The Battle of ‘86: How Oregon’s Last Great Election Came Down to One Fatal Mistake

[Editor's note: Norma Paulus died on February 28, 2019.]

F

rom her apartment in Portland’s South Waterfront, Norma Paulus can watch the Willamette River on its restless slide through Oregon. On rainy afternoons, the slate river is all business. On sunny mornings, each ripple throws off sparks.

For Paulus, though, every day brings fog. Photographs on the wall show her with presidents of the United States, senators, even Bono and Muhammad Ali. She tells a story about each photo, pauses, then repeats the stories again and again. Sometimes the tales come out the same. Other times, details slip beneath the surface, beyond her reach.

At 83, Paulus struggles with dementia, but she recalls one thing clearly. “I could have been governor of Oregon,” she says. “I should have been.”

Thirty years ago, Paulus prepared to make history as the first woman to hold the state’s highest office. She promised to continue the narrative of Oregon as an environmental trailblazer, a progressive state that carefully planned for its future. A former state rep and two-term secretary of state, Paulus was heir to Oregon’s tradition of liberal Republicans. No one in state politics rivaled her for stature, experience, and popularity. The governorship was hers for the taking. Everyone knew it.

But Oregon had just been through dark times. In the early 1980s, a calamitous recession had wrecked the state’s primary industry, timber. In 1982, the unemployment rate had hit 12 percent. In some rural counties, one of every six workers was without a job, the worst unemployment since the Great Depression a half century earlier. The recession hollowed out small towns and smashed middle-class dreams, and many families who had cut their living from the Oregon woods for decades fled or splintered.

The recession exposed Oregon as an economic colony, too reliant on outside forces. In Salem, dumbfounded political leaders shrank in stature as Oregon’s financial problems grew. The next governor could face years of woe.

But 1986 also held great promise. As governor, Paulus could lead Oregon into a modern economic world and remake the state for generations to follow. As the stakes facing Oregonians grew, so did her sense of destiny.

And then the one person who could take it away from her—the only Oregonian who could match Paulus for reputation, recognition, and ambition—entered the race.

As Portland mayor in the 1970s, Neil Goldschmidt had snapped the city out of a stupor and led its downtown revival. The Democratic star had delivered for the state’s biggest city what Oregon as a whole now needed—energy, urgency, change. He had been out of politics for five years, holding a comfy job at Nike. Decades later, Oregonians would learn that Goldschmidt also spent his political heyday working to cover up a horrifying secret. At the time, however, he shined as the Democrats’ most promising, talented political figure, and his declaration to run for governor seemed to underscore the election’s importance.

Today, what we want are candidates who stand as tall as the challenges we face. We rarely get them. Oregon votes blue, and lopsided statewide races often come down to a not-a-hope-in-hell Republican running against a Democrat who wins without breaking a sweat. But in 1986, Paulus and Goldschmidt delivered. The two best candidates in a generation waged a fierce debate over Oregon’s future, matching each other step by step until the campaign’s final days. As political drama, it was Oregon’s last epic.

And even with so much on the line, the 1986 race for governor turned on the vagaries of luck, timing, and hubris. A single stumble could still change everything—for the future of a state, and for one woman’s life.

