A Much Rougher Portland Origin Story Than You Know

Image: Amy Martin

The coin toss.

At some point, all Portlanders learn about the coin toss: that in 1845, when the city came to be, business partners Asa Lovejoy, a Boston lawyer, and Francis Pettygrove, a Maine merchant, argued over what to name their riverbank land claim. The gentlemen tossed a penny, and agreed that the winner would name the place for his hometown. Pettygrove won and Portland became Portland, a city with eccentricity woven into its foundation myth.

It’s a great story. But could it really have been that simple?

One evening in April 2016—170 years and change after Portland first emerged from a field of stumps along the Willamette—a 40-year-old Missouri native named Randall Trowbridge addressed a small crowd inside Northeast Portland’s restored Markham House, a group drawn by his cryptic e-mail invitation: “Early Portland: An Enigma Revealed.”

Trowbridge, dressed in an olive-brown, button-down shirt tucked into jeans, stood in front of the audience and thanked them for coming. “I’ve been living with this terrible secret for so long,” he said. The room laughed.

Over the next 90 minutes he presented a strikingly different Portland origin story, one that adds a long-shadowy player: an illiterate Southerner, a rough pioneer carpenter, a man with Native American blood who, in one writer’s description, stalked “like a dim wraith through the pages of history.” Trowbridge believes he has done something no researcher has done before: unlocked the mystery of William P. Overton.

In standard accounts of Portland’s origins, Overton makes a cameo as a drifter who briefly held the original 1843 land claim to the clearing that became downtown Portland. Though his name graces a Northwest Portland street (alongside those honoring Pettygrove and Lovejoy), he vanished from the city’s annals early, after splitting the claim with Lovejoy in exchange for the 25-cent filing fee, and ultimately selling out to Pettygrove.Then, the story goes, he wandered off to Texas, where maybe he got himself hanged. A 1911 history describes Overton as “a mere bird of passage.”

Randall Trowbridge—by day, a software company operations manager, by night, a classical music and history buff who stuffs his research notes in a folder of Franz Liszt sheet music—became interested in William Overton after he chanced upon an old Oregon Historical Quarterly article. That piece listed Overton among an expedition from Missouri to California, from which a handful of pioneers splintered off for Oregon. He soon found a second reference to “an illiterate fellow named Bill Overton ... [who] loudly declared that nothing in his life had ever surprised him.”

These traces intrigued Trowbridge. He dove deep into archives from the 1830s and 1840s in Missouri (which also happens to be his home state) and Alabama, where an old will led him to evidence that William Overton may have descended from a Creek woman. He unearthed signatures and stray property records, chasing Overton through the documents.

Eventually, the trail led to primordial Portland, a place Trowbridge describes as less “Little House on the Prairie and a little more Deadwood.” Behind the simple, quirky story of the Pettygrove-Lovejoy coin toss, he found a tangled legal battle over the original Portland claim. That case’s documents describe Pettygrove showing up to negotiations “armed and accompanied by his friends,” and as a man who “spoke of having settled the controversy ... by his pistols.”

And deep in the court briefs in Chicago’s private Newberry Library, Trowbridge found a deposition given under oath by Lovejoy in 1852, in which he said Overton “induced him” to examine his land claim as a potential town site. Overton, Trowbridge argues, was the man who had the idea of making a city where Portland stands today.

“It changes forever who Overton is in the story of Portland,” Trowbridge says. “He’s not the hobo down by the river who needs to be evicted so you can start your town. Overton is the guy who has the idea to make a town in the first place.”

In other words, the famous coin toss happened—as Trowbridge sees it—only because Overton looked at a clearing and foresaw a city.

The first time I meet Trowbridge, we spend almost four hours poring over a portrait of Overton assembled from court filings, leather-bound journals, scrawled census reports, and newspaper clippings. Despite his lack of formal academic standing, he bristles at being called an “amateur historian.”

“I don’t know what I am,” he says.

As for why he’s devoted so much time to the pursuit of William Overton, Trowbridge tells me that he never stopped being amazed at how someone’s life—a life, after all, significant enough to justify the naming of a prominent street—could just vanish. In the course of our conversations, I get the sense that Trowbridge fears something similar could befall him. He nods when I suggest as much, saying that he lives in the shadow of giants: his brother went to MIT and works for Google; his father is the poet laureate of Missouri.

“My whole life has been this feeling of ‘Well, I’m the one who just couldn’t get his shit together,’” Trowbridge tells me at one point. “What this represents in my life is the moment I can come into my own.”

