Kate Brown Was Supposed to Be America’s ‘Radical Feminist Governor.’ What Happened?

Last spring, with the future of reproductive rights in the United States in doubt, the woman once cast as the West Coast’s defiant answer to the Trump presidency was speaking directly to a 9-year-old girl in light-up high-tops. Gov. Kate Brown, likewise in sneakers, stood just a head taller than the elementary school student.

“I started fighting for choice when I was a little older than you,” Brown, 62, told the girl, who also wore a pink headband with a protruding unicorn horn and clutched a homemade poster that read “nacho uterus.” (Next to the words, a hand-drawn womb floated in a bowl of chips and salsa.)

The occasion for the exchange was a May 14 press conference in Portland’s World Trade Center to underline Oregon’s support for abortion rights. It followed Politico’s bombshell publication, two weeks earlier, of a leaked US Supreme Court draft opinion that showed a majority of justices were poised to overturn Roe v. Wade—a dramatic change the court officially carried out June 24, with a sorrowful and furious dissent from its three liberal justices. The now-voided 1973 decision had once prompted a 13-year-old Brown, the eldest of three sisters, to persuade her Republican mother to ditch the GOP.

“I will not stand by,” Brown said to rolling television cameras at the press conference. “Generations, myself included, have fought to expand and protect the rights that women have today. And no matter what the Supreme Court does, this fight will continue because everyone, everyone should have the power to make their own health care decisions and decide their future.”

In the concentric circles that surrounded Brown that day in Portland, this one—with the third grader and fellow elected Democrats, including US Sen. Jeff Merkley and Oregon Attorney General Ellen Rosenblum—was the tightest and the coziest. “My biggest fan club are girls under the age of 15,” Brown later said in an interview. “If girls under the age of 15 could vote, I’d be getting 100 percent.”

Outside the press conference, the fan club grows more diffuse.

Abortion isn’t under threat in Oregon; lawmakers enshrined reproductive rights into state law in 2017, a signature accomplishment of Brown’s. Fifteen-year-old girls don’t vote. And Brown faces a downright hostile reception among much of the public as she prepares to leave office in January, eight years after ascending to the top post when former Gov. John Kitzhaber resigned a month into his fourth term, amid corruption questions, ceding the job to Brown, then secretary of state. (Term limits restricted Brown from running again in 2022; Kitzhaber’s four terms were not consecutive.)

In November 2021 and April 2022, Brown recorded the lowest approval rating of any US governor, including the eight other women who then held the position. “This is not a governor who has led significant change,” says Liz Kaufman, a Democratic political consultant in Oregon. “But she has held down the fort.”

This less-than-rosy reality marks a sharp turn from 2017, during the era of Donald Trump, when the New Yorker cast Brown in the role of “America’s radical feminist governor” and declared that “she may well have the broadest mandate of any progressive governor in the country.”

Brown, the magazine reported, was perhaps the closest of any of Trump’s opponents to being his “personal antithesis,” and Brown grasped the magnitude of the moment. She told the magazine she was ready to tackle everything from cap-and-trade to universal health care.

Just a few years later, in the throes of early-stage pandemic, the same publication would observe that Brown was facing down an influx of protesters toting Trump-reelection signs and ones that targeted her—“I’d rather have COVID than KATE,” “Down with Dictator Kate!” and “Kate Brown for prison!”

Where did things go wrong?

In the years that followed Trump’s election, Brown leaned into that leftist-leading-lady energy. She welcomed Muslim refugees when the president curtailed their entry into the US. She championed clean-energy legislation when Republicans professed skepticism of climate change, signing a 2021 bill that the Associated Press deemed “one of the most ambitious timelines in the country for moving to 100 percent clean electricity sources.” To curb suicides and mass shootings, she required gun owners to secure their weapons and empowered courts to remove them from people’s possession at the request of worried family members or law enforcement. She also appointed a historic number of women and Oregonians of color to public commissions and judicial seats while white men bemoaned their loosening stranglehold on power. Four women are now on the seven-seat Oregon Supreme Court, including the first Black justice, Adrienne Nelson, who has since been nominated for a US District Court seat.

