The Strangest Election in America Right Now Is This Portland School Board Race

The field of candidates for the Zone 4 seat for the Portland Public Schools Board of Directors expanded and contracted with last-minute filings and withdrawals.

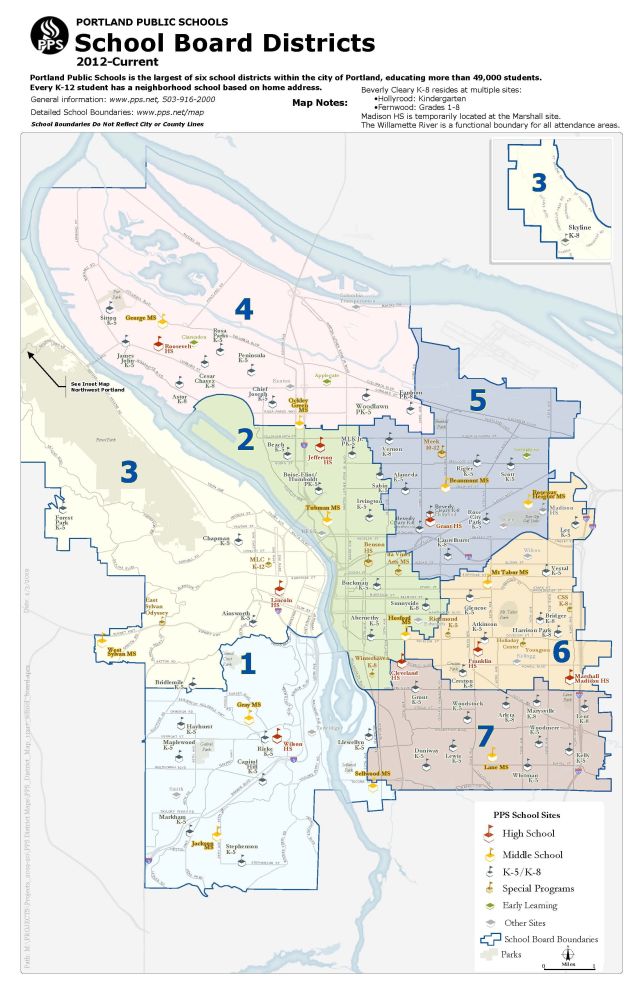

At first, it seemed like nobody wanted the job: For the first half of the 39-day filing period, no one threw their hat in for the Zone 4 seat on the Portland Public Schools Board of Directors, one of three PPS seats up for election this May. While the ballot races for two other east-side zones attracted the usual two or three candidates for the unpaid volunteer positions, Zone 4—which encompasses much of North and part of Northeast Portland north of Ainsworth—stayed blank.

Then, on March 2, with just over two weeks to go, one name appeared: Margo Logan, the GOP candidate last November for the same area’s state House seat who called herself “a Trump Democrat” turned “Trump Republican” in her 2020 Voters’ Pamphlet statement.

Logan’s entrance into the race to represent a progressive area that’s home to some of the most racially diverse schools in the district kicked some local parents and Democratic organizers into high gear. A 19-year-old joined the race a week after Logan, but he was largely ignored as election-watchers started soliciting candidates through social media and calling all possible parties to persuade them to join the race.

