Inside a School Day at the Muslim Educational Trust in Tigard

Schools are perennially noisy places. Someone is always running in the hallway or chitter-chattering in the cafeteria or busting moves in the line to the library. In kindergarten classes, kids sing songs while sitting criss-cross-applesauce on rugs; the distracted hum of students working on group projects seeps out from middle school classrooms.

But at the Muslim Educational Trust in Tigard, every Friday at around 12:50 p.m., the entire campus goes quiet and still, enough to hear a proverbial pin drop.

For the next half hour or so, the stillness is broken only by intermittent prayers and sermons. Though there are daily times set aside for prayer at the school, on Fridays families and other community members can join the students in the spacious gym, bringing their own prayer rugs, slipping off their shoes, and finding their spots on the room’s two giant carpets, a larger one for the men, and then, spaced about eight feet back, one for the women.

Space for prayers at the Islamic School of the Muslim Educational Trust

Image: Amanda Lucier

Though private Islamic schools have been steadily growing nationwide since the mid-1990s, they are concentrated in places like New York City, New Jersey, and the suburbs of Detroit, Michigan, which are home to far larger concentrations of immigrants from Middle Eastern and North African countries.

In Oregon, there is only one that goes all the way from pre-K through high school.

In a hurry

Image: Amanda Lucier

The MET campus, which houses the Oregon Islamic Academy for grades 6–12 and the Islamic School of MET for pre-K–5, is also one of the most culturally and ethnically diverse schools in the state, public or private. Students there come from 48 ethnic groups from across the Middle East, Africa, Asia, and Eastern Europe, says MET president and cofounder Wajdi Said, and speak 82 different languages and dialects.

Some are the children of doctors, professors, and engineers. Some are the children of refugees who came here with few possessions, leaving behind war-torn countries and the limbo of refugee camp life. Students wear uniforms, says programming officer Jawad Khan, in part so that any socioeconomic differences will be invisible to them. About a quarter of the school’s students receive financial aid or scholarships to help defray tuition costs, which range between about $9,500 and $10,000, depending on grade level.

A view from the hallway at ISMET

Image: Amanda Lucier

Nearly all are the children of first- or second-generation immigrants. For many of their families, the school is a haven from a more permissive public school system and culture. It’s a place where wearing the hijab—the head coverings required of devout Muslim women—is the rule, not the exception, where there is zero tolerance for violence or drugs (or phones: if a teacher repeatedly spots a kid using a phone during a class, it can be confiscated until the end of the school year), and where faith is woven into everyday lessons.