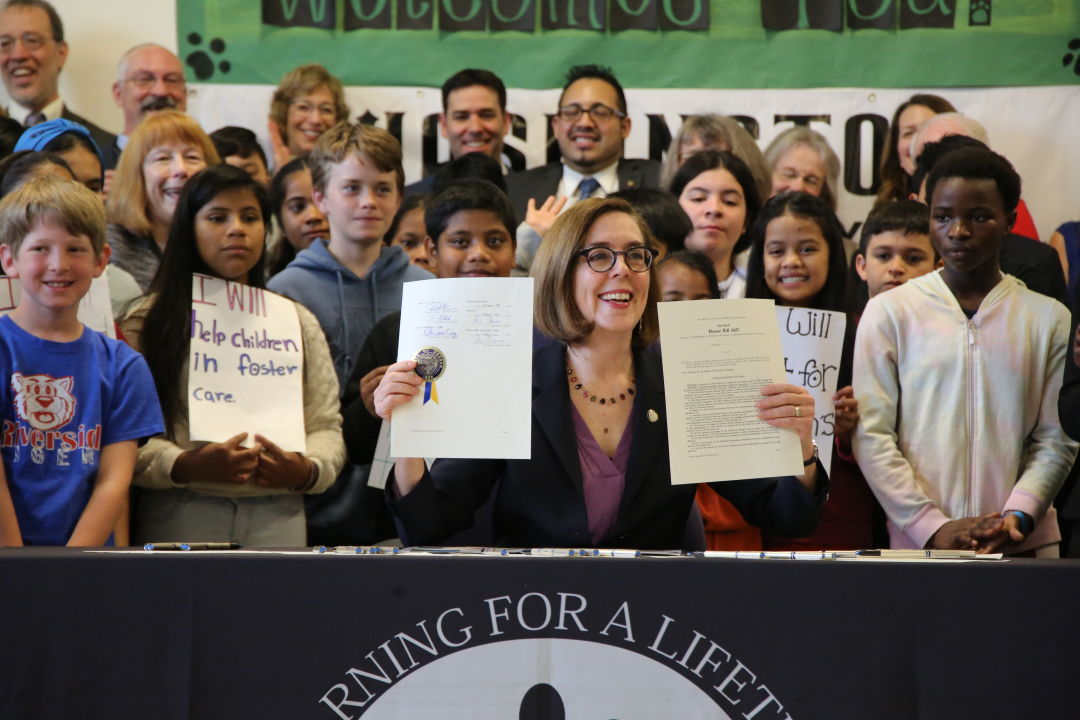

Kate Brown signs the Student Success Act

Brown counts among her achievements the creation of Oregon’s Racial Justice Council, a group of 30–40 high-profile community leaders whom she credits with “changing how state government budgets and how I hope governors in the future develop their legislative agenda.” She also touts Oregon’s automatic voter registration system and the Student Success Act, a 2019 law that enacted a gross receipts tax on Oregon businesses and raised an additional $1 billion for public schools.

Somewhat more controversially, Brown also takes credit for keeping COVID-19 infection and mortality rates relatively low during the pandemic, although she has drawn criticism for not opening K–12 schools sooner and imposing major restrictions on businesses.

“I thought we had it wrong when bars and restaurants were open and schools were not,” says Tobias Read, the state’s elected treasurer who ran unsuccessfully for governor in 2022’s Democratic primary. “I think she gets credit for making tough decisions, and a lot of Oregonians are alive and better off as a result. But it did come at a cost, and schools have such a central role, for the experience of students and families, and the economy as well.”

Brown doesn’t second-guess.

“We were literally building the airplane as we flew it,” Brown says. “Do I wish we had, you know, figured out a way to have kept schools open? Absolutely. We’ve all seen the impacts. That’s why I fought to get teachers vaccinated early, because I wanted to get kids back into school as quickly as possible. But the other challenge was that our country and our state, all of the states, none of us were prepared for this once-in-100-years pandemic, and the Trump administration intentionally—I mean, it felt like the Hunger Games, right? They intentionally rewarded states for doing the wrong things.” (Florida, she says, got 100 percent of the personal protective equipment it requested, while Oregon got just 17 percent.)

