Miranda July in Conversation with Portland Novelist Chelsea Bieker

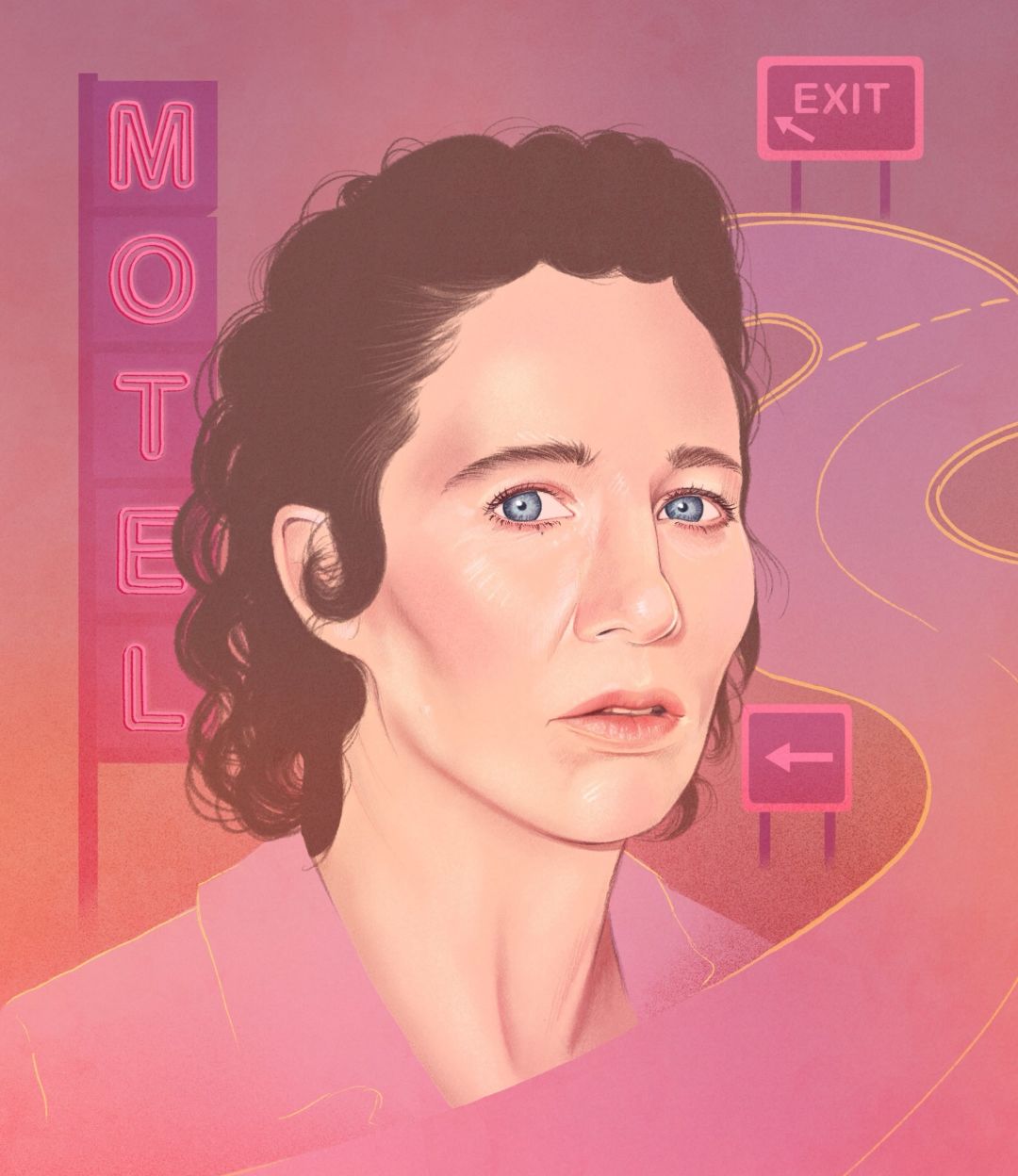

Image: Becki Gill

Today is no ordinary day for Miranda July. The morning we talk over Zoom happens to be her first in a new home in Los Angeles, the renovations of which have kept me glued to her Instagram stories for months. Of course they have. July has that rare ability to tap into our innermost feelings, to make a Facebook Marketplace search for a new rug feel vulnerable and layered with intention, even desire.

Maybe I’m projecting. After devouring the 50-year-old’s latest novel, All Fours, it’s hard not to see everything through July’s magic lens. The book is narrated by a woman who, amid the hormonal shifts of perimenopause, recalibrates her systems of family life, art-making, and sex by way of a solo, cross-country road trip sans husband and child. At least that’s what she tells them she’s doing. All Fours feels like a conversation with a close friend. Nothing is off topic or taboo—inexplicable yearnings, birth trauma, existential questions we fear voicing even to ourselves.

July got her start in the Portland post–riot grrrl scene in the ’90s, making short films and performance art, while I was a preteen in Fresno, California, dreaming of the alternative universe she was busy creating. My affair with her work began in 2005, with the film Me, You, and Everyone We Know, which won the Caméra d’Or, Cannes’s prize for debut feature directors. Her 2007 story collection, No One Belongs Here More Than You, strengthened my affection; her 2015 novel, The First Bad Man, rearranged my mind.

With All Fours, she returns to avenge past generations, excavate funny little feelings, and play with the tension between her own identity and her characters’. “Why not just give her no name?” she told me of the book’s unnamed narrator. “And when it comes to a job, I’ll leave it open-ended enough that you can slot in my career, if you want to.”

Chelsea Bieker: Thank you for writing about perimenopause. I’ve only become aware of the term in the past few years, which feels like a crime, considering I’m rapidly approaching it.

