second, I like drink and I like lady.”). Not long after, he began a career as a general contractor.

“We are poor country. But before the war we had really good life,” he says.

When Yugoslavia collapsed in the early ’90s, everything changed. Ethnic groups within Bosnia began a two-year civil war that would claim more than 100,000 lives. Mufko, his wife, and two daughters fled on one of the last flights out of the country—eventually landing in Portland on July 19, 1994, with $27 to their name. His 500 extended family members were either scattered or killed. Today, only one elder sister remains in Banja Luka.

At 442, which Mufko opened in 2010, football’s unifying power is on full display. Mufko pours beers, debates the sport’s minutiae with anyone who’ll listen, and welcomes new guests with a hearty “Hello, my friend!” When a couple of Timbers supporters complained that he was serving rival Sounders fans last year, Mufko calmly told them to be quiet.

“I don’t know politics. I don’t know economy,” he says. “But soccer is my life. I can always talk about soccer. Everything else, I don’t care.”

The Ally: Hilda Stevens, Guatemala

National Battle Cry: “Guatemala mi patria dorada!” (“Guatemala my country that I adore!”)

Image: Dan Root

One of Hilda Stevens’s most vivid childhood memories: her father, a Guatemalan soccer referee, telling her mother to keep the car running even before the game he was officiating had begun. Every once in a while when the game was over, her father would make a dash for the car—a surging mob of the losing’s team’s fans on his heels.

“There’s always a warm part of me for the referee,” she says. “The winning team will praise them. The losing team will find something wrong.”

Stevens emigrated to Houston at the age of 8, where her father continued to referee (and continued to get harassed by fans), eventually landing in Portland in 1998. After more than a decade traveling the country as a software consultant, she opened Bazi Bierbrasserie off of SE Hawthorne Boulevard in May 2011, a Belgian beer bar devoted to showing soccer games on a single, communal screen. While Stevens’s native country failed to qualify for this year’s tournament, her loyalties span the globe: there’s the US, her fondness for her Belgian and German friends, and Costa Rica and Honduras, which are carrying the Central American torch.

“Latin American countries are pretty small, and we’re all experiencing the same economic challenges,” she explains. “There’s a unity. There’s that solidarity between us.”

Except, of course, when it comes to Mexico, the long dominant (opponents say arrogant) power in Central and North American football.

“It’s simple. If Mexico is playing, you root for the other Central American team,” she says. “If Mexico is playing the powerhouses, like Brazil or Argentina, then you root for those teams.”

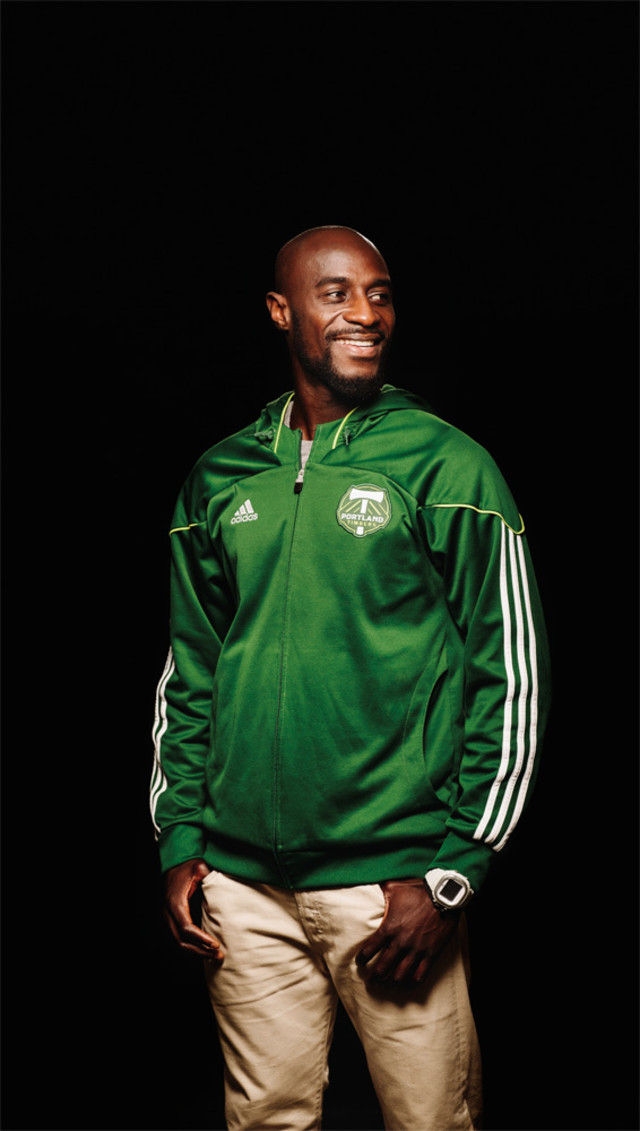

The Player: Futty Danso, Gambia

National Battle Cry: “To the Gambia ever true!”

