Why Are We Surprised by the Women's Soccer Allegations?

Mana Shim in her time with the Portland Thorns.

If you’re even a casual Thorns fan, you’ve likely heard by now that former coach Paul Riley is alleged to have sexually coerced multiple players both while he worked in Portland and before he was hired by the club. The Athletic published a piece on September 30 in which Mana Shim and Sinead Farrelly, two beloved Thorns players from the early years of the team, revealed detailed allegations of sexual coercion. Onetime Thorns player and World Cup star Alex Morgan, who says Shim and Farrelly confided in her at the time and who helped Farrelly push the league for action earlier this year, also went on the record. (Riley has denied the allegations.)

Stacked on top is the revelation that the Thorns fired Riley following an internal investigation of those allegations but did not reveal that publicly—neither when they announced his dismissal nor when he was later hired by the Western New York Flash. They did, apparently, inform the National Women's Soccer League office. Those who were informed also, it seems, did nothing.

The allegations from Farrelly and Shim reflect the most horrifying abuse of power to come to light in American women’s soccer in recent memory. What makes it feel so much worse is that it comes on the heels of a parade of other such cases. Including Riley, who has been fired by the North Carolina Courage, five NWSL head coaches and one general manager have been dismissed this season for various forms of abuse and sexual misconduct. The sheer volume feels catastrophic. The league can’t continue like this.

None of this is new. We’re only hearing about it now because players are starting to demand better. We, the fans, want the Thorns to be a retreat; a place of joy and safety we can turn to when the “real world” feels dark and dangerous. We want to believe the world of women’s sports is better somehow—less rife with casual misogyny, racism, and homophobia, less violently patriarchal, less indifferent to general human suffering—than the men’s.

But sports are not fundamentally good or bad. They exist exactly where society at large does. How, then, did we ever think a league for women and nonbinary athletes who are grossly underpaid and whose teams are primarily owned and managed and coached by rich cis white men, could possibly be a safe space for those athletes?

A few years ago, I believed most men involved in women’s sports respected women. But it’s not true; this space doesn't attract people who are fundamentally different from disgraced former Clippers owner Donald Sterling or New England Patriots owner Robert Kraft. Because they are a cheaper investment—because women athletes are paid less, because they are valued less—women’s leagues may simply attract men who are marginally less rich.

So you never built your own business empire, or you can’t afford to buy a “real” sports team, or you never made it as a professional player yourself? If you have a mid-shelf coaching license or a couple million bucks, likely somebody will hand you control over a group of women, in the form of an NWSL team. And watching this story unravel through the trauma of the players at its heart has shown the damage that kind of control—and the desire for it, whether over another person’s body or as the “good guy” whose desire to protect is another kind of control, depriving women of their own subjectivity—can do.

Some, like Bill Predmore of the Seattle/Tacoma-based OL Reign, will hire a coach like Farid Benstiti, already alleged to have verbally abused a player, then keep him on an extra tight leash. When that coach later repeats the exact pattern of abuse that was widely reported on at the time of his hiring—as when Benstiti allegedly body-shamed Reign players in front of the team—well, what more could Predmore have done, from his perspective?

In the case of Thorns owner Merritt Paulson, who knew what Shim and Farrelly had accused Riley of and still sent him on his way with a friendly handshake, I wonder if this element of control means his concern with safety ends with his own team. Was Riley no longer a concern once he didn’t pose a threat to Paulson’s players? (On October 4, Paulson published an open letter to Thorns fans, saying "we could have done more.")

“From early on,” Shim said this morning on the Today Show, “there was a possession, not just from Paul but from the team.”

To be clear, the structure of control is not only upheld by men. Both the league commissioner and its general counsel at the time Farrelly brought their complaints to the NWSL were women. At least one woman, former GM Alyse LaHue of New Jersey/New York–based Gotham FC, has been fired for abuses of power. All of them have kept that structure intact.

I don’t want to tie this up with a neat little bow. There’s no “answer” to this problem, no one person the Thorns or the NWSL can fire to make this go away. Events are still in motion, and for my part, I am still discovering, hour by hour, new layers within the story to be disgusted by. I have only gotten angrier as I’ve sat with this since Thursday morning. I can’t imagine what Shim and Farrelly and all the god-knows-how-many other victims of abuse in this league are feeling, or any of the fans for whom this is triggering memories of their own trauma.