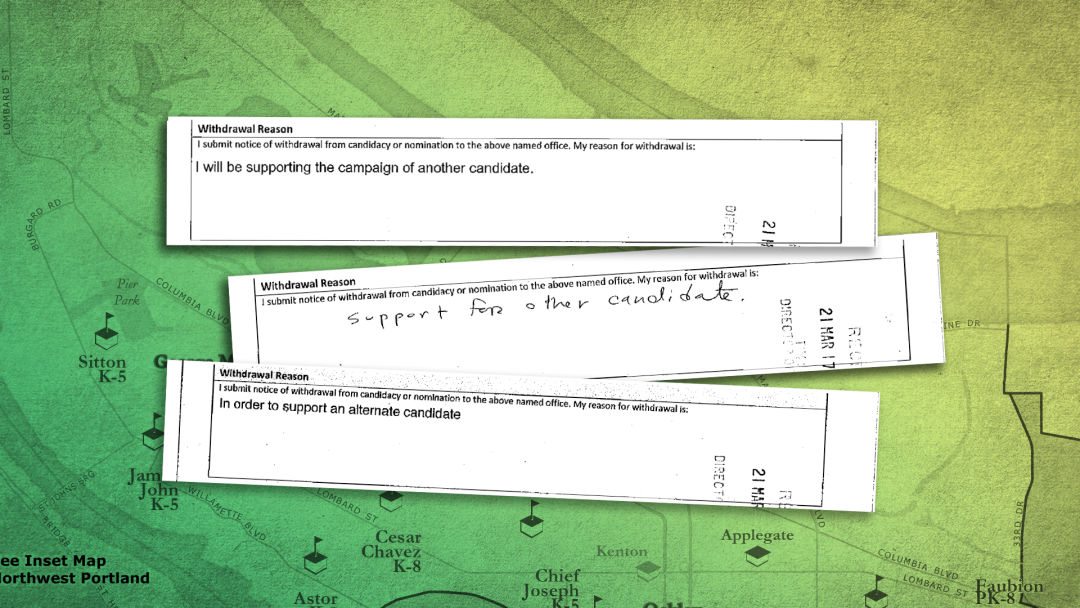

What followed was a fevered and messy clamor to enter—or exit—the race. Candidates filed only to withdraw days later, pledging to support another candidate, a Black woman, who then herself withdrew to support yet another new recruit, a Black man, only to rescind her endorsement after the filling deadline, saying she’d felt bullied. By then it was too late for anyone to hop back in, but the limited field that remained prompted someone else who hadn’t filed at all to launch a write-in campaign.

It’s not unusual for people to file and withdraw, or just not stage a campaign, in these smaller local races that tend to attract first-time candidates and others who are not professional politicians, according to Eric Sample of the Multnomah County Elections Divisions. Still, Sample says of the 2021 withdrawals, “There was a few more than is typical.”

Of those left in the race, only the write-in candidate and the 19-year-old—arguably, the two with the lowest chances of winning, according to historical precedent and to numerous poll watchers and election strategists—have said that they had the race on their mind for more than a few weeks.

What happened?

“Nobody was on top of it,” says Steve Buel, a former school board member, retired teacher, and unofficial board historian/critic. (“I’ve known all the school board members for the last 50 years,” he says. “I haven’t been very pleased.”) Buel has run for school board six times: five of them seriously, he says, and twice victoriously. On one of the serious runs, he spent up to seven months actively campaigning, working backchannels, coordinating with the teachers union in hopes of securing their crucial endorsement, laying the groundwork for fundraising in order to send out mailers to get his name in front of people for a race few really take note of.

When former board member Paul Anthony ran in 2015, “I had a very long lead-in to it—about three years,” Anthony wrote in a Facebook direct message to Portland Monthly. He’d been chair of his neighborhood association and remembers being “radicalized by PPS’s blatantly racist decision to close Humboldt School” in 2011, and he was involved in education issues through Portland City Club and the Northeast Coalition of Neighborhoods, as well as being a public school parent.

Anthony wonders if some of the difficulty in attracting candidates the old-fashioned way have to do with the aftermath of the Trump administrations, “when I think nationally the schools as a whole just tried to hunker down and survive the incompetence and toxic rhetoric.” Over the past few years, “there really hasn't been an occasion for parents to come together across school communities to advocate for systemic change or try to educate themselves about education policy,” he wrote. “And then, of course, this last year we've been shut down and locked down, just trying to survive. So people in the parent community just haven't had the opportunities to meet, talk, share, and consider how they are going to try to make things better for their kids.”

