Who Will Be Crowned the World’s Greatest Tetris Player?

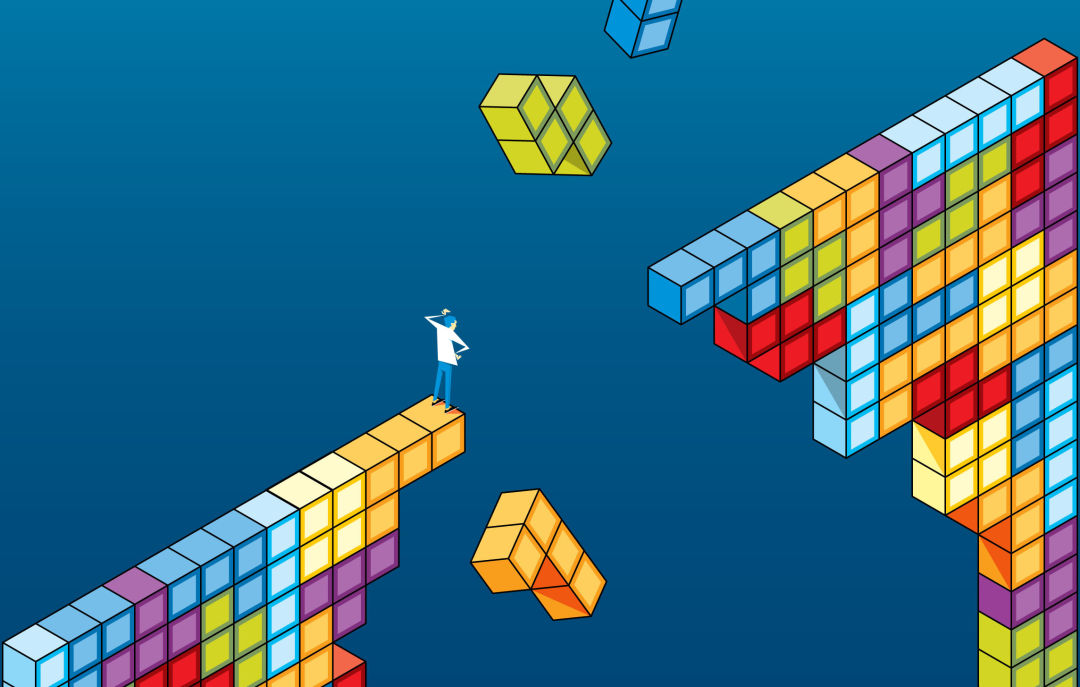

Image: Martin Gee

Terry Purcell just died. Perhaps sensing my silent disappointment, he starts a new game. The blocks begin to fall again, raining down from the top of the boxy, ancient TV. Lines build with alarming speed. This time, he’s locked in, the geometric pieces falling into line in clean succession, Purcell flipping them with imperceptible button pushes, sliding one into place as another hurtles downward at breakneck speed. I’m sweating for him.

“If you want to hone your skill, if you want to keep yourself sharp, you have to play all the time,” he says after dying on level 26, three levels before what’s known as the kill screen.

Tetris, the iconic video game invented by a Soviet-era game developer named Alexey Pajitnov and popularized by Nintendo’s 1989 version, is still a thing. The challenge of fitting together a rapidly growing pile of geometric puzzle pieces (“tetrominoes,” don’t you know) has retained a cult following and a competitive scene with its epicenter in retro-loving Portland. Since the competition moved from LA in October 2012, the world’s greatest Tetris players have come to the Convention Center to duke it out in the Classic Tetris World Championship. But no Oregonian has ever claimed the title.

Purcell, a former high school teacher, thinks he might have a shot. Now 35, he was a teenage Tetris whiz, once clocking a whopping 851,000 points, a single-game score that would earn him a spot on the championship leaderboard even today. He came back to the game after seeing Ecstasy of Order, a 2011 documentary that chronicled the first championship.

“It was this thing that we all struggled with in our basements alone, and never knew [others like us] existed,” he says. “There were me’s all over the country!”

There are three major rites of passage for Tetris players on their path to greatness. First, to “max out,” or to beat the game with a score of 999,999. The “max out,” says Adam Cornelius, a Portland-based Tetris fanatic and director of Ecstasy of Order, is “the ultimate video game white whale.”

“There are certain records that humans feel built to break,” says Purcell. “Like a 10-second hundred meters, a four-minute mile. [The max out] feels like that. It’s a perfect record. It’s just within our capability.”

After you’ve harpooned that Moby Dick, the challenge is to max out after starting the game at the staggeringly rapid-fire level 19. After that, all that remains is to win a world championship. And that’s where Purcell is setting his sights.

“It’s sort of like the mental equivalent of running a 100-yard dash for five minutes straight, five times in a row,” says Cornelius of the five-round tournament, noting that the final round can last up to 40 minutes. “Most people want to just make it fit together, but you have to be okay with the chaos. To really be good at it, you have to think past your desire for order. You have to live in the chaos effectively.”

Purcell as audience member (top) and competitor during the 2015 world championships

For five of the championship’s six years, an LA-based Tetris savant named Jonas Neubauer has claimed the crown. Watching him play is an adrenaline-filled spectator sport in and of itself and not for the fainthearted. He is, says Purcell, a Tetris artist, painting impressionist masterpieces while his competitors stack blocks like so many engineers. He builds messy walls, leaves ragged gaps, and creates seemingly unworkable patterns, only to knock them all down with the ease of a master and just a hint of a smile on his face. That style would lead to certain death for lesser players.

“It’s so brutal—for Jonas to win five out of six times, it’s absolutely insane that he hasn’t messed up,” says Cornelius. “The level at which he controls the game is unfathomable.”

To try to compete, Purcell recorded videos of his practice games. Students in his high school history class followed his trajectory closely—they made a ringtone of his anguished scream when he missed a maximum score by one error—and baked him a cake when he finally scored the max 999,999 points in January 2014.

“I was a voracious consumer of anything Tetris from the time that I saw the film,” he says. “I was watching videos of anyone I could, I had flash cards, I had all kinds of study strategies that helped me.”

His dedication also brought on what’s known as the Tetris effect: when the game’s seven shapes make their insidious, insistent way into your life. “I would see cars coming at me and I would envision them as pieces,” he says. He still has trouble looking at the corner of a shelf or a table without mentally fitting a piece around it.

But he’s willing to risk student mockery, the Tetris effect, and more if it will help him unseat the champion. Two years ago, Neubauer knocked Purcell out of the semifinals, and he left in third place, the closest he’s come to the crown. This year, he’ll also go up against a Japanese Tetris grand master and the European champion, who hails from Finland. And it will all be decided before hundreds of fans at the convention center.

“Every tournament I’ve played in, he’s beaten me,” says Purcell, who recently quit his Beaverton teaching job to move to Eugene. “I want to win.”

“In front of 400 people gasping and clapping, you’re playing this game where if you push a button wrong for a millisecond, it’s over,” says Cornelius. “These guys deserve to be famous.”