Miranda July: In my early 40s, I started having conversations about it with my friends, who I should say are some of the smartest women on Earth, and yet we were all so dumb about this topic of our bodies. My impulse was to perform the magic trick of writing a novel [about it] and have it be really, really informative. But I didn’t know how to put it all together. Then a book came out called What Fresh Hell Is This? about perimenopause that kind of says all the things. And there was an article on the front page of the New York Times Magazine called “Women Have Been Misled About Menopause.” And it was like, “Oh, it’s happening.” So what can a novel do? I realized I could have perimenopause be seen through just one woman’s eyes. I decided we’re far enough along—we’re not really—that I can have a character who doesn’t do it perfectly.

There was a precision, something about the very quality of this transition…. I’m suggesting that it might be profound in the way that finding yourself and your calling is in your teenage puberty years. If we lived in a matriarchy, it might be understood that [perimenopause] was a powerful time that everyone would be aware of and give room for.

CB: Early in All Fours, the protagonist remarks on “that funny little abandoned feeling one gets a million times a day in a domestic setting.” I think it’s exactly that funny little feeling—about desire, about the parameters of domestic life, and about aging—that snowballs in the book. It’s not nothing; it’s not to be ignored.

MJ: While writing, I had to pause many times and think, “or is this nothing? Is this just me looking where I shouldn’t be looking, putting attention where it shouldn’t be?” With a line like that, the thing that made me write it down was a feeling of recklessness, like I’m pointing at a thing and calling it out. I really did, for the first couple of years, [worry that] the whole topic was, like, not graceful.

[Before writing the book], the main option I saw, in terms of aging, was to be vague and graceful about it. But what reward was I going to get for doing that? All I could come up with was that maybe I would be ignored less meanly. And that didn’t seem like a very good prize. [laughs] I think I’ll take my chances—maybe the conversations with other women that could come out of the book would be a better thing to have.

CB: The book follows a woman as she ditches a plan to drive across the country, secretly renovates a motel room in the next town over, and pursues a romance with a young Hertz rent-a-car employee—all while her husband and child assume she is on her way to New York, crossing one state line after the next. It felt like she had to invent a material space where she could act on the newfound desires (sexual and relational) of this perimenopausal, transitional time, because those experiences could never really happen in a domestic—

MJ: —yeah! How do they happen?

CB: But that yearning for them to happen.

MJ: Right, and they can’t just be in your head.

CB: Did you always know the motel room would be a main setting?

MJ: When I started writing the book, I said to my partner—now I call him my coparent—I said, “The best time for writing for me is first thing in the morning, and we know that’s not possible in this house with our kid. And what if I spent one night a week, Wednesday nights, in my studio.” I said, “I’ll wake up and write, then pick our child up from school Thursday afternoon.”

So that was similar but different to what happens in the book. It was ostensibly for the book. But if I went out to dinner with a friend Wednesday night, just knowing that I could come home whenever I wanted…. The reentering of this different self probably was the biggest work I needed to do for the book. That was the starting point of so much.

I’d be in my studio fantasizing—because there’s a house behind this house; there are two houses on the property—about renting both of them. I imagined redecorating and making this compound where I worked here and lived back there. I didn’t know how; obviously I live in a house with my family. But I will tell you, you’re seeing me on the first morning of the first day of having woken up in that back house.

CB: That’s incredible!

MJ: And on Saturday night my kid will join me, and I’m madly getting everything ready. And it’s just a few—it’s walking distance from the house that I did live in for [the past] 20 years.

CB: Wow. I have chills.

MJ: And so, yeah. That’s, yeah.

CB: I’m asked all the time about what in my fiction is real, and what is not. And I always revert to this line, which is actually something Ann Patchett quoted her mother saying: “None of it happened, and all of it’s true.” It feels like the best explanation of how my “real life” filters into my fiction. Because there is overlap—how could there not be? But I’m more curious how you feel about that question.

MJ: I’ve really made that problem worse by being in some of my movies. Since I made it uniquely difficult to make that separation, [I thought], “Why not kind of play with it?” Like, yes, it’s fiction. All kinds of things happen that didn’t happen. But why not be extra confident about it? The thing we’re not saying is that men aren’t conflated with their work in the same way, and [this question] can divest women of our actual fiction-writing abilities.

CB: The narrator is haunted by her grandmother Esther’s suicide, who—at least the narrator’s father says—killed herself because she lost her looks, over gray hair. That family lineage weighs heavy and has such a strong effect on how the narrator carries herself. How did that facet come about? Did you always know it would be such a presence?

MJ: I will say, that part’s true. In a way it’s my dad’s story more than mine. But nonetheless, I’m the living woman in that matrilineage. This has informed my sense of getting older as much as anything. Issues of aging, of course, are going to be tied to our parents and their parents. So I didn’t feel there was a way to be honest in that territory without landing there at points.

I shouldn’t talk about this. It makes it, um, too personal. But I did feel like I was avenging them, in some ways, by writing this book. Like, I’m so sorry that it wasn’t better. I’m going to try to do something that feels reckless, but isn’t fatal, that gives and doesn’t just take away.

CB: I’ve found that each book I write has something to tell me. I think I know what I’m doing, what it’s about, and then they turn around and say, “Actually, this is what I’m here to tell you.”

MJ: I was talking with my best friend, Isabelle, who this book is dedicated to, about nervousness around ways the [book release] could go wrong—backlash, or, I don’t know what. And she said, “Well, the book has already changed your life; you changed your whole life because of the book, with it as a companion.” And my life is literally different—in a different way than the narrator’s, but it worked on me. And so she was like, “You’re kinda safe.” I’ve sort of landed on a shore that’s right for me. Meanwhile, there’s also this book that can now be in other people’s lives.

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.