Meet Judith Arcana, a Pioneer of '70s-Era Underground Abortion Work

In the summer of 1970, Judith Arcana’s period was late. Three weeks late.

She did not welcome the prospect of pregnancy: the 27-year-old Chicagoan had lost her high school teaching job a few months earlier, and she’d recently separated from her husband. She called a medical student she knew.

“I’ll never forget these words,” Arcana says. “He said, ‘Everybody here says, Call this number and ask for Jane.’”

The number connected her not to one woman but to a clandestine group, “Jane,” that carried out thousands of abortions from 1969 to 1973, when the procedure was still outlawed in most of the country. Part spy ring, part pop-up clinic, Jane depended on dozens of dedicated women.

As it turned out—“after the latest period in human history”—Arcana wasn’t pregnant. But after several hours on the phone with a Jane volunteer, she decided to stop by an orientation session at a church just two blocks from her apartment.

“They seemed so cool,” says Arcana, who’s now 75 and has lived in Portland for more than 20 years. “Serious about life—grown-up and smart.” Arcana, with her middle-class Jewish upbringing in the Great Lakes region, had never envisioned herself a radical. “Never in a million years,” she says. “My stepmother actually said to me, ‘You used to be such an ordinary girl. What happened?’”

In the ’60s, terminating a pregnancy was a crime in almost every state—in Illinois, felony homicide. (Oregon legalized abortion in 1969.) Women often turned to a crypto-medical netherworld: midwives, doctors, dangerous back-alley quacks. In 1969, Jane hoped to change that for Chicago women.

It was a time of civil rights marches, antiwar protests, and student radicalism. Chicagoans had witnessed brutal violence between police and protesters at the 1968 Democratic National Convention. “That was the atmosphere that in a sense allowed—if not prompted—women of a political turn of mind to understand that the system was never going to be of service,” Arcana says. “We had to take our lives into our own hands.”

Officially called the Abortion Counseling Service of Women’s Liberation, Jane began as a referral service, connecting pregnant women to physicians willing to perform abortions. Members put up posters on college campuses, ran ads in radical newspapers, and handed out pamphlets at nascent women’s lib groups. “Pregnant? Don’t want to be? Call Jane.” (Today, similar language sometimes advertises crisis pregnancy centers—anti-abortion outfits, often run by conservative charities.)

Callers left messages on an answering machine, a novel technology for the time. The so-called Janes counseled each woman: They explained the technical steps of the procedure—information not readily accessible in a pre-internet age. More loftily, they spoke of abortion as a way for women to take control of their lives.

On the day of their appointment, women first reported to “the Front,” typically an apartment belonging to a friend of a Jane. Volunteers then transported clients to a different location, such as a motel room or another apartment, where a doctor performed a surgical abortion or induced a miscarriage.

Janes checked in with women afterward: did the doctor seem sloppy? Drunk? Did he come onto you? Did he demand extra money? (Abortions could run $500–1,000; at the high end, that pencils out to more than $6,000 today. The service kept a loan fund, and members, themselves mostly white and college-educated, sometimes haggled with abortionists to drive down the cost.) These questions, along with the pre-abortion counseling, fulfilled the service’s broader mission.

“There was a whole feminist philosophy behind it,” says Johanna Schoen, a Rutgers history professor who studies women’s health and reproductive rights. “They saw this procedure as transformative for women, teaching them that they could be in charge of their own lives and their own bodies. That was something very particular to Jane.”

