One History Sleuth’s Radical Theory: Everything We Know About How Portland Began Is Wrong

“‘This man Overton stalks through the twilight of these early annals like a phantom of tradition, so little is known of his history, character and fate.’”

—Harvey Scott, “History of Portland, Oregon,” 1890

There was a time when Portland was just trees on a long winding river, a place men reached after hard journeys in wagons and boats, where everything that we know now was nothing at all.

It was a time when a town could start at the mere toss of a coin. Or at least that’s how Portland’s famed “Portland Penny” story goes. It’s an oft-told tale, repeated and passed down for generations and cherished as evidence that the city’s eccentricity is genetic. According to this lore, Portland came to be in 1845 when business partners Asa Lovejoy, a Boston lawyer, and Francis Pettygrove, a Maine merchant, argued over what to call their land claim on the banks of the Willamette. The gentlemen tossed a penny and agreed that the winner would name the place for his hometown. Pettygrove won, Portland became Portland: a tale so unusual, even the New York Times published the “interesting story” of the town way out west that started with a coin flip.

Great stories bear repeating. And Lovejoy and Pettygrove’s tale was repeated and retold, a copper coin flipping over and over, again and again, through time and Portland’s foundational lore. The Oregon Historical Society, repository of the state’s frontier heritage, has owned the titular coin since 1910.

But time changes stories. Did Columbus “discover” America? Did Betsy Ross sew America’s first flag? Did two guys named Lovejoy and Pettygrove, alone, really plant Portland’s seeds?

One evening in April 2016—170 years and some change after Portland first emerged from the stumps of the riverbank—a 40-year-old Missouri native named Randall Trowbridge addressed a small crowd inside Northeast Portland’s restored Markham House, a group drawn by his cryptic email invitation: “Early Portland: An Enigma Revealed.”

Trowbridge, a plain man in an olive brown, button-down shirt tucked into jeans, stood in front of the audience and thanked them for coming. “I’ve been living with this terrible secret for so long,” he said. The room laughed.

Over the next 90 minutes he presented two years of research, a director’s cut version of a strikingly different Portland’s origin story: an argument that the age-old story of Lovejoy and Pettygrove is largely missing a key player, the person who was Lovejoy’s original partner in the land claim and—Trowbridge thinks—actually had the idea of Portland.

Before a rapt crowd of scholars and history buffs, some of whom audibly gasped at his revelations, Trowbridge produced evidence that he says shows that founding a town here was originally the vision of an illiterate Southerner, a rough pioneer carpenter, a man with Native American blood, who one historian once wrote stalked “like a dim wraith through the pages of history.”

Trowbridge believes he has done something that no researcher has done before: unlocked the mystery of William P. Overton.