Image: Dan Root

In 2001, an 18-year-old Mamadou “Futty” Danso hopped onto a bus jam-packed with people in his hometown of Serekunda, Gambia. He was about to skip the next two days of school—against his father’s strict orders—to ride 13 hours on dusty roads to watch his national team play its greatest rival, Senegal, to determine who would advance to the 2002 World Cup. At least, he hoped that the bus was headed there. He didn’t know, and he didn’t have any money. He was willing to take the risk.

“It’s like USA playing Mexico. Or Seattle playing Portland,” he explains. “You can’t miss it.”

The game ended in a 1–1 tie and a gigantic brawl between opposing fans. (“Yeah, I’m going to die,” Futty remembers saying to himself as he tried to escape the churning stadium.) He returned home a day later, exhausted but mostly unscathed. At least until his father found out.

These days, Futty enjoys his father’s begrudging approval of his long career at the Portland Timbers, where he’s played since 2009. Off the field, though, he reverts to the role of enraptured teen.

“If I’m playing, I’m way more relaxed than the fans,” he says. “But if I’m watching a game, I’m a normal fan. I get butterflies in my stomach. It takes a lot out of me.”

Since Gambia did not qualify this year (or any other year), Futty’s chosen team is Germany, a country with strong immigrant ties to Gambia, and unlikely to cause too much heartburn. But with daily Timbers practices, watching the games requires strict phone blackouts, DVR’ing, and most important, promises from teammates to not talk to him. The latter, he says, is hardest of all.

“Guys will tease me and say, ‘Hey, did you see what happened in that game?’ I say, ‘I don’t want to hear anything, I don’t want to know anything. Why are you telling me this?’”

The Patriot: Robert Cross, USA

National Battle Cry: “I believe that we will win!”

Image: Dan Root

In 2002, the USA played one of the most thrilling games in its short World Cup history. Facing mighty Germany in the quarterfinals, the Americans nearly scored several times in the opening minutes. Even when Germany scored first, the attack didn’t slow. That is, until a Teutonic defender notoriously stopped a US goal with his arm—and got away with it. The US, deflated, lost the game 1–0. But the fans were electrified.

“I’ve watched that match probably 20 times,” says Robert Cross, the president of Portland’s chapter of the American Outlaws, the team’s official supporters group. “We arrived on the world stage. There was a promise for the future.”

Twelve years later, that promise has yet to be fulfilled. But it’s getting closer. Maybe. In Brazil, in order to advance to the Cup’s knockout rounds, the United States will need to survive the so-called “Group of Death,” three historically excellent teams: Ghana, Portugal, and (yes) Germany. For Cross, a self-confessed glass-half-full kind of guy, the added difficulty sets the stage for the Americans to show they’re no longer amateurs.

“There’s still a belief around the world that we’re not that good. So every time we step out onto the pitch, we have something to prove.”

Born in 1973 in New Jersey, Cross quickly gravitated toward New York’s team, the Cosmos, which in the late ’70s and early ’80s starred some of the biggest retirees from Europe. But when he became friends with a neighbor kid from Italy, his soccer allegiance quickly took on a more nationalist breadth.

“The thing that took it to the next level, for me, was America was David—and the rest of the world was Goliath,” he says. “We would play great teams and we’d be lucky to score a goal. That became an addiction.”

Over the past 20 years, Cross estimates he’s missed seeing, in person, only two or three domestic national team games, flying all around the US to catch Gold Cup games, World Cup qualifiers, and friendly matches. When he moved to Portland in February 2006 to work for Energy Trust he happily discovered that Portland had a burgeoning soccer scene of its own. Since Cross started the AO’s Portland chapter, membership has risen to 800, mainly coming from the ranks of the Timbers Army. But he stresses that you don’t need to be a member to enjoy the national team.