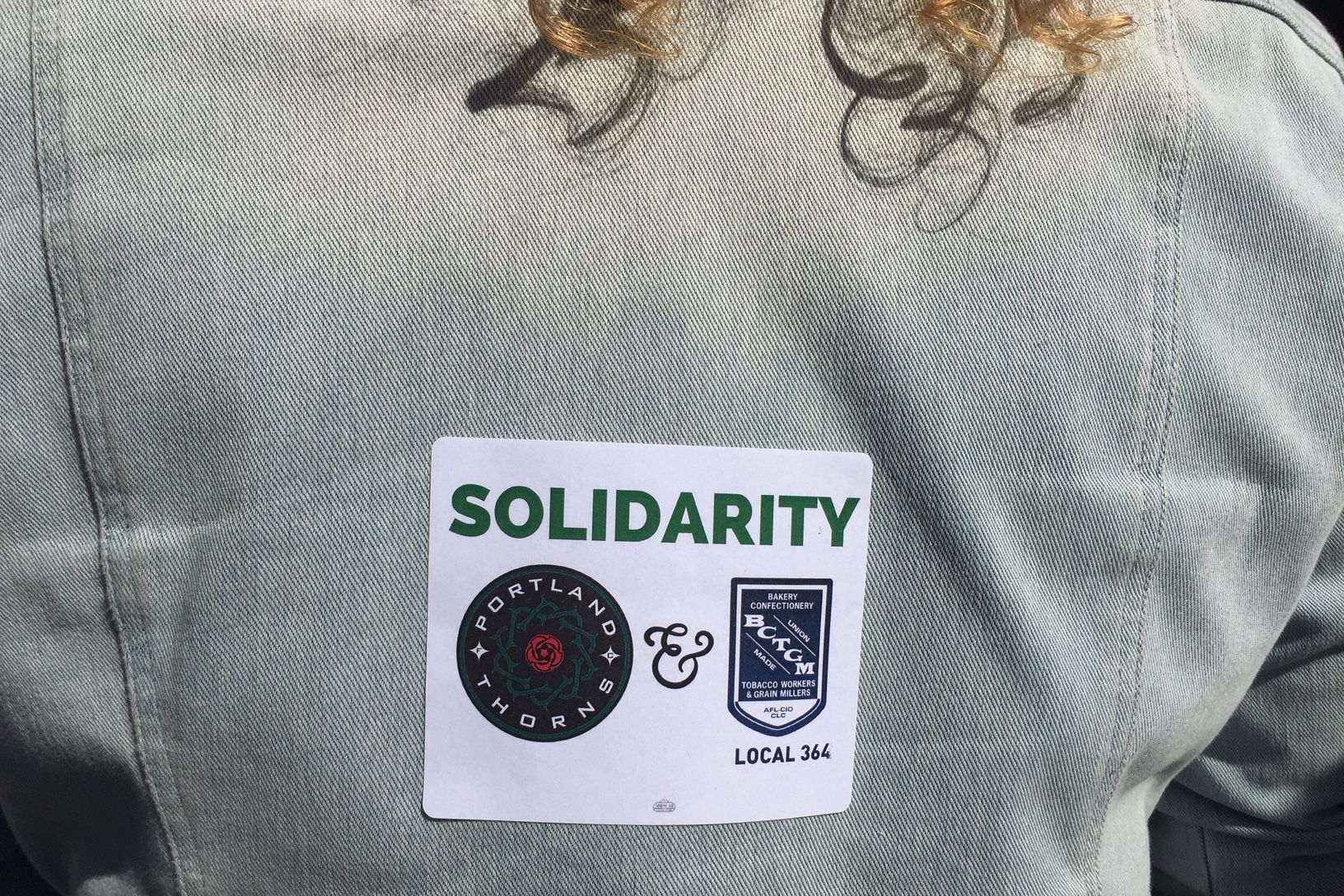

What I do want to say is that because this is about power, the only thing that blows the structure up is the players taking power into their own hands. They have a union that’s been recognized by the league since 2018. They’re currently embroiled in collective bargaining talks. A few weeks ago, a handful of Thorns players walked the picket line with striking Nabisco workers, as if to say, “See? We could do this, too.” We, as fans of the beautiful game, are behind them.