All Kids Should Go Mushrooming—If They Can Keep Their Little Mouths Shut

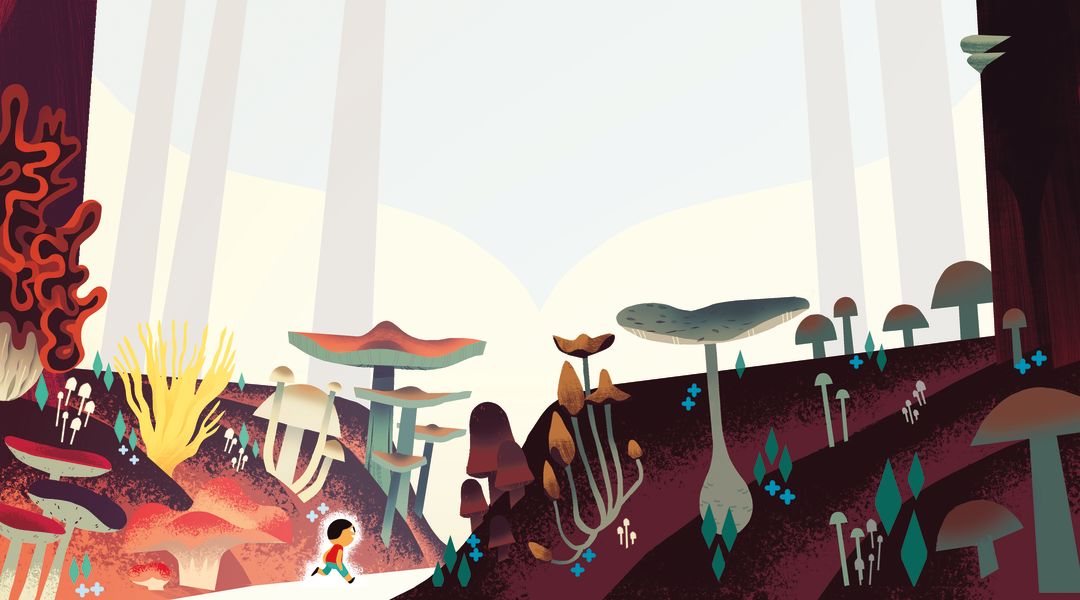

Image: Elle Michalka

Now that my oldest son is 4, I have heightened anxiety about our family ritual of mushroom foraging. No, not about poisoning. Americans are irrationally fearful of wild mushrooms. My family just follows the cardinal rule of mushroom hunting: when in doubt, throw it out. Of thousands of mushroom species, only a few are truly dangerous. Most “inedible” mushrooms would, if ingested, merely cause the same ultimately harmless unpleasantness as other, more mundane forms of food poisoning.

To be extra safe, we use sticks, not our hands, to turn over and examine mushrooms we haven’t identified. When my son, Sam, picks a mushroom, my husband and I double-check it before dropping it into the sack.

Not that he’d mistake, say, the smooth and elegantly veined funnel of a delicious chanterelle for its scaly-capped, sour-tasting relative, the woolly chanterelle. Kids are well-suited for foraging: observant and close to the ground. I learned to hunt mushrooms from a friend who is also a Montessori teacher. She views the activity as an extension of Maria Montessori’s belief that children gain self-worth from being useful and learning to care for themselves. Play is an important part of childhood. If that play happens outside—where modern kids don’t spend enough time, according to a growing body of research—and results in a tasty meal, even better. Mushrooms are rich in vitamin D, antioxidants, and iron, high in fiber, low in calories—though my usual treatment of sautéeing them in butter negates that last benefit.

Ever since Sam was a baby, he has accompanied my husband and me on weekend hikes in pursuit of these weird wonders, which occupy their own whole biological kingdom, distinct from plants and animals, and blossom from a mostly invisible mesh of tiny threads that run through forest soil. The first year, he rode in a carrier. Nestled against my or Scott’s chest, he breathed the cool fall air and, much of the time, napped.

The next year, he toddled along the uneven ground beside us. One of his earliest multiword phrases was “up the hill, finding mushrooms.”

By his third year, Sam knew what to do.

“I found some mushrooms!” he’d announce. I would bound over, pulling a knife from my pocket and congratulating myself on my little prodigy. Inevitably, Sam would add, “But they’re not the kind we eat or touch!” Mushroom hunting with kids means covering less ground and bringing home less food, but also having more fun than on an adults-only expedition.

This spring, Sam and I headed out in search of an early flush of morels. We didn’t find any, but we pretended to be astronauts exploring a new planet. We found some inedible fungus that Sam thought, rightfully, merited our admiration nonetheless: orange-striped turkey tails, staggered up an alder trunk like a fairy staircase.

As we drove home, I felt satisfied, albeit empty-handed. We’d had a great day together, the very definition of quality time. Then Sam asked, “What was that place called?”

My heart seized. That’s when the fear set in. Now that Sam is old enough to understand where we pick mushrooms, he could offer up our spots to anyone who asks. He’s a chatty kid, happy to start conversations with strangers at the grocery store or on the sidewalk.

I don’t ever reveal where I hunt mushrooms. True fungiphiles are tight-lipped like that. We may give a bag of matsutakes to a friend. But if asked where we found them, we evade. My friend Betsy, the teacher who got me hooked on foraging, goes a step further by never quantifying her harvest. She admits only that she found “enough for soup,” to deter bandwagon mushrooming motivated by volume.

A crop of mushrooms is frustratingly finite. Unlike the ski slopes of Mount Hood or the waves of Short Sands, if too many people go mushroom-picking, the attraction disappears completely. To a forthcoming preschooler, however, this secrecy sounds like lying. It’s exclusionary, an ethical gray area that prompts endless chains of Why?.

Now that he’s 4, I hope Sam starts to contribute more to our quarry. I want him—and, eventually, his younger brother—to overturn a swollen lump of duff and discover a king bolete, and to experience the accompanying rush of adrenaline. I want him to feel the addictive sense of satisfaction and gratitude that comes with finding delicious food, for free, sprouting from the earth.

Portland is widely hailed for its proximity to the Pacific Ocean and the Cascades, but to me the serendipity of its location is even more elemental: our geography’s soil literally bears fruit. What could be a more tangible sign that we live in a bountiful land? Even the ashes of forest fires yield delectable morels long before the landscape seems capable of sustaining life. Finding a wild mushroom feels, to me, like the universe is affirming that I am in the right place at the right time, that I belong here.

I want Sam to discover all of this. As he does, please don’t ask him where he picks mushrooms.