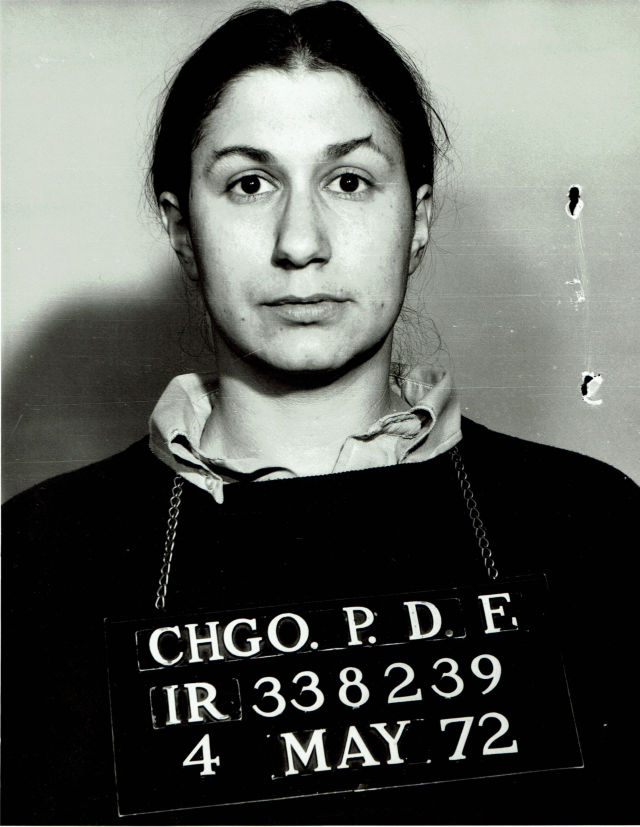

Judith Arcana on a road trip in Colorado in 1970

Image: Courtesy Judith Arcana

When Arcana joined in autumn 1970, Jane arranged about two dozen abortions a week, according to a history of the service by Laura Kaplan. In the same book, Arcana describes working at the Front—where women often arrived with children, other family members, or friends in tow—as “being a stewardess with a radical feminist consciousness.” Janes served tea and coffee, plus milk for the kids.

“It sounds so corny, but the job was really to comfort folks,” says Arcana, who is garrulous and wry as she leans forward to make points. “People who were waiting for a woman to return, sometimes they would ask, ‘Do you think hers will be an easy one? Or a hard one?’ That’s a question I remember being asked more than once.”

Then, in early 1971, it emerged that one of Jane’s abortionists wasn’t actually a physician. Some Janes seethed. For others, it was a sign: “Wait a minute, don’t you see what that means?” Arcana recalls. “If he can do it, we can do it.”

Rather than booting him out, the Janes enlisted him as an instructor. A handful of members learned to perform D&Cs (dilation and curettage, in which the uterus is scraped out) and induce miscarriages. They made other changes, too. Doctors had often insisted patients wear blindfolds to protect physicians’ own identities; the Janes scrapped that. They dropped the price to $100, or whatever a woman could pay, and ditched cheap motel rooms for their own apartments. Sometimes, that meant asking a husband to take the kids and the dog and skedaddle for a few hours. At one point, the service rented a two-bedroom apartment. Each morning, a few Janes boiled the instruments, made up beds with brightly patterned sheets from the Marshall Field’s bargain basement, and laid heavy plastic on top. In the event of bleeding, they grabbed ice trays from the kitchen and placed them on the woman’s belly. No women are known to have died while in care of the Janes.

Arcana remembers inducing and midwifing a number of miscarriages, including for a 15-year-old who miscarried in the living room of Arcana’s apartment. Arcana taped plastic bags to the carpet. After, she drove the girl home, to her parents’ house. She asked to be dropped off several blocks away. “You know what I mean?” she asked Arcana, who answered, “Yes, I know what you mean.”

As the Janes were putting back-alley abortionists out of business in Chicago, women across the country were questioning and reshaping medical practice and health care in their own ways. The 75-cent, 193-page pamphlet that would become Our Bodies, Ourselves was published in 1970, and so-called self-help groups sprung up to help women—with the assistance of a speculum, flashlight, and mirror—look at their own cervixes. (When Arcana had a child in 1971, she remembers letting him play with a plastic speculum. “Like a duck,” she says. “For him, it was a toy—clack, clack, clack.”)

Arcana took a maternity leave from Jane in early 1972. (“We espoused the belief that women should have abortions when they need them and babies when they want them,” she recalls.) On her first full day back, a Wednesday in early May, Arcana was working as a driver, shuttling women between the Front in Hyde Park and a South Shore apartment building. As she and a client stepped off the elevator, a few police officers stood before them. They flashed their badges: detectives from the homicide squad.

