Portland Soccer at a Crossroads for Timbers and Thorns Fans

Image: Michael Novak

Portland soccer fans are tired and wounded. For almost two years they’ve dealt with a string of scandals that have made the teams they love a focal point of national headlines detailing everything that is wrong about the sport in the United States, including credible allegations of sexual misconduct, domestic violence, and cover-ups. It’s been a tough road for anyone who calls themselves a supporter of the Portland Timbers/Thorns Football Club (PTFC), the joint men’s and women’s organization long held up as a model for pro soccer in the US. Many of those fans don’t see that rough ride coming to an end soon—nor do they want it to.

It’s not that they don’t want to see the teams prosper under new management (and, imminent for the Thorns, new ownership), but rather, they know that real, transformative change isn’t something that happens overnight.

"It’s been a really trying two years,” says Gabby Rosas, board member with the 107ist Independent Supporters Trust, the nonprofit organization that coordinates both the Rose City Riveters and Timbers Army, fan groups of the women’s and men’s teams, respectively.

"I think before that I was kind of living in a bubble of ‘Yay, everything is awesome, everything is better in Portland,’” she says, noting that women’s teams don’t always have the institutional and fan support the Thorns enjoy. The Portland team, which won their third NWSL championship in a decade in 2022, draws one of the largest crowds in the world for women’s sports: the year before the pandemic, an average of 20,000 fans packed Providence Park for each home game.

"When the Athletic article came out in September 2021, that bubble burst,” Rosas says, referring to national soccer journalist Meg Linehan’s detailing of alleged sexual coercion on the part of a former Thorns coach, and the decisions by PTFC management that enabled him to keep working in the National Women’s Soccer League. Owner Merritt Paulson and execs faced pressure—including demonstrations in and outside the stadium and season-ticket cancellations—to have their mea culpa moment and get the club in order so the team, its fans, and the city can move forward knowing things would change.

That didn’t exactly happen.

Instead, a few months later, a separate scandal took over the headlines for the Timbers, the once minor-league team Paulson bought in 2007 and which joined Major League Soccer in 2011. This time, there were questions about the club's handling of allegations of domestic violence against a player, which the organization had known about since May 2021. MLS eventually fined the team $25,000 for failing to follow league reporting rules, and the team reached a settlement with the player’s ex-partner in a federal lawsuit.

“That was evidence of ‘OK, there is actually something going on systemically,’” not just on the women’s side, says Kyle Jones, a longtime PTFC fan and member of the 107ist who didn’t renew his tickets for 2023 season, which starts February 27 for the Timbers and March 26 for the Thorns.

Last summer, an Oregonian article depicted a “toxic” work environment, as described by former PTFC employees. In fall 2022, the reports of an investigation led by former US Deputy Attorney General Sally Yates and a DC-based law firm and another by the NWSL Players Association, both initiated after the Athletic article, dog-piled on the bad news, airing more details of just how deeply the rot spread within PTFC and across the women’s pro league. In October, Paulson announced the firing of Gavin Wilkinson—who had already been removed as general manager of the Thorns but still held that title for the Timbers—and president of business Mike Golub.

Paulson also announced he would step down as chief executive of both the Timbers and Thorns clubs, and he later announced he would sell the Thorns, the women’s team Paulson’s Peregrine Sports has owned since its inception in 2012. (The NWSL started play the following year.) Many fans believe he should relinquish ownership of both teams.