His work has yet to be vetted by academic historians, much less published. Still, his sleuthing seems to have unveiled one of Portland’s most mysterious founders, and added a wrinkle to the city’s origin story. (Trowbridge also has assembled evidence that Overton left for Hawaii, not for a hangman’s noose in Texas, after selling his stake in the future city.) Beyond the substance of his potential discoveries, Trowbridge’s story serves as a reminder that history—of both the dusty past and the immediate present—is never really finished.

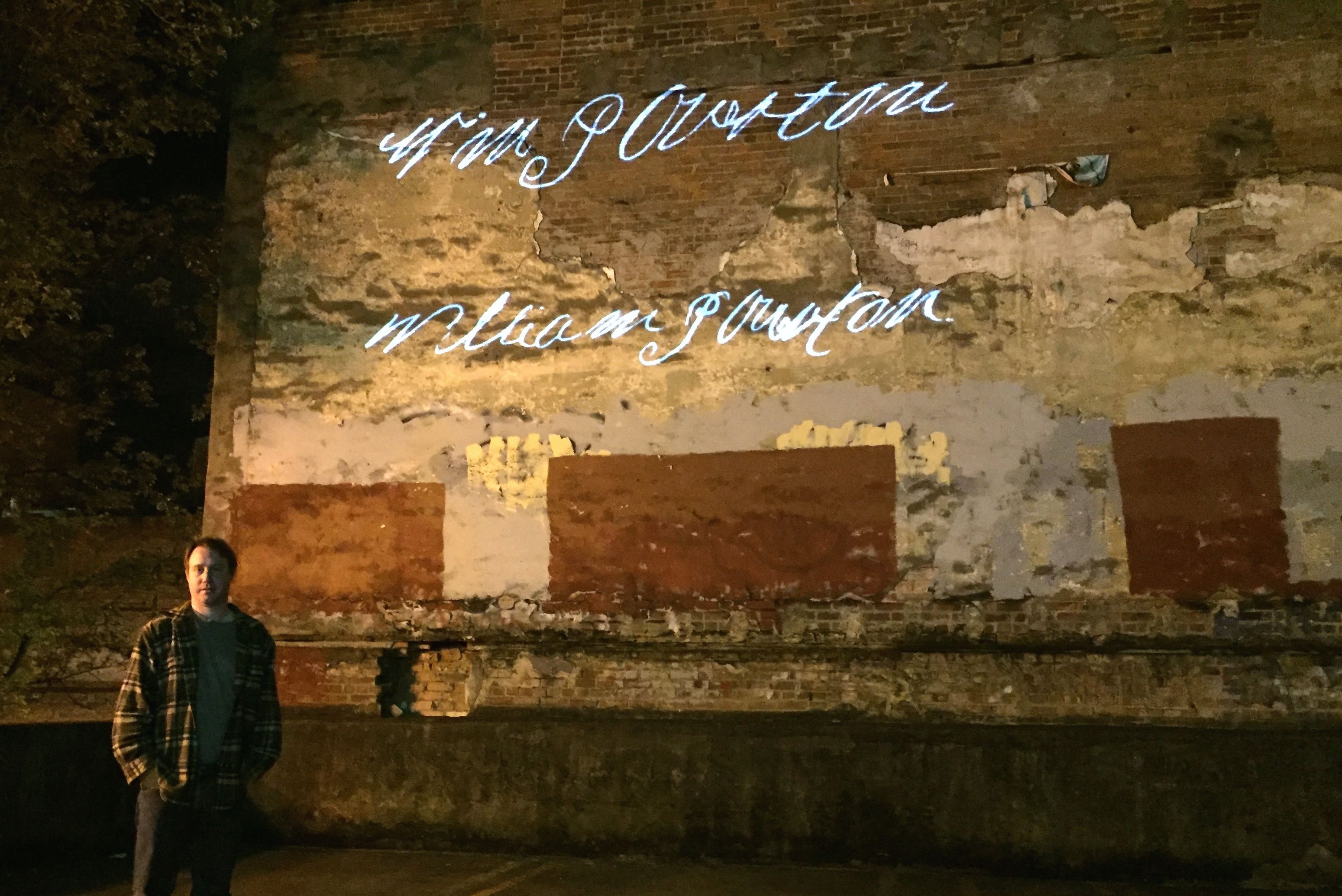

During his April presentation at the Markham House, Trowbridge displayed a slide of a looping signature, found in the Oregon State Archives: a match for the same name, found elsewhere, evidence that the Overton the self-appointed sleuth detected in records in Missouri and Alabama is the same Overton who claimed an unnamed place in Oregon.

“I found something I never thought I would find,” he tells the crowd.

He’s talking about the document. But I think he might be talking about himself, too.