Will This Zombie Adventure Vault Oregon's Video Game Industry to the Next Level?

Central Oregon is crawling with zombies. No, not the shambling undead from ’70s B-movies you could outrun at a jog or pick off from the safety of a mall rooftop. Oregon’s zombies are social and in shape. They hunt (yes, hunt) in hordes, sometimes several hundred strong, running at a full sprint. If you get caught in the wrong place at night—feeding time for the “freakers”—good luck.

And they’re only one of the threats in Days Gone, a video game set to arrive to much fanfare on the PlayStation 4 this spring from Oregon’s up-and-coming Bend Studio. This Central Oregon is already filled with bears and wolves and bandits out to kill you. There are hyperaggressive ravens who smash windshields and extreme storms that stop a protagonist dead in his tracks. In this brutal hellscape, running out of gas on your motorcycle is a life-threatening mistake.

“One of the enemy types in the game is just the cougar,” says Bend Studio creative director and head writer John Garvin, peering eagerly out from behind a row of monitors on his desk, each showing some god’s-eye view of his digital domain. “These animals are becoming more of a threat because their habitat is disappearing. They had to kill a cougar up on the butte just last week.”

Conversations that whiplash between real life and the video game realm happen a lot when the landscape right outside your office door is your digital muse. The world of Days Gone creates a postapocalyptic version of the high desert around Bend, cougar attacks and all. At the E3 video game expo in Los Angeles this past June, journalists got access to a closed-door preview of the game: many marveled at the scale and the size of the zombie hordes. But it’s the dangerous, unpredictable wilds of Oregon that Bend Studio (and parent company Sony) is banking on to overcome gamers’ “zombie fatigue” and vault their game to tentpole franchise status. As the most ambitious—and most expensive—game made so far in Oregon, it’s a gamble. But it could also be the title that catapults the state’s video game industry to the next level.

A sneak peek at the expansive, "Disneyland" version of Central Oregon developers created for Bend Studio's upcoming Days Gone video game, including various Cascade peaks

Fun fact: one of the worst video games ever made was also produced in Bend, Oregon ... by the same studio.

That’d be Bubsy 3D for the original PlayStation, a 1996 adventure starring a bobcat named Bubsy searching for rocket parts to fix his spaceship. The cartoon-style game sought to emulate the addictive cuteness of Sonic the Hedgehog, but the reception was almost universally negative. Gaming website GameSpot called the music “annoying,” the graphics “sparse,” “ugly,” and “blah,” and concluded, “Of all the 3-D action/platform games out for the Playstation, Bubsy 3D is the least fun.” (It wasn’t hyperbole: the game’s odd control system is deeply frustrating.)

“Hey, if you don’t make the best, you might as well make the worst, huh?” says Chris Reese with a laugh. He was a programmer on Bubsy. Twenty-five years later he sits in a brand-new five-story building in downtown Bend, overseeing the action as studio director at Bend Studio. Founded in 1993 to make games exclusively for the Apple Newton (RIP), the company has ballooned from the dozen employees who labored over Bubsy 3D to more than 100 people—and it’s still hiring.

Bubsy didn’t work out, but Reese says the studio learned enough to keep going. What followed next would be the first real hit for Eidetic (as the company was then called): 1999’s Syphon Filter, a third-person spy game that involved sneaking around and taking down enemies unseen. It spawned five sequels and lured Sony to acquire the company in 2000. Next, a huge leap, when Bend Studio was tasked with creating a spin-off of the beloved, critically acclaimed Uncharted franchise for PlayStation’s mobile device the Vita. (Bend Studio’s game is considered a solid, though not stellar, entry in the series.) The development of Days Gone began about five years ago, right before the PlayStation 4 (the current generation of consoles) landed on the market. The studio saw an opportunity to level up and create a AAA title, the gaming equivalent of a Hollywood blockbuster. It would be a sort of Sons of Anarchy thing. With zombies.

Days Gone is an “open world” game—a popular format built around a digital environment without restrictions. (Think the crime-infested New York City of Spider-Man or Red Dead Redemption 2’s sprawling Old West.) Days Gone’s map traverses miles of real-world space, encompassing soggy forests to treacherous mountains—what the designers call a “Disneyland” version of Central Oregon. This region “has such a diverse environment, a harsh environment,” explains Reese. “Parts of the game map are pretty accurate. We’ve taken pieces like Cascade and Belknap Hot Springs and put it together so it makes sense for the fiction of the story.”

Though Reese and his team have jumbled up the actual geography, the wilderness is still recognizably Oregon. “One of the things that makes us different than most postapocalyptic games is that we’re [setting the action] only a couple of years in [after the apocalypse],” says Jeff Ross, the game’s goateed director. “In the game, you’re not going to find forests that have grown over all the older buildings or anything. It’s more like, ‘What would Central Oregon be like if [ODOT] didn’t fix the roads for a couple of years?’”

You play as Deacon St. John, an outlaw biker with a dead wife and a grudge. Playing nice with the Oregon locals is not exactly your strong suit. But exactly how Deacon’s story progresses is up to you. Do you go straight for the ending—or do you explore the giant map, upgrading your bike, collecting resources, helping locals, and clearing out brain-hungry hordes? It’s up to you.

The game is a major play in the roughly $108 billion international industry. A recent estimate judged the size of Oregon’s video game industry to be $100 million—growing 58 percent between 2013 and 2016. While Sony won’t reveal budget figures, it’s fair to say Days Gone represents a huge leap beyond the indie and mobile games our state is known for.

