In 1964, Portland Tried to Crack Down on the City’s Gay Scene. Here's What Happened.

"The Unmentionable People are virtually untouchable people and they are growing stronger each week.”

June of 1964: Doug Baker, the Oregon Journal’s city gossip columnist, held forth under a caricature of his own cigar-gnawing mug. The Unmentionables proliferated. Their lairs numbered eight, maybe even 10. Portland’s afternoon paper, zestier and more, eh, populist than the larger, duller Oregonian, was on the case.

Baker reported: “A veteran police officer said last week, ‘Either they’re growing in number or I’m just seeing a lot more of them.’” The unnamed sources kept coming: a Portland State student propositioned by another woman; a “businessman” vowing “vigilante” action. Baker noted the cops traditionally took a “hands off policy with respect to the Unmentionables.” Now, though, matters grew more serious.

“[T]hese biological rejects cling tenaciously to the myth that they are, in some strange way, something special,” the newsman typed. “It’s time the mayor’s office had a new look at this old problem.”

Portland had been a relative oasis for (as we might say now) the LGBTQ community. Clubs and bars did a quiet business. In public, people “wore the mask.” Queer politics barely existed. But in 1964—as national politics simmered in the heat of a presidential campaign pitting Lyndon Johnson against right-winger Barry Goldwater—a shifting culture and a conservative town’s establishment collided.

Today, June’s Pride celebration is a decades-old civic tradition. As George Nicola, a longtime activist and historian for the Gay and Lesbian Archives of the Pacific Northwest (GLAPN), notes, the local power structure embraced equality long ago: “Since Bud Clark was elected in 1984, every mayor has been gay-friendly.” The city elected its first gay mayor in 2008. An out bisexual Portlander serves as Oregon’s governor; an out Portland lesbian, as state Speaker of the House. Rainbow flags fly everywhere. It’s almost impossible to imagine queer Portland in the shadows. (Almost, but given certain ideologies prominent in national politics, not quite.)

Five decades and more ago, it was a different town.

“There was no organization,” Nicola says, “and everything was very closeted.” Progress was basically subterranean. By the early 1960s, Rich’s Cigar Store stocked ONE and the “homophile” Mattachine Society’s Review, decorous political magazines published out of Los Angeles and San Francisco, respectively. (Customers asked at the counter.) In the years after World War II, a small crescent of welcoming spaces evolved along our rainy streets. Some dated to the ’30s or before; many flickered in and out of existence according to the usual whims of business, culture, and real estate. A few works of scholarship document this lost world, notably the online GLAPN archives and a 2004 Oregon Historical Quarterly essay by historian Peter Boag, readily accessible online.

The Rathskeller, on SW Taylor Street, developed a reputation by the ’40s; in roughly the same era, women seeking women gathered at the Buick Café, at SW 13th and Washington. (Boag’s article quotes a 1949 police report: “These women were recently ousted from San Francisco for their actions and are ... confirmed Lesbians.”) By the early ’60s, the scene (as surveyed by a GLAPN tour of historic sites) included the lesbian-friendly Milwaukie Tavern and the gay-male-oriented Tel & Tel on SW Oak.