Candidates must live in a set zone, but they are elected districtwide. The seats for Zones 4, 5, and 6 are up for election May 18.

Image: pps.net

Like Anthony, Rita Moore, the current holder of the Zone 4 seat until her term expires on June 30, had been involved in PPS committees and board advocacy work long before she was elected in 2017. Moore says she decided in January not to run for a second term in May.

“I think in this moment we need more representation from people of color on the board,” she said in a phone interview March 31 of her decision to “step back and give space.” This may sound strange to those who remember that Moore, who is white, had defeated a Black woman in the 2017 race. “I thought I was the better candidate for that moment,” she says now of the issues that were facing PPS four years ago, “and this is a different moment.”

She made no formal proclamation that she wouldn’t run for a second term, but she “let it be known,” she says, after she made her decision in January. Still, some who would eventually enter the race or try to recruit others to do so say they were hampered by not knowing for sure if the incumbent was running or not.

Moore says she tried to recruit candidates for the seat—but no one she reached out to was willing to file. Yes, the unpaid volunteer gig (which required 10–20 hours or more of her time every week) is “very tough,” especially on someone who also has a full-time job. Then there’s the money and work of running: Candidates must live in a particular zone but run districtwide, which creates a more expensive and exhausting campaign. But Moore says there was an additional difficulty in recruiting candidates this year, especially the candidates of color she approached.

“I was very disturbed that many of them said they were unwilling to put themselves out there for fear of being targeted,” says Moore. “Members of the school board generally speaking are not showered with love. But there is a level of vitriol that feels new. I think it’s part of the national climate, and especially for people of color who are contemplating entering a high-visibility position. The deciding factor was ‘I can’t do this to my family. I’m afraid I might be targeted, and I’m not sure how bad it can get.’”

Michelle DePass, who won Anthony’s old seat in 2019 for Zone 2 (lower North Portland and inner Northeast and Southeast), was also making calls, doing trainings, and having conversations in the winter. “The Emerge network called through all their people of color on Zone 4,” DePass says of the group that trains Democratic women to run for office. DePass is the only Black member of the current board, serving with six white colleagues and a white student representative in a district serving 44 percent students of color.

Oregon Futures Lab, which helps identify and train candidates of color, was not closely involved in the race. In January, the Multnomah County Democrats were trying to come up with people in the area with a background in education, but they failed to find any willing candidates in Zone 4.

By the second week of March, DePass says, there was “a big frenzy” to find a candidate of color for the Zone 4 seat.

Then came Margo Logan, whose social media presence surely added to that frenzy. She’s shared theories on her Facebook page that are associated with QAnon, including the idea that Hillary Clinton is involved in child sex trafficking. Logan insists she is not associated with any group (adding that she’s intrigued by the theory that the shadowy figure known as Q might have been created by the CIA) and wasn’t recruited by anyone.

“I just saw it was open, and I learned I was in Zone 4,” Logan said in a Zoom interview on March 30. “I think public schools are on a death spiral,” she says, citing 1854 as the year things took a turn for the worse for a system intended “to indoctrinate and control,” and expressing her support for school choice and simplified curricula. (“It only takes eight weeks to learn how to read,” she offers.) She says her past experience as a substitute in some local districts showed her “an oppressive environment” packed with dysfunction and teacher stress, and she worries climate-change conversations are scaring children. She doesn’t believe her Trump support will be as big a turnoff as one might assume: “I think there are more folks from the Black community that appreciated things Trump did based on his policies.”

No matter her motivations, having Logan, a Republican many associate with QAnon, on the ballot to represent an area where Democrats outnumber Republicans nine to one set off alarm bells for many. “I can say that we worked towards proactively recruiting candidates for the Zone 4 seat (and others), and were especially motivated after hearing about the initial candidate who filed for Zone 4,” Nan Stark, a member of the Multnomah County Democrats campaign committee, wrote in an email to Portland Monthly.