Her COVID response alone doesn’t explain Brown’s negative numbers, and

neither does sexism, although the governor said that she suspected misogyny and homophobia have contributed. (She also isn’t a huge fan of her media coverage, memorably telling Willamette Week that she thought both the Portland alt-weekly and the Oregonian had “peed all over me” for her COVID policies.)

Brown at the 2017 Pride Parade

Brown, the first openly LGBTQ governor of any state, has reigned during a period that was tumultuous for reasons beyond the global pandemic. Her tenure also included the 41-day armed occupation of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in 2016, the 2019 Senate Republican walkout to protest doomed cap-and-trade legislation, the 2020 racial justice protests in Portland that drew a militarized federal response, historic wildfires in September 2020, the deadly heat dome of June 2021, and the prolonged school closures of 2020–21 and their fallout.

“I don’t think there’s a governor of any party or any state who hasn’t received extra pressure and criticism during this period of time,” says former Gov. Barbara Roberts, the first woman to hold the office in Oregon and a mentor to Brown, the second. “And then if you add the fact that you’re a woman and a lot of people just don’t see you as a leader, it just complicates an already tough situation.”

Of course, the dire consequences of the pandemic spared almost no governor. Brown, a lawyer by training and a policy nerd who doesn’t tend to command crowds or inspire deference among lobbyists and fellow lawmakers who typically tower over her, suffered from self-inflicted wounds, too. The Oregonian catalogued them all: the Oregon Employment Department struggled to dispense aid amid the pandemic; rent assistance trickled to cash-strapped tenants; families of crime victims were furious when she granted clemencies without giving them any heads-up; and a new statewide family and medical leave insurance program has been postponed.

Amid it all, Oregon’s largest city morphed in the eyes of national media from the City of Roses to what gubernatorial candidate Betsy Johnson has dubbed “the city of roaches,” as city leaders wrestled with public camping, trash and graffiti outbreaks, a lack of affordable housing, rising gun violence, and downtown office vacancies that just won’t quit, among other issues. Brown and Portland Mayor Ted Wheeler, who might have gotten a shot at an open seat for governor had Brown not ascended to the job with Kitzhaber’s early exit, never quite seemed to be using the same playbook, let alone be on the same page. “It was a bad marriage,” says veteran lobbyist Len Bergstein.

Brown, who used to represent Portland in the state legislature, says she tried to intervene to help her home base during the roiling protest summer of 2020, even making a personal appeal to then-Vice President Mike Pence to ask federal law enforcement to back off during nightly clashes with protesters that were eagerly broadcast on Fox News. Wheeler, notably, declined Portland Monthly’s request to talk about Brown and her assistance to Portland, though his recent series of executive orders on houselessness, including camping bans on roadways, suggests that the city is done waiting for the state’s cavalry to come rushing in.

Brown says the knocks against her don’t knock her down. On days she expects to catch criticism, she warns her staff by using a gender-neutral alternative to “big girl” or “big boy” pants. “You gotta put on your metal underpants,” she tells them.

She regrets she will leave office without having tackled the ballooning cost of college in Oregon. “Education is an elevator,” she said. “It enables anyone to rise.... My goal had been to figure out some strategies about how we make higher education more affordable and more accessible to more Oregon students. And the pandemic blew that all to shreds.”

Brown—who’s held public office since 1991, first as a state rep and then as a state senator, before rising to statewide office—declined in her interview with Portland Monthly to hint at what she may do next after she leaves office early next year. As voters turn their attention to the campaign for Oregon’s next leader, they’re unlikely to see Brown on the trail. Oregon’s 39th governor—Democrat Tina Kotek, unaffiliated candidate Betsy Johnson, or Republican Christine Drazan—won’t share too many policy ideas with each other. But there’s one thing they’ll all try to claim, with varying degrees of success: they’re not Kate Brown. (She has endorsed Kotek, but as of press time the two hadn’t made significant campaign appearances together.)

For her part, Brown claims she’s unfazed by the negativity. “GSD,” is her retort. In other words, she “got stuff done.” Now it’ll be the next woman’s turn.