Researchers Unlock the Secrets of Panda Sex

Deforestation. Tourism. Climate change. We haven’t exactly made it easy on the giant pandas, sad mascots of animal endangerment. Only 1,900 still roam the wild.

But there’s a more intimate reason why pandas are scarce. Female pandas ovulate only once every year, leaving a razor-thin window for successful conception. Some zookeepers take creative approaches to help their chances: dose ’em with Viagra, load up some panda porn—literally, a video of two pandas mating—and hope for the best.

“The theory was that some of the pairs that were sent away from China may not actually know how to mate,” says Meghan Martin-Wintle, an Oregon Zoo researcher. “As far as I know there is no scientific basis for this practice.”

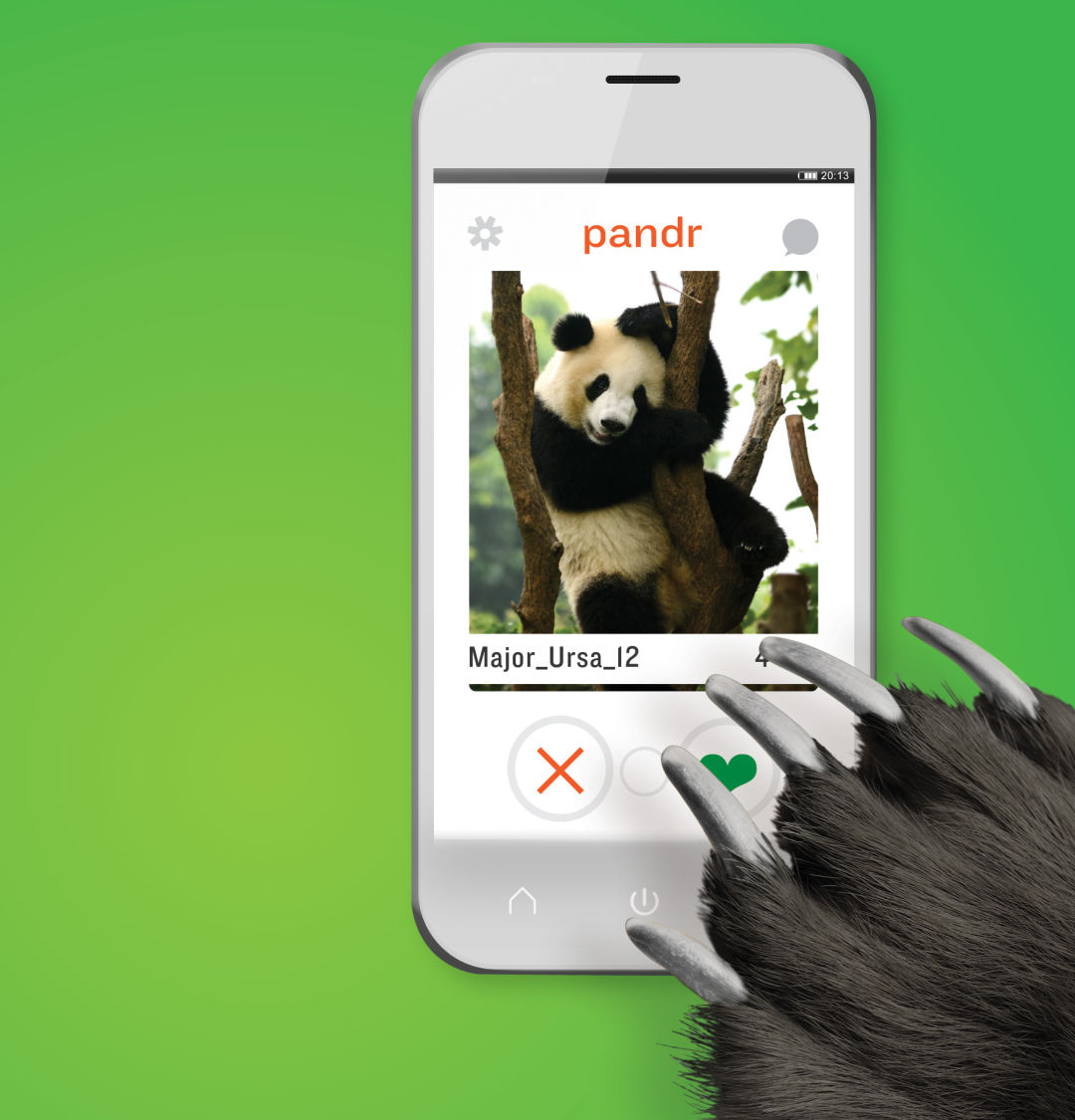

Martin-Wintle has a better idea: just let pandas choose their own mates. Starting in 2011, she, along with Oregon Zoo deputy conservation manager David Shepherdson and a team of Chinese researchers, studied 40 pandas in a Chinese zoo, allowing females to choose between two potential mates through a mesh barrier. If her crush reciprocated, Tinder-style, by scent-marking or making chirping noises, the handlers let that pair play “hide the bamboo.” The result: an 80 percent increase in reproductive success.

“Initially, we were surprised, though maybe shouldn’t have been,” says Martin-Wintle. “If a female is limited to a number of offspring she can have, she will be motivated to find traits that result in their offspring having a higher probability of survivorship and eventually a higher probability of breeding.”

Martin-Wintle, now doing postdoctoral work at the San Diego Zoo, is studying why mutual mate choice matters. Historically, female mate choice was seen as more important as they were theoretically more invested in their offspring. The results could revolutionize how mammals are bred in captivity.

Says Martin-Wintle, “We’re trying to get the captive breeding program as close to the natural mating system as possible.”