A week after Logan filed, the candidate recruitment suddenly spilled onto Facebook.

On March 9, Jamila Singleton-Munson—Moore’s 2017 opponent, who no longer lives in the zone and thus could not have run—offered up her leftover campaign funds to a worthy candidate in a Facebook message posted in the N/NE PPS Enrollment Balancing Facebook group, a 4,000-plus-member, often heated forum of parents, wonks, equity activists, and more.

The next day Brooklyn Sherman, a 19-year-old Jefferson High grad, became the second person to file. He’s still in the race, and says he didn’t follow the filing drama after he put his own name in. “I’m not even running my Facebook," Sherman says. "I’m not a huge social media person.” He says that “people aren’t recruiting someone of my age” and that his interest in being on the board came from his own recent experience.

Also on March 10, former state senator and Woodlawn Elementary parent Chip Shields posted on March 10 in the N/NE group: “Anyone in North Portland/St Johns that would be interested in running for Portland Public School board?” Maxine Dexter, a west-side state rep, also started beating the bushes online.

“It all happened really quickly, honestly,” says withdrawn candidate Anna Metnick, who had heard from a neighbor and then saw on a 16,700-member St. Johns neighborhood Facebook group, where someone had shared Shields’s message, that people were hoping for an additional candidate. Metnick decided she was willing to step up if no one else was. An HR director for a nonprofit with one child at Sitton Elementary and another headed there soon, she filed her candidacy on March 12. “I’d been receiving so many emails from individuals and groups who wanted to interview me about endorsements,” she says of her brief run. “It was overwhelming.”

“I said I’d be interested in maybe talking to somebody, and then it just kind of spiraled into this crazy adventure,” says Tammy Correa, board president of the St. Johns Swap n Play and parent of a prekindergartner in Head Start. She talked to the head of the Oregon Labor Candidate School on Friday, March 12, got signatures over the weekend (an alternative to the $10 filing fee), and filed on Monday, March 15. “From that moment my life has been crazy.” By Tuesday she had a campaign strategist, though she says she’s still not entirely sure how that happened. Soon Correa was on a Zoom call with Metnick as well as Erin Brown and Brett Duesing, who had also filed to run after seeing the hubbub about the race online. Correa is Black; the other three candidates on the call are white, as are Sherman and Logan.

“I was like, let’s identify the best candidate. Otherwise we’ll just be taking votes from each other,” recalls Metnick. By the time Duesing joined the Zoom call, he later said via email, the group had “already discussed thinning the now crowded field ... and they had already coalesced around backing one progressive candidate (Tammy Correa). She already had some organization and support from groups and everybody was enthusiastic about it, so I said that was OK with me. Tammy was a stay-at-home mom, and a POC, and it seemed to me she really wanted the opportunity to be on the Board.”

On Wednesday, Correa found herself spending three hours in a photo shoot organized by We Win (a strategy group that encourages progressive candidates in smaller races), talking to current board members DePass and Moore. The whole thing “became way too much, way too fast. I started to feel I was being pushed to the forefront because I was Black,” she says. “By Wednesday I was on my second panic attack. The best way to put it, I was feeling really tokenized. Why was I the best person? I’m looking at all these people dropping out of this race because of me. Why?”

DePass says she understands the tokenized feeling: “This is what’s wrong with folks in Portland. There’s this enthusiasm, like, 'Oh my God, she’s Black!'”

While Correa was at that photo shoot on Wednesday, on the same day Brown, Duesing, and Metnick dropped out, Herman Greene, a pastor at Abundant Life PDX church in North Portland’s Kenton neighborhood whose children all went to Roosevelt High, became the seventh candidate to file for the Zone 4 seat.