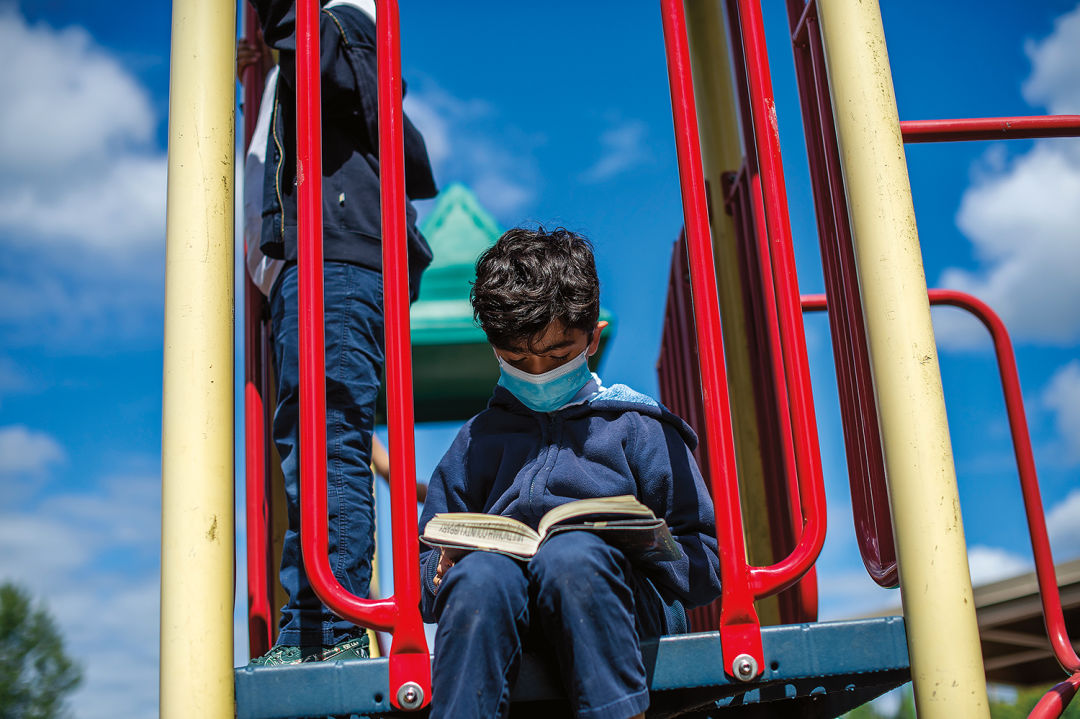

On the playground

Image: Amanda Lucier

“We believe that when you question your faith, it is a sign of faith,” says Aadil Mohamed, a Somali American who graduated in June 2022. “Here, everyone is your cousin. It’s allowed us to grow up and find our identities as young Muslims.”

Said points out that success was no guarantee. The first class of 24 K–2 students met in basement classrooms at Portland State University in 1997; by the midpoint of the school year, nearly half the parents had withdrawn their children, unsure that the new school could deliver on its promise. Two years later, the school bought its current property, then an old farmstead; overflow classrooms were housed in modular buildings. The current building held its grand opening in 2015.

Locker lingering at ISMET in spring 2022

Image: Amanda Lucier

Twenty-five years after that make-do first class in 1997, enrollment stands at about 225 students across all the grades. Typically, elementary and middle grades are the largest, though no grade had more than 25 kids in the 2021–2022 school year, and the average class size is just 15.

Though small, the school’s academic record is mighty. Its first high school graduating class in 2011 had only two students. By 2022, the graduating class was eight students strong, including one student tapped for a prestigious research internship at Oregon Health & Science University’s Phil Knight Cancer Center; college acceptances over the past 11 years have included ultracompetitive private schools like Amherst, Harvard, Cornell, Dartmouth, Middlebury, and Emory.

Learning indoors and out

Image: Amanda Lucier

Students learn Arabic and study the Qu’ran; the cafeteria, back this fall after a COVID hiatus, serves only halal food. On a recent visit to an 11th grade English class, students sat straight and alert while parsing the mood, tone, and diction in James Baldwin’s short story “Sonny’s Blues.” Older students take turns manning the attached community center’s gift shop, for an on-the-job lesson in capitalism. Holiday decorations and lights appear not at Christmas but for Ramadan, which several students called their favorite time of year for the communal nature of the celebration.

Seniors spend much of the year working on a capstone thesis project that must be presented to a panel of judges—in 2022, students researched and wrote about the “social determinants of health,” as seen through an American-Muslim lens, on topics ranging from food insecurity to what it takes to have a thriving neighborhood. Gym facilities include a swimming pool, so that boys and girls (and sometimes, after school hours, their grandmothers, grandfathers, and other family members) can learn to swim separately, in keeping with Islamic regulations. A handful of students leave having memorized the Qu’ran.

Basketball at the gym

Image: Amanda Lucier

Space and money are at a premium, but MET would love, someday, to expand the school, to add more classrooms and serve more kids, says Khan, who also serves as the school’s career/college guidance counselor. The marked immigration slowdown of the Trump administration and the pause during the pandemic have given way now to new families coming to Oregon, some looking for a school that feels like their home. There are more than 200 families on the waitlist, Said says.

“We are hoping to open an east-side campus in Gresham and maybe a Hillsboro campus in the next five years,” Said says. “There are families seeking this school. We don’t have a bus service, so our goal is to achieve equity by practice.”

Recess time at ISMET in spring 2022

Image: Amanda Lucier