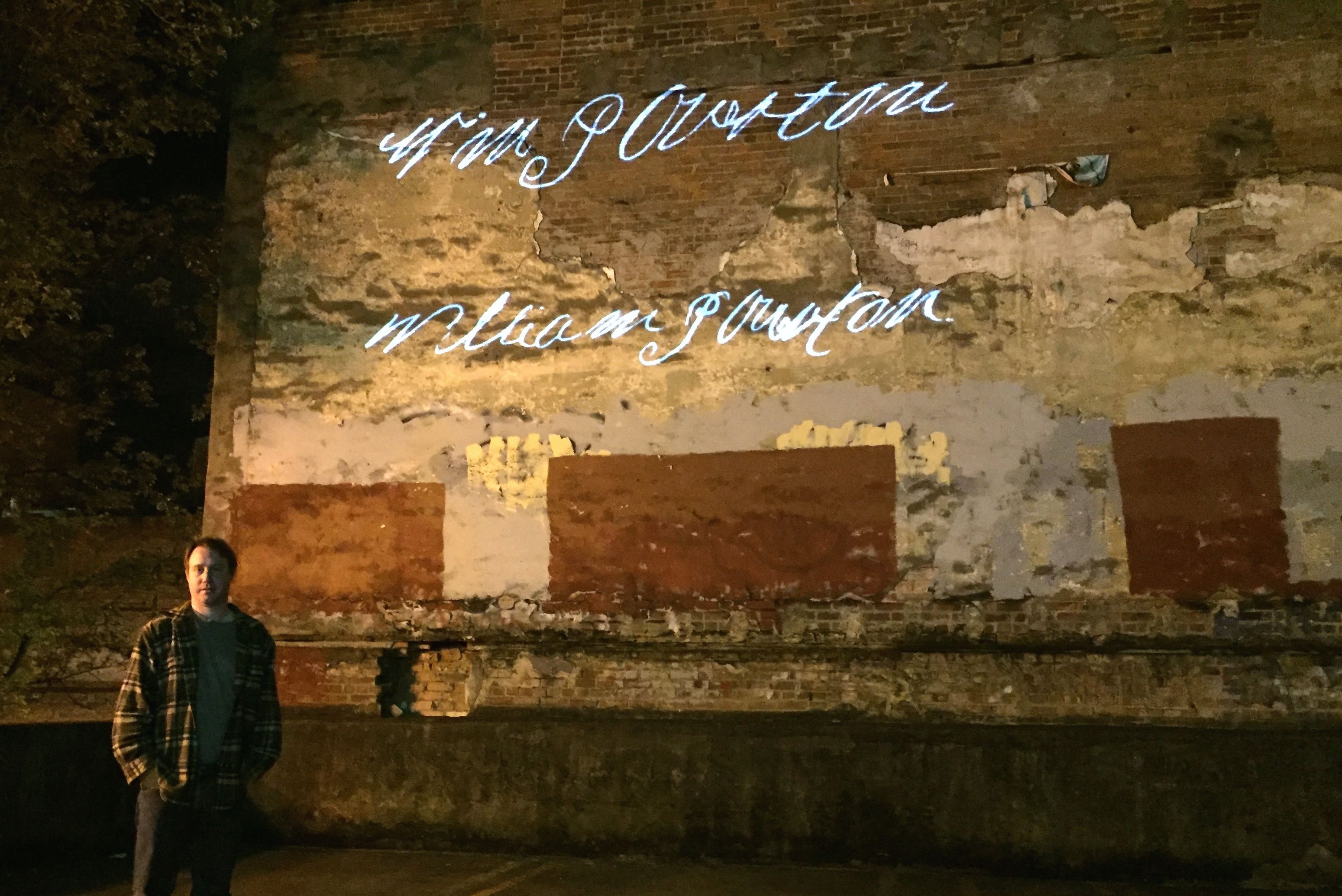

Randall Trowbridge on Overton Avenue ... in Missouri.

Image: Courtesy Randall Trowbridge

Trowbridge is an operations manager at a software company. He loves classical music and often wears a giant flannel shirt over a Columbia Records tee. He didn’t graduate from college. He carries his notes tucked inside a folder of Franz Liszt sheet music, and bristles equally at being called an “amateur” and a “historian.” “I don't know what I am," he says.

We meet for the first time in late March, after Trowbridge e-mails me to claim that Overton is “the D. B. Cooper of the Portland story.” When I arrive, he sits in a back booth at McMenamins Tavern and Pool on NW 23rd Avenue with his friend Dan Haneckow, another local historian. Not far away in Northwest Portland’s Alphabet District, Overton’s name graces a street, alongside those named for Pettygrove and Lovejoy. But otherwise, he’s far from a city father—more like a historical phantom. A search for Overton, in a library or online, will produce few facts and some vague allusions to death by hanging in Texas.

Haneckow slides a black binder across the table, one filled with every historian’s reference to Overton he could find: “Overton was a mere bird of passage,” wrote Joseph Gaston in his 1911 volume of early Portland history. “No one knew where he came from and where he went to.” Most established accounts tell a similar story: Overton, a penniless drifter, exchanged a 50 percent interest in the original Portland Claim with A.L. Lovejoy because he couldn't afford the 25-cent filing fee, then sold off his claim to Pettygrove when he couldn’t afford the 25-cent filing fee, only to wander toward Texas and a murky, possibly criminal, fate.

But for nearly four hours that night, Trowbridge shows me his research, and fleshes out a portrait of Overton assembled from 19th-century records, court depositions, old leather-bound journals, hand-scrawled census reports, newspaper clippings. Trowbridge’s journey began when he chanced upon an Oregon Historical Quarterly article, published in June 1937, that listed Overton as a member of the 1841 Bidwell Party—a 90-some-person expedition from Independence, Missouri, to California, from which a handful of members splintered off and traveled to Oregon. Trowbridge, in researching Bidwell, encountered a November 1890 article from a magazine called the Century. Late in his life, John Bidwell retold the story of the journey, recalling a night around a campfire when “an illiterate fellow named Bill Overton … loudly declared that nothing in his life had ever surprised him.”

