In Virtual School, More Oregon Kids Are Getting "Incompletes" On Their Report Cards

Teachers in the Portland metro area are giving more "incompletes" to their students in this pandemic school year.

As this most unusual of school years careens toward a holiday break, some early statistics are emerging about how the roughly 560,000 school-aged kids in Oregon, the vast majority of whom have not seen the indoor of a classroom since mid-March, are faring in a virtual learning world.

It’s tough to track, especially because Oregon’s traditional benchmarks for assessing student performance, from statewide “report cards” issued to schools by the state Department of Education to the standardized tests taken by public school kids, are on pause or pared way back this year. And the state is planning to request a waiver from the federal government for testing in English, math and science for the entire 2020-2021 school year. That means it could be years until educators and policymakers get broad, comparative data to track how the pandemic, and the move to virtual learning, has academically affected kids ages 8 to 18.

Absent that, districts are looking to student grades and attendance levels, and the news is discouraging, particularly for students from Black, Indigenous, and Hispanic/Latino backgrounds.

“In general, our students from underserved populations are struggling right now at inequitable rates, and we're working to innovatively shift our systems at every level to support them,” said Jonathan Hutchison, a spokesperson for the North Clackamas School District outside of Portland.

One strategy in heavy use by teachers around the metro area: Giving students “incompletes” instead of Fs, which gives a student more time to complete their assignments, and pull up their grade.

For example, in Beaverton, one of the state’s largest districts, 13 percent of high school students were earning failing or “incomplete” grades by the end of the first of four grading periods, the district’s administrator for secondary curriculum said during a recent school board meeting. That’s a five percentage point rise from the first semester of the 2019 school year, mostly fueled by the growth in incompletes.

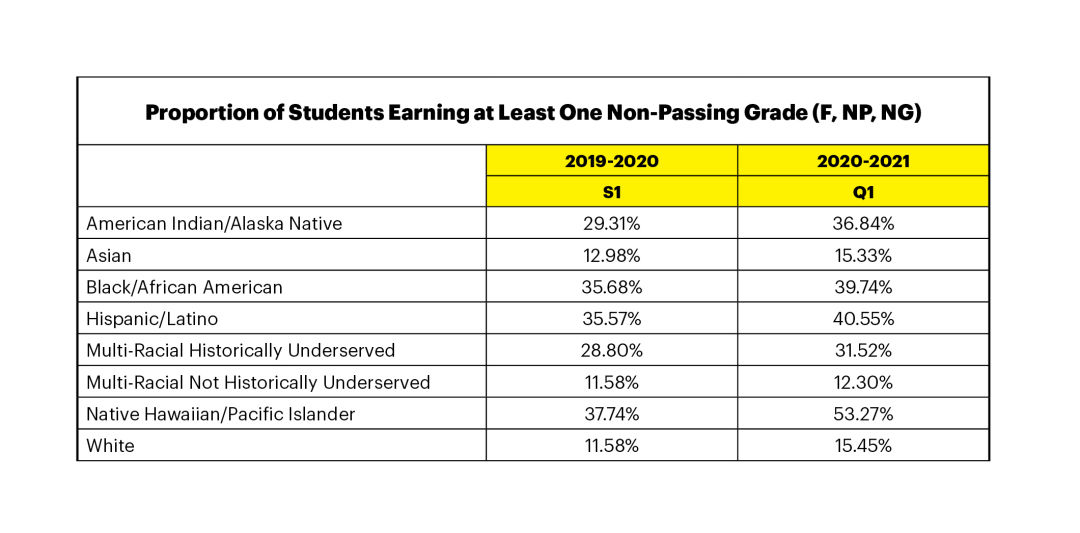

In the Portland Public School district, the state’s largest, about 5 percent more high school students in almost every demographic group across the board were earning a failing or incomplete grade in the first quarter of 2020 (from early September to early November) than they did in the first semester of 2019, which goes from September to Christmas break.

But those numbers get bleaker when it comes to historically underserved subgroups. For example, over 50 percent of Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander high school students in Portland were earning at least one F or non-passing grade in the first quarter of 2020, a rise of 13 percentage points from 2019.

It’s clear that existing education gaps are getting wider in the pandemic. About 40 percent of Hispanic/Latino and Black students received at least one incomplete or F in the first quarter this year, up from about 36 percent last year, compared with about 15 percent of White and Asian students this year, and 12 percent last year who earned those grades.

Teachers, who’ve shifted to an entirely new education delivery model, are required by the state education agency to continue giving grades, and PPS spokeswoman Karen Werstein says there’s been no grade inflation, or change in requirement for what it takes to get an A (or for that matter, an F.)

But teachers “overwhelmingly” chose to give their students incompletes, as opposed to Fs, she said, in deference to pandemic-coping students who are trying to complete their work but need more time.