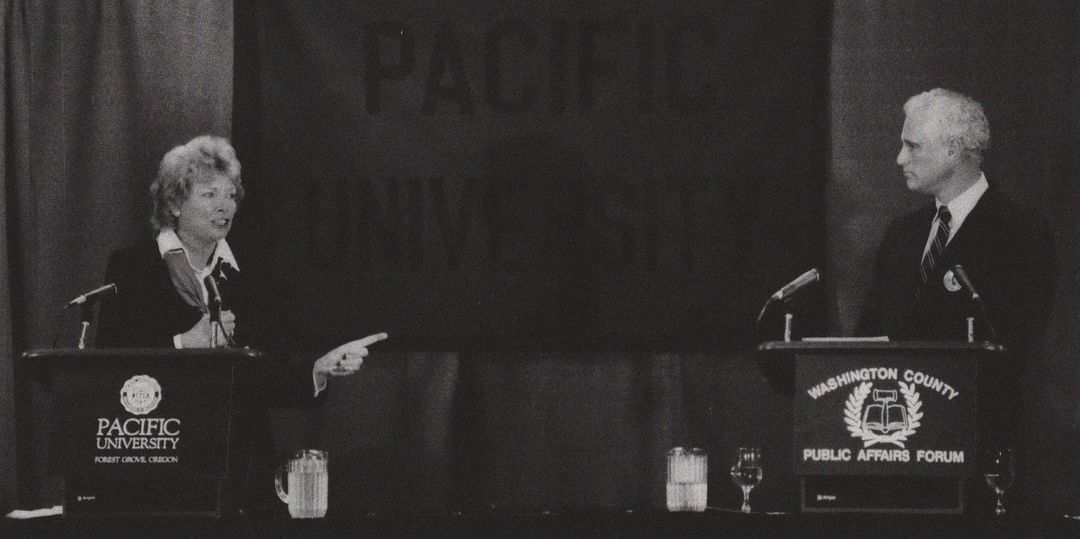

Republican nominee Norma Paulus (above, left) and Democratic rival Neil Goldschmidt debated across a state buffeted by recession.

Image: Courtesy The Oregonian

Late September, 1986: I walked into Al’s Big Y Barber Shop in west Eugene, just across Highway 99 from the Zip-O-Log mill, where a short pile of Douglas fir trees blackened in the rain. I was working for Willamette Week, covering a big political campaign for the first time. Paulus and Goldschmidt were in town that night for a televised debate, and I figured a barbershop across the road from a mill was an ideal place to get people talking about the sorry state of Oregon’s economy.

It was nearly closing time, and Al, the shop’s owner, was counting the money from the till. He looked at me with a mix of impatience and hope. He wanted to go home, but here I was, some kid who badly needed a haircut. Maybe there was another $5 in his day.

He pointed to a chair. No, I told him, I was a reporter, writing about the race for governor. What did he think of the candidates?

Al was voting for Goldschmidt. Why? Because of Goldschmidt’s promises to fix the economy? No, Al said. He’d known Neil when the candidate was a little boy. He’d even cut his hair.

The only customer in the shop—a thick, toothy man getting a buzz cut from another barber—could go one better. Turns out he’d grown up in Burns and went to high school with Paulus.

I’d gone into Al’s looking for quintessential quotes I could slot into a story about economic despair. Instead I got a powerful lesson about politics in the state: Oregon was one big small town. The state had 2.7 million residents then (compared to 4 million today), as interconnected by its back roads as its freeways. A natural politician like Norma Paulus played well. You could toss a fir cone in most Oregon towns and hit someone who knew her. For well more than a decade, Paulus had worked main streets, high schools, and banquet rooms across Oregon. To some, it seemed as if she’d always been running for governor.

Born in Nebraska, Paulus was raised in Burns and wielded a compelling bio. She overcame polio at 19, won admission to Willamette Law School without a college degree, and established herself as a successful appellate lawyer. She won an Oregon House seat in 1970, and in 1976 she won election as secretary of state, a traditional jumping-off point to the governorship.

Oregon’s voting rolls had historically been dominated by Democrats. And yet for decades the GOP won most statewide races. Oregonians wanted politicians to be conservative with their tax dollars but open-minded about how to fix problems, a combination that gave rise to a distinctive brand of politician: the charismatic, liberal Oregon Republican. As a young legislator in the 1950s, Mark Hatfield fought to end racial segregation; later, as governor and a US Senator, he opposed the Vietnam War. Tom McCall, a former TV newsman, forged Oregon’s environmental identity as governor in the ’60s and ’70s. Paulus traced the same path, championing progressive causes, especially equal rights for women. She was engaging and quick-witted—steelier than most of the male politicians she outshined. And she claimed to understand Salem better than anyone, prompting her favorite boast, “I know where the bones are buried.”

For many, she gained heroic status in 1984 by preventing a massive voter fraud. An Indian guru, Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, had founded a commune in Wasco County. His followers bused in thousands of homeless people, aiming to pad the election rolls and take over county government. Paulus used her secretary of state authority to halt the scheme.

