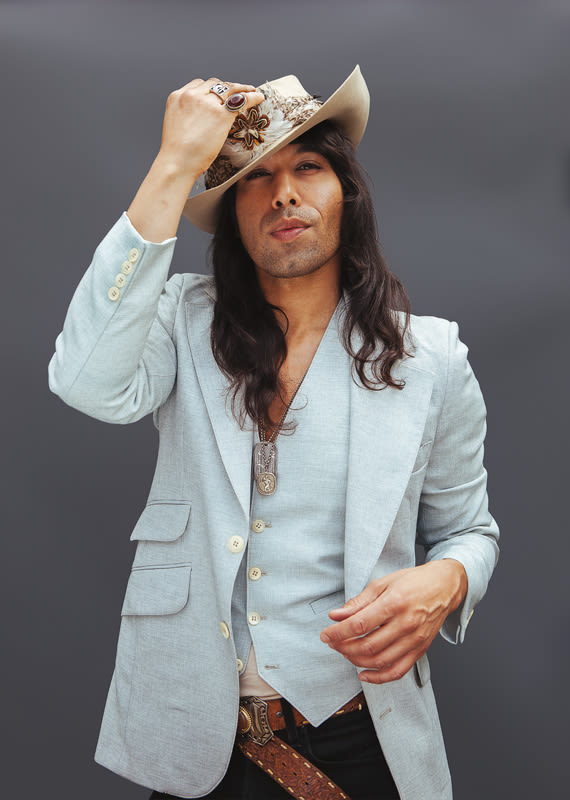

Talking Indie Stardom and Vintage Threads with Michael Maker

Image: William Anthony

In 1991, a Spokane band called the Makers roared onto the indie music scene, dressed in vintage finery and playing cocky garage rock—both in stark contrast to grunge’s plaid-clad depression. Behind charismatic singer Michael Maker, the band became known for a clannish intensity. (Though only two were brothers, all four members used the last name Maker.) At their peak, the Makers attracted an international following and released three albums on Sub Pop, the era’s flagship Northwest label. Today Maker, who at one point sold retro T-shirt designs to MTV, co-owns a venerated vintage store on NW 23rd Avenue called Pop-Up Shoppe. He still performs with the Makers and other bands—but he’s currently most excited about the music he’s making with his 9-year-old son, Harry.

As a teenager, I used to get together with my friends and my brother and just make noise. We all bought thrift-store guitars. I was the youngest, with the least money, so I ended up being the singer.

We came from a small, working-class town. Very conservative. Poor. Me and my brother, we’re obviously not completely white. My mother is Vietnamese. My dad’s German. My dad did two tours in Vietnam. He was a strong man, but had a voice like an angel and would sing us to sleep every night. When I was in high school, we went in to record with Scott McCaughey, who played with R.E.M. and the Minus 5. My dad took me and my brother aside and said, “You guys have already made it. In my mind, you’re a success.” He passed away and didn’t get to see a lot of what we did. We toured Japan, Europe, played huge festivals, got in all these cool magazines, and every time we accomplished something, the person we were doing it for wasn’t there to see it.

Most of the Makers’ existence happened before the Internet. When our album Rock Star God came out, Rolling Stone gave us a 4½-star review, which is almost perfect. Like, only reissued Beatles records get that rating. But you can’t find that review on the Internet. You have to go to the library and dig it out, as if it’s something from the 1880s. It’s like hearing tales of Davy Crockett fighting a bear.

We would never shy away from a fight. We liked the notion of being in a gang. Mainstream musicians were trying to prove they weren’t rock stars, wearing Chuck Taylors and cargo shorts. I’d go to thrift stores and find slim-fitting suits and Chelsea boots. At one point we wore all black with old tiger-tooth fangs around our necks, just to push the point: you’re not one of us! Now, everybody walks around in work wear, and none of them work with their hands. A lot of work wear, not a lot of work going on. It’s a good look, but it’s just another look.

Vintage clothing has always been a passion. I had a store in Spokane when I was about 19, very 1960s focused: mod, pop art. Now, I sell old motorcycle club, hot rod, military stuff. Anything cool. I love Batman. I also do a space in Sellwood with more high-end stuff. Out-of-town dealers come up and we’ll talk for three hours about one jacket. For an onlooker, it’d be like listening to some nerds talk about Star Trek.

I’ve been running Pop-Up Shoppe for seven years. I’m like the lord of Northwest 23rd. I only say that because I don’t want to say mayor. Who wants to be the mayor?

A child won’t allow the parent to be cool. All my cool, sexy dancing I prided myself on all these years—that just won’t fly with my son. My cool clothes mean nothing. Having a child gives you a lot of clarity. You start to see everyone as a child. You’re so much more forgiving.

My band with my son is probably the best thing I’ve ever done. I play guitar and he plays drums. He doesn’t know how bad I am—he’s too young. He’s starting to get an idea, though. I’m probably going to get replaced any day.