Another sticky area is attendance, a real challenge when teachers cannot mandate that students turn on their webcams, given privacy concerns, and students can’t always count on a strong wifi connection and a quiet place to work.

Additionally, while elementary school students have virtual classes at least once a day where attendance is taken, middle and high school students have “asychronous” days, when attendance is measured by completing a brief assignment or checking in with a teacher during office hours.

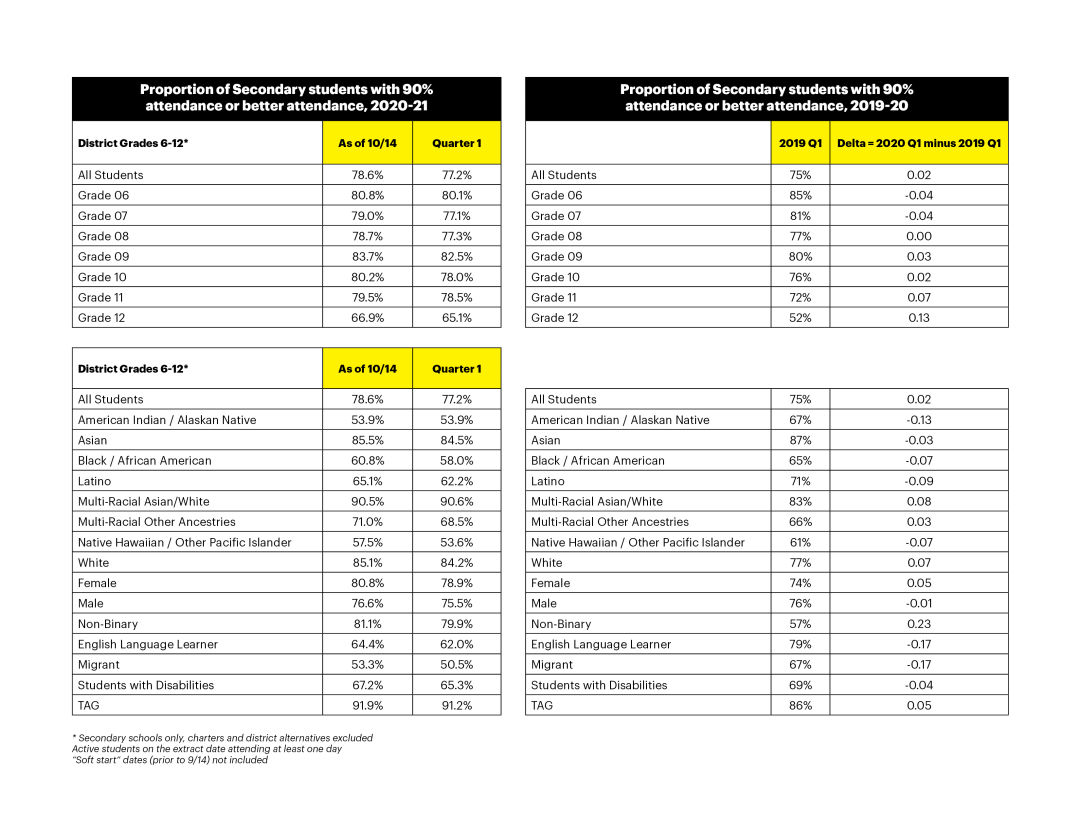

Comparing 2020 attendance data to 2019—back in the days when teachers called the roll in actual, real-live classrooms, remember?—is therefore like the proverbial apples to oranges. Still, according to PPS data, across all groups of middle and high school students, attendance actually ticked up in 2020, with 78 percent of students present for at least 90 percent of school days during the first quarter, as opposed to 75 percent in 2019.

Nonbinary students made especially large attendance gains, with 81 percent reporting regular attendance at school this year, as opposed to just 57 percent in 2019.

But there were troubling drop-offs among some groups, in particular English language learners and migrant students, whose attendance levels are way down—only 53 percent of migrant students made it to class 90 percent or more of the time in the first academic quarter, a 17 percentage point change.

Educators are racing to reach the kids who have low attendance levels and aren’t turning in assignments, Werstein says.

“In addition to synchronous (live) classes, teachers are required to hold office hours for additional student support,” she wrote in an email to Portland Monthly. “We're also utilizing counselors and social workers as well as teachers to reach out to students who are not engaging or who miss class for any extended period of time.”

Other districts are brainstorming strategies to help kids make up for lost time; summer boot camps are under discussion for Beaverton, for example, as is extending the school day when kids are able to return to campus. (Proposals like these, however, need to be paid for, and with enrollment declining in many school districts, especially at elementary school levels, it’s unclear what kind of funding Oregon schools can count on in the 2021-2023 biennium.)