“I just love the artistry. I love the beauty,” he says of other European teams. “Being from America, I want us to play that way within my lifetime. I know how hard that journey is.”

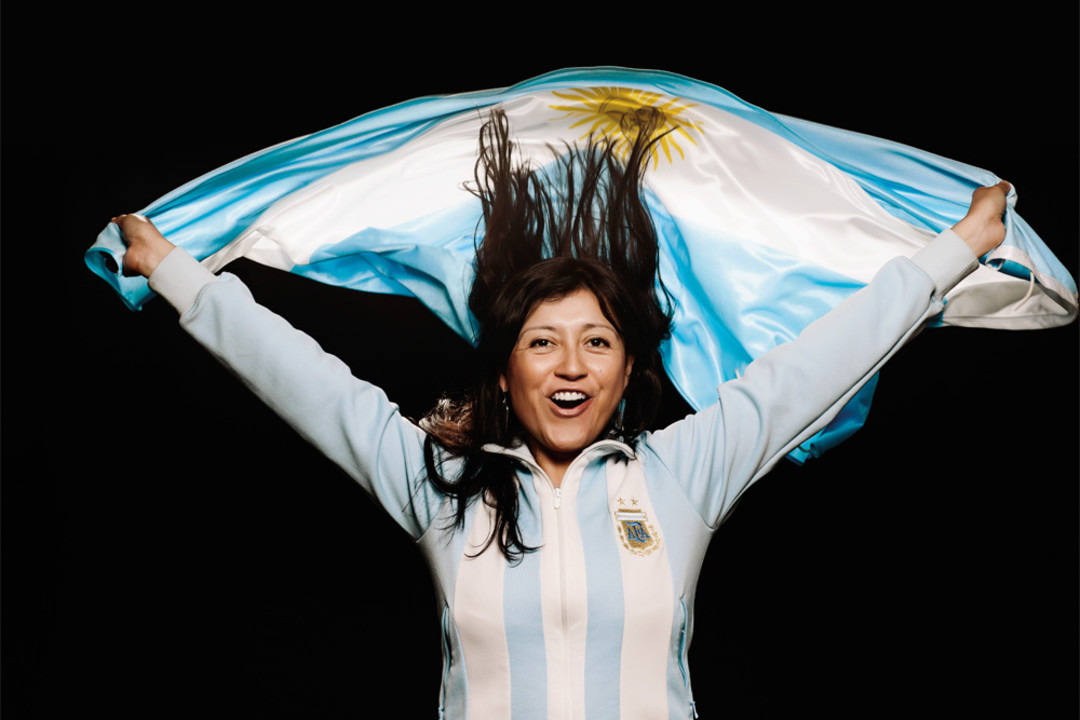

The Expatriate: Sole Avila, Argentina

National Battle Cry: “Vamos, vamos Argentina!” (“Let’s go, let’s go Argentina!”)

Image: Dan Root

For Sole Avila, soccer is about one thing: family. She was born in the Argentine countryside in 1978—the same year Argentina won the World Cup after defeating Holland, 2–1, in the dying seconds of extra time. Her brother, Maxi, was born in 1986, the next and last time Argentina won.

“During the game, everyone was there and no one talked, for 45 minutes,” she says. “Then we cry. My mom even cried. In 1986, it was so much emotion.”

When we she was 2, she moved to Buenos Aires, where her memories of games begin to blend together with family gatherings—particularly weekly barbecues. Fueled by Argentina’s ubiquitous malbec and Quilmes, the national lager, Sundays were an all-day food marathon: dozens of cousins, uncles, aunts, and distant relatives coming and going in the family’s backyard, eating facturas, picade, and asado, all to the constant soundtrack of soccer announcers in the background.

“Sunday is soccer day,” she says. “My dad would watch soccer, and listen to soccer on the radio all day long.”

In 2004, at age 25, Avila left her family and came to work as an au pair for a year. The trip was intended to be temporary (she had never left the country before except for a short jaunt to neighboring Brazil), but as for many Portlanders the city proved too friendly and nice to leave. These days, Avila is a medical coordinator at OHSU and became a citizen last year.

“The first week I arrived here, I fell in love with Portland. I think I’m still in love.”

While Avila hopes to someday return to Argentina, for now she’s content to watch the games from afar—without the threat of uninvited cousins popping in at any second—with her group of Brazilian, Costa Rican, and Thai friends.

“I love it,” she says. “Those 90 minutes they play are the fastest 90 minutes.”