Still, Paulus—seeking to replace the outgoing governor, Republican Vic Atiyeh—believed her gender worked against her. “Our polls showed 10 percent of voters would simply never vote for her because she was a woman,” says Ron Saxton, an adviser to Paulus who ran as the Republican nominee for governor in 2006. “She had a headwind from the start.”

Paulus could also be biting and sharp, intending to be funny but with unintended results. She once suggested Oregonians toss rocks at any car with California plates crossing the state border. (She later said she was joking.) People close to her wondered if she could be disciplined throughout a long, difficult race.

“She loved the quips—and she loved them too much,” says Foster Church, who covered the 1986 campaign for the Oregonian. “Her comments often came off as too cute. And maybe that was her downfall: she would get carried away with her own wit.”

Paulus wanted a high-minded campaign. She especially admired McCall, who 20 years earlier won the governorship against Democrat Bob Straub. Straub and McCall spent the campaign trying to one-up each other as to who was the bigger environmentalist. McCall’s victory had ushered in a doctrine of livability above all else, manifested in pollution curbs, the Bottle Bill, and statewide land-use planning. Protect Oregon, McCall argued, and prosperity will follow.

But in 1986, Oregonians wanted a buttoned-down, pinstriped savior, someone who could walk into corporate boardrooms and walk out with new jobs for the state—now. Goldschmidt fit the description, standing in the glow of Nike, the Beaverton-based global giant that soared on its Air Jordans.

Goldschmidt had been raised in Eugene, a star high school basketball player who attended the University of Oregon and then UC-Berkeley for law school. As a legal aid lawyer in Portland, he ran for city council in 1970, campaigning against an entrenched city hall. Portland had never seen anything quite like him—energetic, relentless. Two years later, at the age of 31, Goldschmidt won election as mayor.

Under Goldschmidt, Portland’s downtown came back to life. He empowered neighborhoods that had felt trampled by city hall. The most notable change was the plan for a controversial light-rail line from downtown Portland to Gresham—a tradeoff won when local activists halted state plans for a new highway through the heart of Southeast Portland.

He also brought another big advantage: campaign experience. Paulus had run statewide, but against forgettable candidates whom she easily kicked aside. But Goldschmidt had won tough races, including a 1976 mayoral reelection bid against City Commissioner Frank Ivancie that was a block-by-block street fight. He later spent 16 months as US transportation secretary under Jimmy Carter—an undistinguished tenure that nonetheless showed Goldschmidt how politics were played at much higher level.

But Goldschmidt worried many voters. He was a creature of Portland, and that could be political poison in other parts of the state. It’s not that Goldschmidt was out of touch with rural Oregon—he’d never been in touch. His aides at the time saw the problem as the candidate’s urban otherness. Goldschmidt knew his candidacy made voters outside of the state’s biggest city uneasy. “They wish,” Goldschmidt said at the time, “they didn’t have to vote for someone like me.”

The campaign opened with its narrative in place. Paulus was the favorite to win, running with the slogan “The leader you know. And trust.” Goldschmidt was still trying to tell the difference between Waldport and the Wallowas. In August, Goldschmidt made it worse for himself as the two campaigns argued over where and when to hold debates. He wanted a debate in Portland close to Election Day. Paulus wanted an earlier debate in Bend. Goldschmidt complained to a Portland TV reporter that he didn’t want to debate Paulus “in the middle of nowhere.” His press secretary, Ginny Burdick, recalls that she nearly threw herself in front of the TV camera when her candidate said that—but the damage was done.

Goldschmidt claimed he meant the “middle of nowhere” on the calendar, not the state map. But many rural Oregonains believed he’d simply revealed his true attitude toward any place beyond Portland city limits. Goldschmidt at first refused to apologize, but caved in to his staff’s demands. A pained Goldschmidt went to Bend and read a scripted mea culpa in a public square for TV cameras. A Paulus supporter stood behind him with a homemade sign, “Welcome to nowhere, Neil.”

In early September, both candidates appeared in the Pendleton Round-Up parade, an age-old opportunity for Oregon politicians to show their cowboy bona fides. Paulus rode a horse, as she did every year. A Round-Up newcomer, Goldschmidt got laughs—not the good kind—as he waved from a buggy. The Oregonian had just published a poll showing Paulus with an eight-point lead. Goldschmidt later said the Pendleton appearance was his lowest point of the campaign and “the worst hours of his life.”