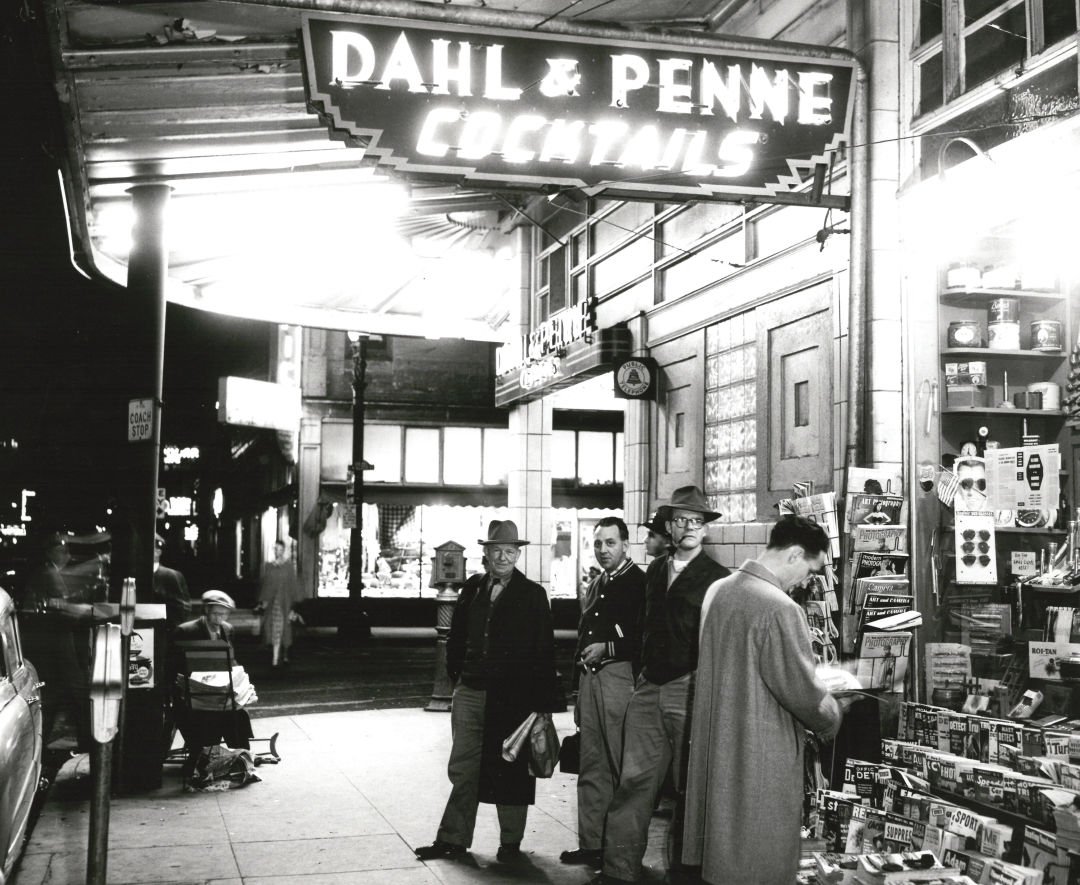

Walter Cole, best known as Darcelle XV, remembers the early ’60s, a few years before he founded his now-iconic drag club in Old Town. “The bars were flourishing,” the 87-year-old stage legend recalls. Cole notes the Dahl & Penne Tavern, on SW Second just off the Morrison Bridge; the GLAPN archives memorialize a late-night scene there starting around 1962. The archive records Other Inn as Portland’s first leather bar, launched in ’64 on SW Alder between Second and Third.

“The door would open and, whoever you were, you just walked in,” Cole says. “The police and officials just left them alone—there weren’t raids or that sort of thing.”

The Harbor Club stood out: prominent and, perhaps, notorious. “Dark and busy,” Cole says of the bar on SW First, a worn relic of the 19th-century waterfront. (The navy once declared it off-limits to sailors ashore.) “Mysterious,” Cole continues. “Everyone went to the upstairs bar, and you wouldn’t know it was there from the street. We didn’t have a flag then, you know. Anything in the world went on in there.”

The bars, as now, needed licenses from the Oregon Liquor Control Commission. For that, they needed city council’s endorsement, which had rarely been a problem—until the fall of 1964.

The Dahl & Penne, home to a pioneering mid-1960s drag show and late-night scene

Image: Courtesy The Oregonian

Oregon police made a series of arrests for various sex and pornography offenses in 1963, which triggered a classic media panic, with Oregonian headlines like “They Prey on Boys.” Portland’s mayor, Terry Schrunk, decided the time had come for action.

Schrunk reigned as mayor for 16 years, somehow bridging the Eisenhower era, ’60s tumult, and the early ’70s. By 1964, he had already survived a racketeering scandal that led to a US Senate investigation and a trial in which US Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy testified against him. Boag classifies Schrunk, a Democrat, as a “breadwinner liberal,” favoring benevolent big government—for traditional households and citizens only.