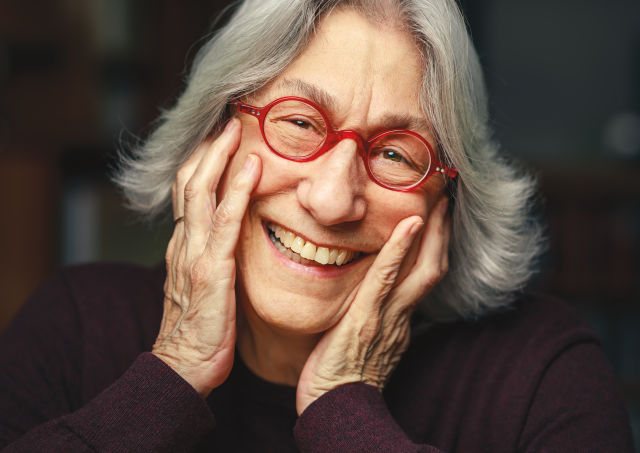

Arcana after being booked in May 1972

Image: Courtesy Judith Arcana

Arcana, arrested along with six other Janes, spent the night in lockup. In her mugshot, Arcana’s long dark hair is parted in the middle and tied back. A collared shirt peeks out of her sweatshirt. She was still nursing, and had to express her breast milk into a dirty sink in the cell.

“Women seized in cut-rate clinic,” read a Chicago Daily News headline. The “Abortion Seven” hired Jo-Anne Wolfson, a crackerjack lawyer who appeared in court in a canary yellow outfit and clanking silver bracelets. (Janes who hadn't been arrested quietly resumed abortion work.) In September, a grand jury indicted all seven on charges of felony homicide and conspiracy to commit abortion. Conviction could have meant years in jail.

Then, in January 1973, the Supreme Court ruled on Roe v. Wade. Charges against the seven were dropped, and Jane dissolved.

Arcana went on to teach women’s health classes and feminist studies at several Chicago colleges. She earned a PhD in literature, taught at the graduate level, and began writing essays, stories, and poetry, including about abortion and her work at Jane. She moved to Portland in 1995 and went on to publish several poetry collections (4th Period English, about immigration, received a new edition this spring), as well as works that defy easy categorization—such as a zine that speculates about a post-Roe future. For the past two years, she’s hosted a poetry show on KBOO.

In the late ’90s and early ’00s, as research for her writing, Arcana visited abortion clinics in Portland. “The majority of the women were filled with shame,” she remembers. “I had seen hundreds of abortions, but I had never experienced that before. [At Jane] people were embarrassed to have messed up. There was fear because it was illegal, or because it was a medical procedure, or because people might disapprove of the sex. But there was not an attitude that this was murder.”

These days, Arcana is busy with several films about Jane: she was a consulting producer on a microbudget indie called Ask for Jane, and she’s advising on a potential project starring Elisabeth Moss. Her son—the very one who played with a speculum as a toddler—is producing a new documentary about the group.

Arcana today, in her home in Northeast Portland

Image: NASHCO PHOTO

This cinematic mini-boom, Arcana says, reflects America’s current reality. Ninety percent of US counties lack an abortion clinic. Many states require waiting periods or ultrasounds. In March, Mississippi adopted the nation’s tightest abortion restrictions, and Republican-dominated legislatures across the country are considering comparable measures. Many women still rely on abortion access funds for financial assistance. Oregon has some of the most progressive reproductive health policy on the books, but next door in Idaho, state health insurance doesn’t cover abortion, so women often travel to Oregon or Washington for care.

Before Roe, Arcana says, abortion rights supporters could articulate a moral argument. After Roe, they mostly abandoned talk of morality.

“That was a terrible political error,” Arcana says. “If you’re going to make a person, you have the responsibility to give it a good life.” Because at its core, she says, “abortion is a decision about motherhood.”