Greene had been contacted by Tom Stubblefield, a retired grocer many call “the unofficial mayor of St. Johns,” after Stubblefield saw a March 9 post on Facebook in a different St. Johns community group (this one much smaller and tamer than the other) from Stephanie Blair, a member of the Multnomah County Democrats’ campaign committee, about the open seat. “Everybody was talking about it. They threw out some good candidates,” Stubblefield says of the online conversation. He reached out to three people, and says that Greene, whom Stubblefield knew from Roosevelt booster projects and the BTown Kids program, was the only one of the three who said he’d be interested.

Around 5 p.m., DePass, who works at the Portland Housing Bureau, says she got a call from a number she recognized as being associated with city hall. It turned out to be Nike Greene, director of a youth violence prevention program in Mayor Ted Wheeler’s office, who then handed the phone to her husband. “I just filed for office,” DePass remembers Herman Greene telling her over the phone. “I’m going to clear the field.” He then asked for Correa’s number and said he’d ask her to step aside, DePass says, and that he suggested to her he had fundraising and an expensive campaign consultant lined up. DePass had the impression “he was really puffing his chest up,” she says. Greene recalls the conversation differently, saying it was DePass who told him Correa was in the race and suggested he reach out.

Greene says he started really watching the race the weekend of March 13–14, when he was on a trip to California. “Nobody was there, and then it got crazy, because it went from nobody to a handful of folks,” he recalls. “Then people started saying they were going to drop out of the race. I’m like, so who’s going to be left?” Greene says he was contacted about running, and said, “Yes, I am considering running if somebody else doesn’t run. I didn’t want to be a competing force against another person of color.” He says he made a Facebook Live video to “make it real.” He filed midday on March 17, two days after Correa. “The next day I found out there was actually a woman of color in the race. At that point I was like, wow, I’m actually doing what I didn’t want to do, and that kind of bothered me a little bit.” When he and Correa connected, he says he told her, “I will never say anything that’s inappropriate or speaks down or tries to belittle.” And despite what DePass says he had told her the night before, Greene says he told Correa that “it was never part of my plan or part of this call that you would drop out of the race.”

“On Thursday morning, Pastor Greene called me,” Correa recalled a week later, and by the end of the call she had decided to drop out. She says she was persuaded that on paper, he was the better candidate. At 3:05 p.m. Thursday afternoon, Correa withdrew her candidacy. “I was like, great, he can be the Black hope,” she says. “I was not 100 percent happy with him, but I felt he’s been in the community longer.” (Correa moved to Portland only a few years ago; Greene moved here from Buffalo in 1994.) On the withdrawal form she brought to the county elections office, she had typed as the reason, “I feel that [Pastor] Greene is a better candidate. I wish him luck.”

With less than two hours to go before the 5 p.m. deadline on the last day to file, the candidates who had stepped aside for Correa were puzzled but didn’t have much time to reconsider their own candidacy. For Correa, at first it was a relief. The few days she was running, she says, “My kid was watching way too much TV, and had like four pudding cups—which would usually last a month.”

But then after announcing her support for Greene on both her withdrawal form and in the main St. Johns Facebook group, she rescinded it, saying she was not entirely comfortable with the series of events. In the meantime, Greene had secured the endorsement of local union the Portland Association of Teachers PAC. (The PAC's board staff schedules interviews as candidates file so they can announce endorsements before the deadline four days later for Voters’ Pamphlet statements.) Greene says Correa’s decision to drop out “was a mutual thing,” but that’s not the impression that stayed with Correa.

“I feel like he pushed me out,” she says. “I feel like he bullied me a bit, but I was OK to take it because I just wanted out. Waiting till the last minute was kind of a chess move so no one else could get in.”

“I feel a little bit of whiplash,” says Metnick. “I was really excited to run, and then I withdrew. And now I feel like so many things have changed since I withdrew.”