While Overton’s specter-like presence in Portland history books lured Trowbridge, this glancing tale hooked him. “That was when I started taking this seriously,” he says.

And the man’s place in the Bidwell Party gave Trowbridge a clue on where to look for Overton’s backstory: his own home state of Missouri.

He had arrived at the point where many historians before him had probably stopped trying to trace Overton. For one thing, Trowbridge found that in 1840s Missouri, the name William Overton was as common as “Nick” in My Big Fat Greek Wedding.

But Trowbridge was unfazed: he looked for Overtons with more unusual names. In an 1830 census Jackson County, Missouri, he found one: Moses Overton Jr.

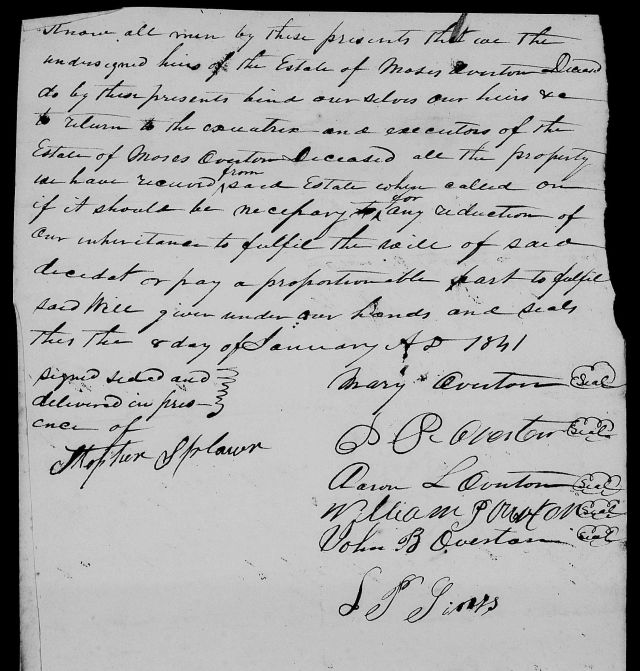

On this bond, Randall Trowbridge first glimpsed William Overton's signature.

Image: Courtesy Randall Trowbridge

The seas of documents parted, leading Trowbridge to the will of Moses Overton Sr., an Alabama man, in which Trowbridge found a simple but now-shocking line: “I give and bequeath to my son, William Overton, a negro boy named George.” And with it, a bond, signed: William P. Overton.

“I was like, ‘Oh my god, there’s his signature,’” Trowbridge says. “It just buried itself in my brain. I can see it when I close my eyes.”

He hoped it was the right William Overton.

Moses Overton’s will was filled with names of heirs, and so Trowbridge cross-referenced each of them, building out a family tree: brothers Jesse, Moses Jr., and William, sons of Moses Sr.

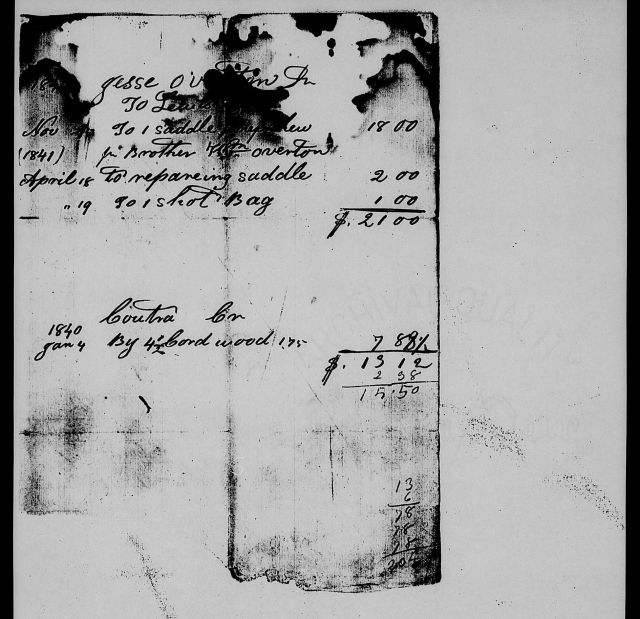

Trowbridge dug up the probate files of Jesse Overton, including the debts he owed when he died. Among them, there was a receipt for a saddle repair, purchased by “brother, William Overton,” charged to his brother's account.

