A Century Ago, Portland's Elite Were Obsessed with the Occult

In 1920, there were three essentials for every modern Portland home, according to the Oregonian: “a percolator, an electric iron, and a Ouija board.” It was the Progressive Era, when women gained the right to vote, child labor was called into question, and the first food safety regulations were enacted. And Portland—a spiritualist hotbed where grocery store tycoons subscribed to reincarnation and congressmen’s wives hosted séances—was in the midst of full-blown Ouija Mania. Ordinary people had Ouija tournaments to compete for most ghosts contacted. Respectable Portlanders, claimed the papers, became Ouija fiends and landed in insane asylums, and two prominent local doctors went on the record to talk about the psychology of Ouija. It was, you could say, Portland’s first great era of keeping it weird.

While Ouija was a national phenomenon, the spirits of departed Americans seemed to take a particular liking to Portland, where the city’s elite and middle class already championed arcane beliefs. (In 1908, Portland mayor Harry Lane even enacted laws prohibiting the explicit use of occult powers for obtaining wealth or procuring lovers.) Seminars on mesmerism and clairvoyance were all the rage in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and local papers ran ads for palmists, astrologers, and mediums.

And the faddish Ouija board—sold for 98 cents in the toy department of downtown’s Meier & Frank department store—brought the other side within reach for many households.

In 1890, a Baltimore undertaker and a former fertilizer salesman created the Ouija board—eager to cash in on the homemade “talking boards” spiritualists had used to commune with ghosts since the late 1840s. It found an immediate audience among grieving individuals looking to contact lost loved ones. If curiosity about spiritualism was the spark, a series of international tragedies was a can of gasoline that rocketed Ouija from spooky game to American obsession.

By the time the Oregonian touted the board’s domestic indispensability in 1920, the world was in a perpetual state of shell shock: the Spanish flu had just killed millions, the dramatic sinking of the Titanic still had the country shook, and the bodies of the Great War casualties were barely cold. Prominent Portland doctor William House wrote in 1920 for the Journal of the American Medical Association that “the world ... suffers from disarticulations resulting from the World War, and interference with functioning is painful.” House’s description of the postwar world suggests a nation adrift in a sea of PTSD.

Psychologists like House argued that during great tragedies, people were under greater emotional duress, making them more susceptible to belief in the supernatural and more easily swayed by Ouija sessions. (Perhaps coincidentally, occult motifs made a comeback in the art world in 2016.) And, at the time, few cities were more primed to accept a new portal to the great beyond than Portland.

A cover story on “Ouija mania” for a March 1920 edition of the Oregonian featured staged photos of Portland occult parties and warned that the “little toy is responsible for a large percentage of the late commitments to the Salem [insane] asylum.”

Within a few decades of its founding in 1851, Portland already had a well-established population of wealthy eccentrics, many of whom were keenly interested in the occult (see below). Grocery tycoon Fred G. Meyer was a Rosicrucian, brick baron Charles Piggott built the city’s only remaining castle, and socialite Lucy Rose Mallory was a psychic medium who led séances in the parlor of what is now Hotel deLuxe. Alt-philosophies bloomed in Portland like its emblematic roses. The Theosophical Society of Portland has been headquartered in a lavender Queen Anne Victorian on NW 23rd Avenue and Kearney since the 1950s, but the group’s presence in the city dates back at least a century. (Theosophists sought to attain divinity and understand the true purpose and origin of the universe through esoterica and mysticism. Today the group hosts meditations and lectures on topics like chakras and universal law.) Meyer’s fellow Rosicrucians, who still get together today via Meetup.com, married the “sacred sciences”—Freemasonry, metaphysics, and extrasensory perception—to Christianity. Spiritualists attempted to gain this knowledge through séances.

Local spiritualists discouraged the use of Ouija boards—arguing not that they didn’t work, but that they were unsafe in untrained hands. “We all know that matches have a use,” one anonymous source told the Oregonian, “but we do not believe in allowing children to play with them.”

But as Ouija’s popularity skyrocketed at the turn of the last century, Portland was not to be left out. In 1908, a local man claimed to have successfully predicted the weather for years using Ouija. In a one-month span, eight divorces were filed in Multnomah County due to Ouija-related woes. (One woman repeatedly accused her husband of cheating based on tips she got from her Ouija board.) In 1920, at the University of Michigan, Ouija was blamed for “extreme nervousness” in its student population. That led Joseph “Judge” Rutherford to place full-page ads in newspapers throughout the country, including the Oregonian, warning that attempting to talk to the dead was nothing short of demonism.