One of those changes is the appearance of a write-in candidate. Jaime Cale had had conversations with DePass and participated in some winter candidate trainings, “knowing I always wanted to be on the board,” she says. “I kept saying my time is going to be in four years, when my kids are older.” A Mxm Bloc cofounder, Cale works in the front office at Rosa Parks Elementary in Zone 4’s Portsmouth neighborhood—a job she’ll have to quit if she wins, as PPS employees are not allowed to serve on the board. Cale, who is Black and Indigenous, says as things got down to the wire she nearly reconsidered but was relieved when Correa, another Black woman she was excited to support, filed on Monday morning. “And then the week just kind of went crazy after that.”

By the time Cale learned Correa was dropping out, there wasn’t time to get down to the elections office to file herself, she says. But the now-shrunken candidate field didn't seem to have the perspective and experience she'd been hoping to see represented on the board. "I'm a graduate of PPS, I'm a parent of PPS students, and I've worked for the district, so I really feel like I know the ins and outs of how the district runs," she says, also citing her equity work and advocacy related to special education and families who wanted to keep their school's year-round calendar. The next day, Duesing’s wife, a PPS teacher who was also disappointed at the disappearance of the progressive candidate she’d been excited about, called Cale and asked if she’d ever consider a write-in campaign, Cale says. On Friday morning, March 19, the day after the filing deadline, Cale called DePass and Anthony, called the elections office to learn more about write-in votes (they’re only tallied if the write-in total is more than the number of votes for the leading candidate on the ballot, and Cale was assured that a vote for, say, Jamey Kale would land safely in Jaime Cale’s column), and talked to her family.

Cale admits there’s been no successful write-in candidate in Portland in modern history, but she thinks the smaller, off-year election might make for a lower hurdle.

“Unfortunately, only 100,000 people vote in this election in May, traditionally,” she says, as opposed to much higher turnout in even-numbered years. A higher hurdle may be no chance at a teachers union endorsement, even if she had announced her candidacy before the union's PAC board had voted on whom to support: "According to our bylaws, we can't interview candidates who haven't filed," says Elizabeth Thiel, president of the Portland Association of Teachers.

Cale is a Facebook admin for both the main St. Johns and the N/NE PPS Enrollment Balancing groups, on which a lot of the candidate recruitment played out. Greene says he joined the N/NE group on March 30, and “had been made aware that there was questions on that page about my support for the LGBTQ community,” which he says he addressed in a March 30 Facebook Live video he called “Straight Talk: Episode 1: Open or Closed,” stating his love and respect for all. He acknowledged to Portland Monthly that “some of the hurt people have felt and experienced in the past has come from the church.” (He hints that some of the criticism may be about other churches, as well. There are many churches called Abundant Life, including another on the same street.)

“We have spoken, Herman and I,” Cale says of the only other candidate of color in the race, “and we both agreed we are good choices for the city.”

“I thought it was a great conversation, personally,” says Greene. “I needed her to know from me that this would not be a campaign that had any slanderous ... we’re not going to vilify anyone, anything along those lines.” Indeed, the two seem to have a pact to not speak ill of the other.

With Cale and Greene running in Zone 4 and another Black candidate, Gary Hollands, running for the open seat in Zone 5 (mostly Northeast Portland east of 21st Avenue), the next board could have three Black members for the first time. Also on the ballot this year is the seat for Zone 6 (roughly east of César E. Chávez between I-84 and Holgate, with a bit of outer Northeast, too), for which Julia Brim Edwards is seeking a third term and has attracted two challengers. All the Zone 6 candidates are white.

Such representation on the board “could usher in a new era for the district and how it serves children, especially children of color,” says Moore.

DePass is less sanguine. “I feel like the connection between serving on the board and that translating into success for Black children—the straight line isn’t there,” she says. “It’s really, really hard to make change.”

"At the end of the day, no matter what zone, white or Black, what it comes down to is taking care of the kids," Correa said last week, adding that she's had to mute Facebook notifications after her brief but stressful candidacy. "The ultimate ending of this? I wish I had never gotten involved."