In building the Overton family tree, Trowbridge discovered the mother of Moses Overton Sr. was named Mary Harjo, a name he found strikingly distinctive. Never deterred by a good rabbit hole, Trowbridge researched the name, finding that it was a common Creek surname. Furthermore, he found that Mary Harjo's son, Moses Overton, Sr. (Bill Overton's father), raised his family on Alabama land that had been ceded to the federal government by the Creek Indians—a tribe in which some members owned African slaves. If that means Mary Harjo was Creek herself—Trowbridge is still researching—that would make William Overton one-quarter Creek.

A receipt for a saddle repair paid for by William Overton

Image: Courtesy Randall Trowbridge

At McMenamins, as my head swims with information, Trowbridge explains what he thinks it all means: “The man who inherited the slave in Alabama is the person who goes on the Bidwell Party,” he says. “The person who goes on the Bidwell Party is the person who stakes the Oregon claim.”

A few weeks later, when we meet again, I ask him how he’s sure. If William Overton is such a common name, how does he know he’s got the right guy?

Trowbridge smiles and tells me to wait.

Randall Trowbridge grew up in Missouri, and moved to Portland in 2000. When I ask him why he has devoted so much time to chasing William Overton through forgotten archives, Trowbridge tells me that he never stopped being amazed at how the definite details of someone’s life—a life that was, after all, significant enough to the founding of Portland to justify the naming of a prominent street—could just vanish.

In the course of our conversations, I get the sense that Trowbridge has worried, at various times, that something similar could happen to him. He nods when I suggest this to him, saying that he lives in the shadow of giants: his brother went to MIT and works for Google; his father is the poet laureate of the state of Missouri.

“My whole life has been this feeling of ‘Well, I’m the one who just couldn’t get his shit together,’” the 40-year-old tells me at one point. “What this represents in my life is the moment I can come into my own.”

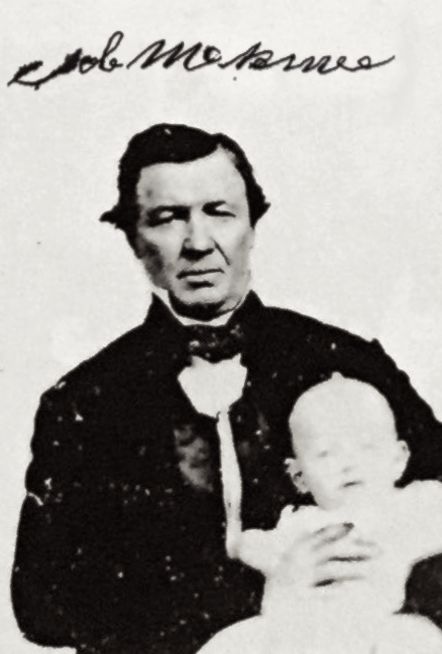

A few weeks after I first meet with Trowbridge, we walk on a sunny Saturday afternoon through Lone Fir Cemetery in Southeast Portland. Trowbridge points at the headstones of Portland’s early elite: James B. Stephens, Dr. James Hawthorne, Asa Lovejoy. We’re searching for the grave of a man named Job McNamee, another crucial part of Trowbridge’s research on Overton.

You could argue that McNamee provides the earliest proof of the city’s affinity for quirk: In the 1840s, he opens Portland’s first bowling alley, the Ball Alley House. Trowbridge finds reports of McNamee being charged with gambling and selling spirits. “He sounded like a pretty fun guy if you were hanging out in 1840s Portland,” he says. (Coincidentally, McNamee hailed from St. Joseph, Missouri, where Trowbridge was born.)

Job McNamee

Image: Courtesy Randall Trowbridge

But McNamee’s story, as Trowbridge has discovered it, painted a picture of early Portland that is less “Little House on the Prairie and a little more Deadwood,” he says. It begins with the land for the place that became Portland, originally owned by Overton.

Despite Overton’s vague presence in history books, his initial ownership of the Portland claim has never been contested. Carl Abbott, a renowned local historian, confirms: “He showed the site to Asa Lovejoy and they became co-owners.”

