Meet Portland’s Original Anti-Vaxxers

What an old-timey anti-vaxx group might have looked like (but definitely didn't)

After a winter 2019 outbreak of measles in Clark County threatened Portland’s many clusters of unvaccinated children, state rep Mitch Greenlick decided to act. With House Bill 3063, the Northwest Portland Democrat aimed to boost Oregon childhood vaccination rates by ending the state’s religious and so-called philosophical exemptions.

Not everyone agreed. As the bill sailed through spring hearings, protesters thronged the capitol steps, led by a group called Oregonians for Medical Freedom. Things took a Hollywood turn when Republicans fled the capitol to stymy a vote on a separate tax bill. To bring them back that time, Gov. Kate Brown scrapped two other bills unpopular with Republicans, including Greenlick’s.

Turns out, wrangling over vaccines is an Oregon tradition. A century ago, the Public School Protective League gathered in Portland’s Multnomah Hotel. Most members were women, putting their new voting rights to use to oppose compulsory vaccination.

At the time, the Spanish Flu and smallpox raged across the Pacific Northwest. One was preventable: smallpox, the subject of the world’s first successful vaccine. In Portland, health officials slapped placards on the front doors of flu victims, sent smallpox victims to a “pesthouse” at Kelly Butte, and pleaded with city council to vaccinate dockworkers. Officials could quarantine unvaccinated schoolchildren once an epidemic started. But they couldn’t actually force anyone to get the new vaccine.

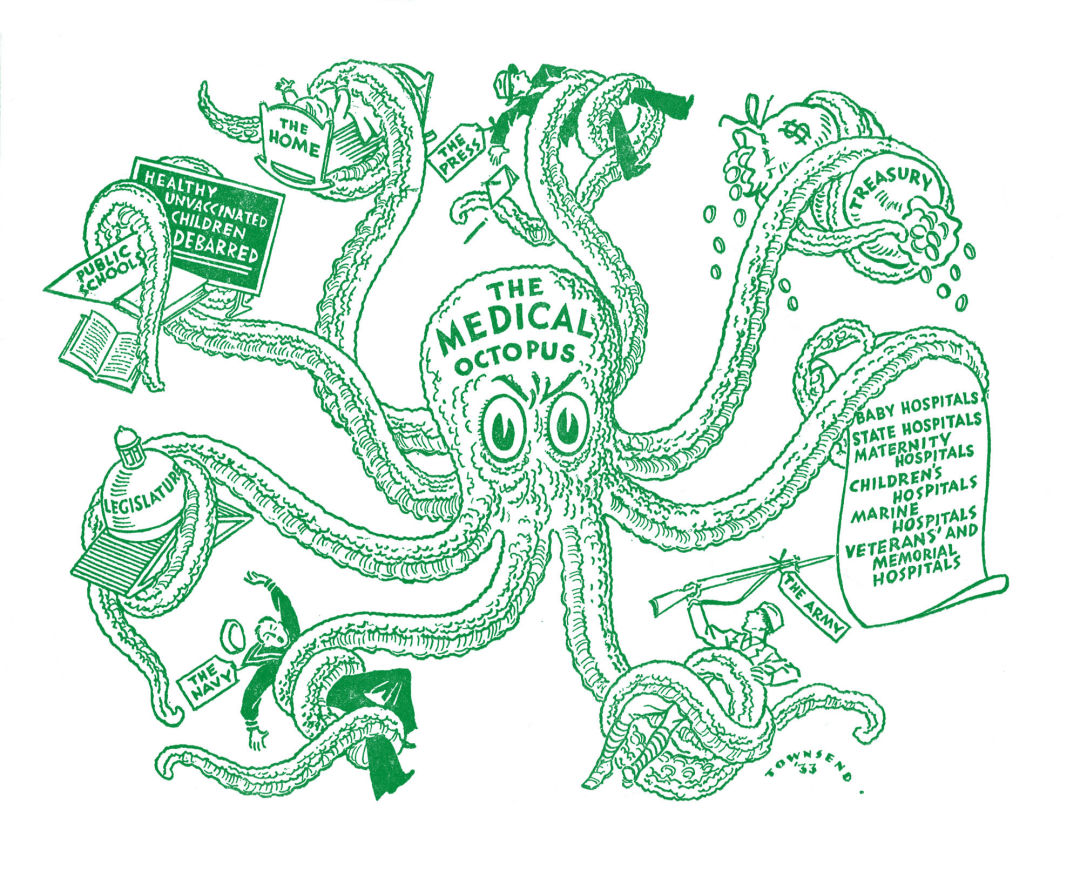

A 1933 illustration for the Boston-based Citizen's Committee Opposing Compulsory Vaccination

Meanwhile, they also battled a firebrand named Lora Little. Originally from Minnesota, Little saw vaccines as “an artificial pollution of the blood.” In 1896, she’d lost a son to diphtheria, which she blamed on the smallpox vaccine. Two decades later, she established the Little School of Health in Portland’s Mt Scott neighborhood. In debates she offered lectures in right living and rants against drugs, doctors, and the many-tentacled monster she viewed as the “state-sponsored vaccination complex,” according to historian Robert D. Johnston. In a 1914 letter in the Mt. Scott Herald, Little claimed smallpox was “life-saving” because it rid the body of “an excess of waste matter.” The Morning Oregonian was dismissive, calling Little and her supporters “crazy” and “misguided.” But that year, when the city tried to exclude unvaccinated Mt Scott schoolchildren, Little led a protest that shut the schools down instead.

Emboldened, Little went to the statehouse. She and more than 200 supporters placed an initiative on the 1916 ballot to “prohibit compulsory vaccination, inoculation and other such treatment for the prevention or cure of contagious or infectious diseases.” It failed—narrowly—and a disappointed Little left for Chicago. Four years later, her Stumptown converts tried again, with similar results.

Today, Little’s movement is vocal once more. Greenlick casts his opponents as “scientific illiterates” and members of the “lunatic fringe,” while its leaders rail against drug companies and government overreach. (Some also cite claims, long discredited, that link vaccines with autism.) At the spring rally, attendee Vicky Fivecote expressed her opposition to HB 3063.

“I am not anti-vaccine,” Fivecote told KOIN TV interviewers. “But I am ‘anti’ the government saying you have to vaccinate your child and you have to do it in this particular way.”

Lora Little would have smiled.