By ’64, Schrunk had launched a Committee for Decent Literature and Films (!), and heated rhetoric swirled in city council meetings. Boag’s OHQ article culls some transcript gems: the police testified of women who “caress, kiss and fondle each other in public” at the Model Inn. Most riotously, 1 a.m. at the Harbor Club saw a huge crowd “packing it, with standing room only. From then on, all activities, such as males openly kissing each other, fondling each other, with no attempt to cover these activities.”

Schrunk and the council decided this would not stand (though one commissioner astutely noted that “these people are not going to disappear”). After a series of hearings in November and December, the city moved to shut down six bars, pressuring the OLCC to revoke their licenses.

“Everyone was shocked,” Cole remembers. “This was not how things had operated.”

James Damis was a young attorney, representing the Tel & Tel. “The owner bought it knowing it was a gay bar,” Damis, now 82 and still practicing law, recalls. “He ran it clean. He didn’t permit any hanky-panky.” The city’s move struck Damis, and other attorneys representing bar owners, as patently discriminatory. “I remember saying, ‘You can’t do that,’” Damis says, “and one commissioner saying, ‘We’re the city, we can do anything!’ Well, no.”

Damis and other attorneys pressed their arguments to the liquor commission. “We said it’s clear that this recommendation from the city is not because of any activity going on at the bar,” Damis remembers. “It’s simply because gay people congregate there. And that’s not constitutionally permissable.” According to Boag’s research, some attorneys involved in the situation cited the just-passed Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The denouement, then, was classically Portlandian: no billy clubs, no bold riots in the streets, just two rival bureaucracies and a well-framed legal argument. The unlikely agent of progress: the OLCC, which essentially dismissed the City of Portland’s attempt to crack down on “the Unmentionables” out of hand.

“I was surprised the OLCC had the guts,” Damis says now. “But they did.”

Schrunk sputtered. He wrote the governor, who ignored him. The only casualty, in the end, was the Harbor Club. When the city pulled its food license, the waterfront redoubt shuttered.

By 1967, nobody cared,” Cole says, of the year Darcelle XV opened in Old Town. “Gay bar. Lesbian bar. Drag bar. No one cared. By then, it was pretty open.”

In one odd (arguable) byproduct of the 1964 episode, the Portland bars’ survival may have muted activism. “In other cities, it was constant harassment,” Boag says. “In Portland, after 1964, the bars were left alone, and as a result Portland gays tended to be more lethargic politically.” We never had a Stonewall.

George Nicola notes that Portland’s first formal LGBTQ political organization, the Gay Liberation Front, didn’t organize until 1970, and arose from correspondence in a small alternative newspaper, Willamette Bridge, not any confrontation with The Man. Throughout the ’70s, as progressive bastions across the nation adopted both symbolic and actionable antidiscrimination measures, Portland and Oregon tended to move slowly. But quick or slow, it got better. By 1972, the Oregon Journal was running gingerly neutral stories (“‘Gays’ Here Almost Prim”). In 1977, the city formally recognized a gay pride day. (This year’s Pride Northwest festival and parade take place June 16 and 17.) Campaigns against ferociously bigoted early-’90s state ballot measures helped push Oregon politics in general onto their current progressive path.

Ironically, change came at the bar scene’s expense. The sanctuaries the city targeted in ’64 are now ghosts of the cityscape. A bank tower replaced the Dahl & Penne, where drag performers strutted before Darcelle XV; the Tel & Tel is now a social services agency. The Harbor Club’s premises now house Paddy’s, an Irish bar likely to see flush business during Fleet Week this month, no one the wiser.

“There was more entertainment—more shows and fun stuff—back then, and of course many more bars,” Cole says. “We’re down to what, five? And the reason is, we don’t have to have a bar. We can go everywhere. When you’re Darcelle, you get invited everywhere.”

Top Image: The Harbor Club—off-limits to sailors, and at the center of the 1964 gay bars brouhaha (photograph courtesy the Oregonian)