Lovejoy himself recalled his first encounter with Overton to historian Hubert Howe Bancroft in 1878. Printed in a September 1930 edition of Oregon Historical Quarterly, “Lovejoy’s Pioneer Narrative” tells of a meeting of strangers at Fort Vancouver. As the pair traveled toward Oregon City, in a canoe paddled by Native Americans, Lovejoy recounted that Overton told him, “If you want a claim, I’ll give you the best claim there is around here.”

This is common knowledge; it’s the next part that gets sticky.

Trowbridge continually read stories of Overton being unable to afford the 25-cent fee to file his land claim. “Overton is a drifter,” Abbott confirms.

But Trowbridge, in his research, found something that suggested that Overton went to the Sandwich Islands, now known as Hawaii, after selling to Pettygrove. Trowbridge found ship manifests listing Overton’s arrival in Hawaii and proof of him working there as a carpenter. (So much for his having been hanged in Texas.) And, even more, he finds Overton listed as a passenger on boats arriving again in Oregon.

Here’s how McNamee comes into this, continues Trowbridge: After Overton is gone, Lovejoy soon sells his share to Benjamin Stark, a merchant. Pettygrove, who buys Overton’s claim, lives in Oregon City. At the time, it’s the seat of Oregon’s frontier provisional government and, really, the only substantial town around. Pettygrove can own the Portland claim and not live on it, Trowbridge says, because 1845 land laws allow absentee ownership—but this changes in 1850. As Trowbridge scoured early ownership of the Portland land claim, “something that always confused me was that in 1848, Pettygrove files another claim.” Why would he file a claim for land he already owned?

So Trowbridge looked back further. McNamee—living in Portland and running his bowling alley—must have anticipated the coming change, filing a claim for the town site in 1847. But when Trowbridge found that claim, he noticed something scrawled over the text: a note, “abandoned at written request of the claimant,” effective February 16, 1848.

One day later, “Frank Pettygrove records his second claim,” Trowbridge says.

Eventually Pettygrove sells. Daniel Lownsdale, a tanner, splits Pettygrove’s claim with Stephen Coffin and William Chapman. But then comes a contentious legal fight between Lownsdale and his partners. In court arguments, attorney Montgomery Blair (later Abraham Lincoln’s postmaster general) says Pettygrove fraudulently canceled McNamee’s claim — perhaps forcing a clerk to write that McNamee abandoned his own claim. And even more, when McNamee bragged of his right to the Portland land, Pettygrove showed up on one occasion “armed and accompanied by his friends.” In Blair’s account of the Portland story, Pettygrove figures as a man who “spoke of having settled the controversy between him and McNamee by his pistols”—something like Deadwood crime boss Al Swearingen, the real-life figure so memorably portrayed by Ian McShane in the HBO series about the lawless gold camp.

So if Pettygrove was the thuggish frontier fixer who seized control of the tiny settlement, and McNamee was the hapless dupe who lost it, who was William Overton?

Deep in those legal briefs—pages and pages of documents located in a private Chicago library — Trowbridge found the answer: a deposition given under oath by Lovejoy in 1852, in which he said Overton “induced him” to examine his land claim as a potential town site.

Overton, Trowbridge argues, was the man who had the idea of making a city where Portland stands today. He was selling Lovejoy on the idea of a town.

“It changes forever who Overton is in the story of Portland,” Trowbridge says. “He’s not the hobo down by the river who needs to be evicted so you can start your town. Overton is the guy who has the idea to make a town in the first place.”

By mid-April, when Trowbridge takes his position in front of a projector and tells the room of history buffs the story I’ve already heard, I’m wondering if they’ll see something I didn’t. A hole in his story. A fatal flaw.

Nearly two hours into his presentation, Trowbridge has one last trick: provisional document 683. It’s a petition over the Oregon land law, asking for absentee ownership. Trowbridge found it one day after we first met, when he took a day off work to scroll through microfiche at the Oregon State Archives.

“I just about had a heart attack,” he says to the crowd, “because there at the top of the page, one of the very first signatures”—he pauses, his presentation zooming in on just one name—“is William P. Overton.”

It’s the same looping signature Trowbridge saw from the Alabama estate files. The same sweeping W, the curled P. The signature that burned itself inside Trowbridge’s eyelids—the object of his obsession.

“I found something I never thought I would find,” he tells the crowd.

He’s talking about the document—how it confirms that the Overton he detected in records in Missouri and Alabama is the same Overton who claimed an unnamed place in Oregon.

But I think he’s also talking about finding himself, too.