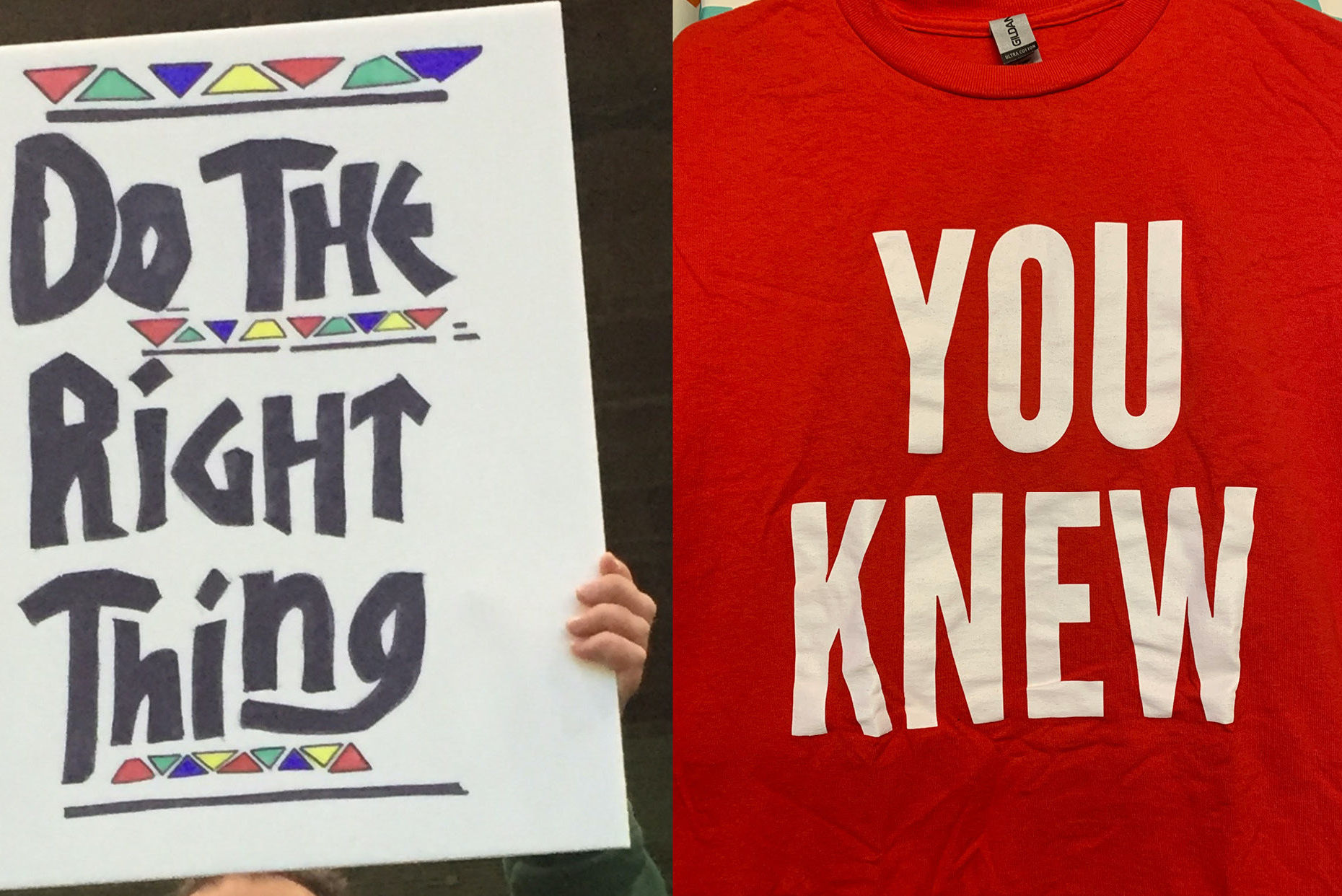

“When you do wrong, there are consequences. You don’t get to be halfsies in and halfsies out,” says Madison Shanley, who sang the national anthem at the stadium for 12 years, starting back when it was still called PGE Park and the Timbers shared the venue with minor league baseball's Portland Beavers.

View this post on Instagram

She parted ways with the team last spring, following a protest she made by singing the anthem while wearing a shirt emblazoned with the words “You knew,” a reference to the front office’s lack of disclosure of both the sexual misconduct allegations against the former Thorns coach and the domestic violence allegations against the Timbers player. She doesn’t want to see the two teams split but wants the offenders out. Those who were “toxic to the community just need to be removed,” she says. “I don’t think they should have any say or ownership or direction in what happens to these teams.”

A lot of fans agree, saying there can be no reconciliation without total change in ownership.

“If [Paulson’s] not good for one team, he’s not good for the other,” says Chris Bright, one of the leaders of the group Onward Rose City, a fan-led effort to purchase the club to keep it intact. Bright and his partners envision a future for the club where supporters oversee what decisions take place in the front office at a 10,000-foot level to ensure their values—social justice, inclusivity, and a safe environment for the players being chief among them—are upheld.

"You want to love the team and love the experience, but there's this whole shadow where there's a culture or institution that is hurting people or protecting people who are not living up the values of what I want as a human being,” Bright says.

Fan ownership is not a new concept by any measure. It’s common in European soccer for association teams to be partially fan owned. In US sports, the most famous example is the Green Bay Packers, which has been owned by a nonprofit, community-based corporation since the 1920s.