Many big statewide races feature two or three debates. Paulus and Goldschmidt faced off seven times, evenly matched in substance and punch. Even so, voters looking for daylight between their stands on the issues had to squint. Both wanted to revive the comatose timber industry, get tough on crime, give schools more money, and protect abortion rights. In the Eugene debate in September, the moderator slipped and introduced Paulus as “Norma Goldschmidt.” Goldschmidt and Paulus laughed and embraced as if they’d just been declared husband and wife.

But the moderator’s goof underscored the dilemma both candidates faced. My colleague at Willamette Week, Jim Redden, nailed it with his analysis at the time. “After a more than a year of full-time campaigning,” he wrote, “the candidates still seem too much alike. Their joint slogan might be, ‘Experienced, Competent. Interchangable.’”

“We had to take risks,” says Burdick, the Goldschmidt press secretary who has since gone on to serve in the Oregon Senate. “We had to do something that made us stand out and to show we were moving forward.”

Goldschmidt put out a campaign document called “The Oregon Comeback,” 112 pages of generalities about reviving the state’s economy. Voters began telling pollsters they believed Goldschmidt would be better at creating jobs. “I had practically every CEO and captain of industry in Oregon backing me, not him,” Paulus says today. “They knew I could do the job. But too many people simply couldn’t see a woman being better at business than a man.”

Paulus relied on her established image as an honest and trustworthy leader, offering few new ideas. “She had one card to play,” says Floyd McKay, then a news analyst for KGW-TV, who later worked as Goldschmidt’s spokesman. “And she had already played her card.”

Goldschmidt also got lucky: The Portland-to-Gresham light-rail line had been under construction for years, and critics—including Paulus—portrayed it as a boondoggle. But the line opened in September 1986, proof of Goldschmidt’s innovation. Meanwhile, he tagged Paulus as part of the “same old Salem crowd.”

He also got better as a candidate—sharper, tougher, more comfortable talking to people outside of Portland. “Neil had played in the big leagues and could get his answers down to short sound bites,” says Paulus campaign aide Jim Carlson, now a lobbyist in the state capital. “Norma’s answers turned more lawyerly. She was more a creature of Salem.” And he ran a modern campaign. His early TV ads accused Paulus of proposing $100 million in new spending with no way to pay for it. (The Democrat blasting the Republican as a big spender: a different era.) One ad mocked her claim that she knew where “the bones were buried” by showing someone digging one deep hole after another and turning up nothing but dirt.

Paulus’s out-of-state media consultants created tough ads that hit back at Goldschmidt. One showed a grainy, spinning image of Goldschmidt’s face, portraying the Portlander as a flip-flopper willing to say anything to get elected. “The ads worked,” says Bob Moore, Paulus’s pollster. “They tested well. People came away not wanting to vote for Goldschmidt.”

She didn’t like them. In early October, Paulus summoned her campaign staff, friends, and family to her house to watch the ads. Her professional consultants urged her to air them. She shook her head.

“I’d rather lose this campaign,” Paulus told the group, “than run a negative race and win.”

At about the same time, a poll in the Oregonian showed that Goldschmidt’s ads had done their damage. The race was now dead even.