The local papers abounded with dark tales: the heartsick Portland woman consulting the Ouija board in an attempt to locate her missing son, only to go stark raving mad within 48 hours. The Portland man who sought business advice of the Ouija, until the voices in his head landed him straight in the asylum. In 1919, the Oregonian reported that well-known retired boxer “Sharkey” Martin was arrested in North Bend, Oregon, and held on a charge of “insanity.” He’d been dabbling with a DIY Ouija board, and became so fixated that it “caused his mind to become deranged.” One psychiatrist declared the Ouija board “nothing more than a mental murderer.”

It was Oregon, oddly enough, that countered religious and media hysteria with scientific answers. After months of startling news reports in the spring of 1920, Dr. J. Allen Gilbert of the University of Oregon Medical School (now OHSU) conducted an inquiry into Ouija.

He uncovered a rather mundane explanation: “The answers you get from Ouija are but the embodiment of subconscious states,” wrote Gilbert. In people with skills in both dissociation and ability to quickly slip into a meditative state, he explained, “the Ouija furnishes a valuable method of tapping the subconscious.”

By the end of the summer of 1920, the Oregonian announced: “City Gives Up Ouija, Studies Psychology.” That same year, the number of psychology majors at University of Oregon in Eugene was five times what it had been in 1915.

The city’s passion for the planchette may have faded, but a century later Portland still proudly touts itself as a safe space for misfits, rebels, and fringe ideas. But then again, maybe we’re just the spirits of the Progressive Era, reincarnated. Weirder things have happened, in Portland at least.

Occult of Personality: Portland's Most Notable Progressive Era Weirdos

Image: Public Domain

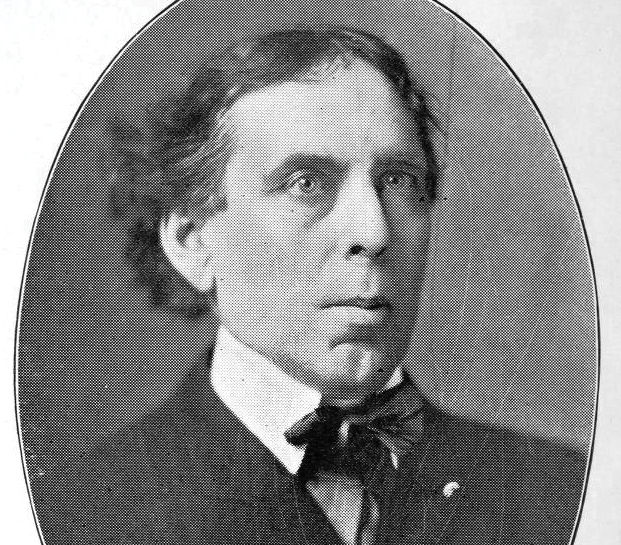

Charles Piggott

There are not enough exclamation points in the world to adequately discuss brick baron and lovable crank Charles Piggott. After losing his ostentatious home in the financial panic of 1893, only a year after completing the three-story, Romanesque Revival–style Gleall Castle, he wrote a completely batshit book called Pearls at Random Strung, or Life’s Tragedy From Wedding to Tomb. In the preface (written in first person from the perspective of the book itself!), the book declares that it should be used as a textbook in public schools. Topics include the hazards of breakfast foods, the benefits of a clean bowel, and the unnecessity of changing one’s underwear more than four times a year. A later owner of Gleall Castle—still standing in the West Hills—reported being visited by Piggott’s spirit in 1964, but a subsequent owner lamented having had no luck in summoning the ghost, not even with a Ouija board.

Image: Public Domain

Lucy Rose Mallory

Psychic friend to Portland’s social elite, Mallory was probably best known in Gilded Age Portland as the wife of Oregon congressman Rufus Mallory, for whom a Northeast Portland avenue is named, and who built the Mallory Hotel (now Hotel deLuxe). But she was also an internationally respected good vibes factory, enthusiastically espousing New Thought, or the belief in, put simply, mind over matter. She wrote and edited her own journal, The World’s Advance-Thought, in which she chronicled her experiences with astral projection as a child in the 1850s; how to shift the world’s axis through collective positive thinking; and, locally, updates on a spider she’d befriended. (Mallory wrote that after she fed it a dead fly, “it soon became very friendly, and it would eat from my hand, and run all over my head and face, and it appeared to love me.”) Leo Tolstoy was a subscriber.

Fred Meyer

Our city’s best-known grocer followed the teachings of Max Heindel, an astrologer and Theosophist who founded the Rosicrucian Fellowship in 1909. Heindel’s pragmatic tenets clearly influenced Meyer, who made time for daily mindfulness practice and based his business decisions on evidence rather than his gut—from a place Heindel called the “Region of Concrete Thought.” When Meyer died in 1978, his remains were handled according to the Rosicrucian Fellowship: his body was kept for 84 hours so that his karma-filled “seed-atom” could ascend to heaven. The seed-atom would then inhabit the head of a spermatozoa so it could enter another human being during conception and be reborn with its previous life’s wisdom intact.