Seattle and Vancouver, British Columbia, already host big-budget video game studios, but until now, Oregon’s biggest games have been comparatively tiny. Mobile games like Mayday! Deep Space and Monsters Ate My Birthday Cake are easy to download and have seen measured success. (Those old Oregon Trail games? They came out of Minnesota.) The state’s most high-profile win so far is Fullbright Company’s coming-of-age mystery Gone Home, which raked in multiple “Game of the Year” awards and has sold more than 700,000 copies since 2013. High-budget games like Days Gone do sometimes flop—Sony has, somewhat worryingly, delayed the release date multiple times and some writers who’ve had access to early previews nitpicked lackluster gameplay—but if Bend Studio can land this new franchise, it could signal that Oregon can produce both lovable indie projects and corporation-backed mega-titles.

FROM LEFT: Art director Donald Yatomi at work on Days Gone in Bend Studio’s downtown Bend office; a menacing still from the game

“Days Gone is a big deal for the Oregon [game] industry. It’s a beautiful game and has every opportunity to do well,” says Peter Lund, the gaming rep for industry advocacy group Technology Association of Oregon (and the chief operating officer at SuperGenius, an Oregon City game outfit that often produces 3-D models and props for AAA titles). “It’s hard to say what it will mean for [the state] in the long term. Oregon attracts people who have stories to tell and care about telling them well. That’s why our indie scene is so vibrant. If Days Gone is successful, it would make sense for Sony to consider other ways to leverage Oregon’s development power. More attention from big developers is good for Oregon’s industry.”

Back in IRL Bend, it’s still winter 2018—and bracingly cold. Inside Bend Studio’s office, though, it’s a pressure cooker. Everyone, Reese and Garvin included, is playing the game for hours at a time. A large, darkened room is packed with headphone-clad QA testers riding motorcycles around this digital dystopia, sneaking into abandoned saw mills, and shooting zombies in the face. They silently scribble notes on bugs they find or how to make the environment even more dangerous, more real. Every square inch has been explored, fussed over, and perfected. For now, Bend Studio is in control. That is, until they unleash the most terrifying horde yet: the players.

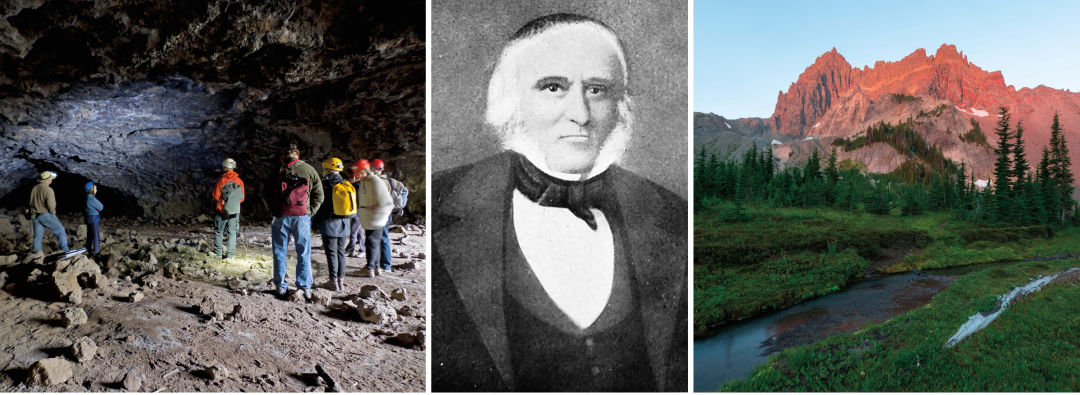

FROM LEFT: Lava tubes, Peter Skene Ogden, and Three Fingered Jack

Scene Stealers: Day Gone's Real Central Oregon Locales

Lava Tubes

The world of Days Gone is vast, open, and frequently breathtaking. But there are multiple settings where claustrophobia and darkness prevail. Modeled after the region’s actual lava tubes (created from hot lava running underground from Mount Mazama and cooling from the outside in) the in-game analogs are geologically true to form. But unlike the lava tubes at the Newberry Volcanic National Monument, these versions are a lot scarier. “Large groups of freakers—300 or 400—hibernate in them,” explains Bend Studio creative director John Garvin

Dark Lore

Players can collect “historical markers” spread throughout the map; bits of lore from Oregon’s pioneer past. “They’re all authentic. One of my narrative designers put a lot of research into this,” says Garvin. “We really wanted to explore the dark underbelly of Oregon, like ‘This was the cave where a guy was experimenting on Native Americans,’ or ‘This is where a real-life massacre occurred.’ Peter Skene Ogden was the first white explorer to come through central Oregon. There’s tons of stuff around here named for Ogden. But he was a real bastard.”

Small Towns

No, Bend does not exist in the game. It focuses on re-creating more rural environments and smaller communities like Marion Forks and Camp Sherman. (“Right now the biggest town we have is quite a bit smaller than Bend,” says Garvin. “We have a place called Farewell, though, because Bend used to be called Farewell Bend.”) What does exist: ski lodges, mountain resorts, and golf courses. Other surprises? Ross is tight-lipped. “There’s one place in the game that is singularly Oregon,” he says. “We can’t discuss it, but when it comes out you’ll know what I’m talking about.”

Mountains

Look above the tree line and you’ll probably spot a familiar sight: maybe Mount Bachelor, Mount Washington, Three Fingered Jack, or the Three Sisters. “Those are our Central Oregon mountains. They’re very iconic,” says game director Jeff Ross. “The locals [who got a preview of the game] were just thrilled.” Those peaks aren’t just background décor. “One of the things that we use them for is defining the world,” adds Garvin. “They provide beacons or landmarks for getting around because the world is really, really big.”