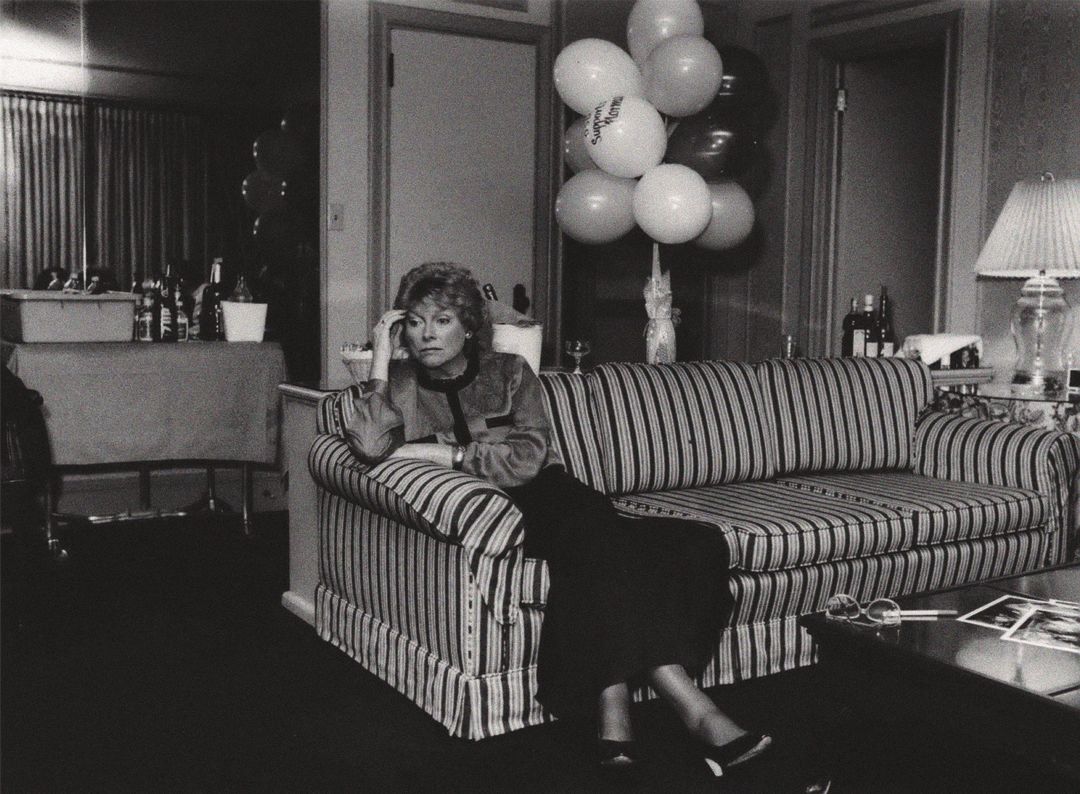

Paulus struggled to differentiate herself from Goldschmidt, who presented himself as the face of change and painted her as a Salem insider.

Image: Courtesy The Oregonian

Paulus felt it all slipping away, and her lack of campaign experience wore on her. She obsessed about every detail, staying up past midnight, pushing herself harder than ever. Impatient and exhausted, she convinced herself she had to land a knockout blow to Goldschmidt at an October 15 debate at Willamette University in Salem, her home turf. Instead, Goldschmidt rattled Paulus by accusing her of having supported legalization of marijuana and prostitution in the past.She fumbled for answers, and never came close to hurting Goldschmidt.

As Paulus left the stage, shaken by her debate performance, reporters rushed in. What about marijuana and prostitution? Did Goldschmidt get the better of her? In a moment of bravado, Paulus said she wasn’t at all caught off guard. She’d known in advance Goldschmidt would come after her about marijuana.

“I have a mole in his campaign,” she said.

Her claim was stunning. Campaigns often try to pry inside information out of the opponent’s operation, but few candidates ever go so far as to admit having a spy. What made the moment even stranger was that there was no mole. A few days earlier, a woman had called the Paulus campaign, claiming her boyfriend worked for Goldschmidt. She wanted Paulus to win, so she was passing on what her boyfriend told her about Goldschmidt’s debate plans.

Campaigns get tips all the time—some reliable, some not. What prompted Paulus, in the glare of the campaign, to claim she had a “mole”? Paulus later told her staff that she had wanted to lash out at Goldschmidt after the Salem debate. She thought she might get under his skin by making him think his campaign had a leak. For a brief moment she had forgotten herself, and she hadn’t considered how her message aimed at Goldschmidt would play out in public.

“Boy,” Paulus says today, “I really screwed that one up.”

At first, her comment went largely unnoticed. But the Oregonian’s Church, preparing a Sunday column, called her back the next day, and Paulus repeated her claim. When he opened that Sunday’s paper, Goldschmidt’s pollster, Tim Hibbitts, couldn’t believe the gift Paulus had offered up, and he urged Goldschmidt to strike back fast and hard.

“I said this plays against her image,” Hibbitts says. “This was not who she made herself out to be.”

By that evening, Goldschmidt called Paulus’s supposed planting of a mole in his campaign “sickening.” The next day, Democratic Secretary of State Barbara Roberts and Portland City Commissioner Mildred Schwab denounced Paulus during a press conference that got lots of play. Goldschmidt had cleverly stretched Paulus’s words—she’d never said she planted a mole in his campaign, just that his campaign had a leak. Paulus tried to explain herself, but there was no pulling any of it back. The story continued to roll out over the next week. As one Oregonian headline put it, “Paulus stuck in ethical ‘mole’ hole.”

Her poll numbers plunged eight to 10 points. “That’s when the dam broke,” says Moore, Paulus’s pollster. “She ran as the clean, honest candidate, the one you could trust. With one comment she stripped away the veneer and looked just like every other politician.

“And when that happens,” Moore adds, “voters look for something else: who would be better for Oregon’s economy.”

With two weeks before Election Day, a desperate Paulus aired the attack ads she had earlier disavowed. “Norma knew she was going to lose,” Saxton says. “And she never, ever blamed anybody else.” Her numbers ticked upward, but it was too late.

The campaigns’ pollsters, Hibbitts and Moore, say today that Goldschmidt had momentum before the “mole” comment and probably would have won the election anyway. But Saxton, Paulus’s campaign aide, says Goldschmidt himself saw it differently. Years later, he says, Goldschmidt confided that Paulus had proven more resilient than people knew.

“If the campaign would have gone on another week,” Saxton recalls Goldschmidt telling him, “Norma would have won.”

In the end, Goldschmidt beat Paulus by 42,000 votes out of 1 million cast.

The most important governor’s race in modern history did not give Oregon its comeback. As governor, Goldschmidt achieved only a few successes. In 1987, he got voters to approve a school safety net that kept districts from closing for lack of funding. And he convinced business and labor to agree on workers’ comp reforms. Beyond that, his administration was often a distracted, unfocused jumble. In 1990, he cited his divorce from his wife, Margie, as the reason he would not seek a second term.

Today, Oregon is still trying to erase Goldschmidt from its memory. In 2004, Willamette Week revealed that, as Portland mayor, Goldschmidt had repeatedly raped a 14-year-old girl, a neighbor in Northeast Portland. Goldschmidt, who was then making millions as a consultant and fixer, admitted to the crime, which by then was too far in the past for him to face charges. He dropped out of the public eye, and his portrait in the capitol building was taken down, as if his time as governor had never happened.

Goldschmidt declined to talk for this story. But he told me in a letter, sent in May of this year, that he has at least one regret about the 1986 race: that he and Paulus never found a way to become closer allies. After the election, Goldschmidt offered Paulus any job in Oregon government that she wanted. She took Goldschmidt up on his offer and asked for a seat on the Northwest Power Planning Council.

Paulus never shook her bitterness toward him. “I had hoped this might lead to a closer relationship with her,” Goldschmidt wrote in his letter. “But she wasn’t looking for it as part of the appointment and it never happened.” And she never got over her defeat. “She has shouldered it as her own responsibility,” her son, William “Fritz” Paulus, says. “She lost on her own terms.”

Three decades later, the battle between two rival progressives stands out as a hinge in Oregon political history—the end of one era, and the beginning of now. After Paulus’s loss, the Republican Party made a hard turn to the right—and over a cliff. As the Portland metro area vote became larger and more progressive, Republicans pushed ever more strident and conservative candidates. Since 1986, Oregon has seen 41 statewide partisan elections, including those for US Senate. Democrats have won 34 of them, including all seven races for governor. They currently hold every statewide office and both legislative chambers.

Paulus later served two terms as state schools superintendent. In 1995, she made a run for the US Senate seat vacated by Republican Bob Packwood, sent packing after his own sex scandal. She lost in a crowded GOP primary to Gordon Smith, a conservative state senator from Pendleton. Once her party’s best hope, Paulus won only one of every four votes cast.

In 1999, her husband, Bill, a prominent Salem lawyer, died. Four years ago, Paulus was diagnosed with dementia. In September, she moved from her apartment with the river view to an assisted living facility.

Paulus knows she can no longer recall many details about 1986. But she can still feel her way along the edges of memory, and flinches at the sharp edges of what remains.

“I wanted to be governor,” she says. “So did a lot of other people. I let down a lot of people who worked very hard for me.”