Bright believes it’s the only way forward for PTFC if the organization is to live up to the standards of its heart and soul—their supporters.

“There are bigger problems to solve in the world, for sure. But I also feel like these teams are important to people,” Bright says. “They’ve saved people’s lives. They give them somewhere they can finally belong. That’s powerful stuff.”

While fan ownership feels like a long shot, it’s an attractive option for many.

"I love the idea of it,” Jones says. “I would totally be supportive of fans having a stake in the club. I just don’t think it should be entirely fan run, at least not in the short term.” Jones cites reliance on people volunteering their time to help the organization run and a lack of expertise in professional sports as his two main concerns about majority fan ownership.

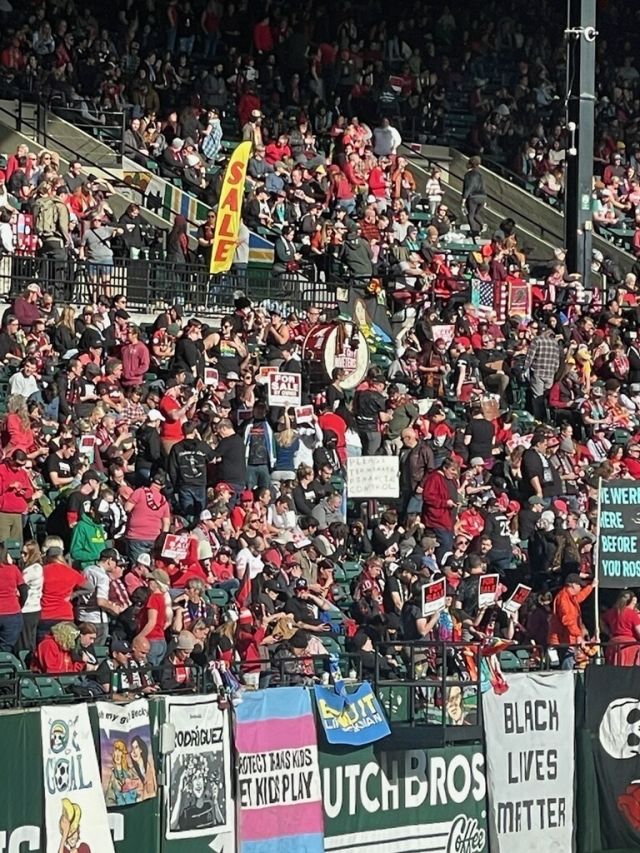

PTFC fans hold up "For Sale" signs during a Thorns match last season.

Image: Ramona DeNies

According to media reports, the two teams combined are valued at a whopping $685 million, of which the Thorns represent around $60 million of that. (Technically the Timbers are owned by Major League Soccer, and local owners are shareholders in the league, which would mean a slightly more complicated transaction than selling the Thorns.)

Whether an investment group of supporters could come up with that kind of cash to purchase the Thorns is a huge question no one seems to want to take a shot at answering. Other possibilities that have emerged in the months following Paulson’s announcement to sell the Thorns include a women-led investor group headed by former Nike executive Melanie Strong. Strong’s group did not respond to a request for comment for this story.

On Twitter, fans have been buzzing with excitement over pie-in-the-sky names like Ryan Reynolds, whose new docuseries on FX, Welcome to Wrexham, chronicles his and fellow actor Rob McElhenney’s purchase of the 159-year-old Welsh football club Wrexham AFC. It’s not completely out of the realm of possibility for Reynolds to consider purchasing one or both teams with his connection to Portland as part owner of the Aviation Gin brand.

"It would be really cool to have [Reynolds] own the team,” Shanley says.

Celebrity ownership already exists in the NWSL. Angel City FC, the Los Angeles team that debuted last season, has more than two-dozen celebrities and influential athletes—a majority of them women, including American soccer god Mia Hamm, pop star Christina Aguilera, and actors Uzo Aduba, Jessica Chastain, and Gabrielle Union—as part of the ownership group.

"We want this to be somebody who is there first and foremost because they are fans,” Jones says. “They want to see the team successful, they’re not just there to get a paycheck.”

At least one local celebrity's name has surfaced in conversations about potential Thorns buyers: Nike cofounder Phil Knight, who has made huge donations in recent years to candidates who may have platforms not supported by many PTFC supporters.

Rosas says it’s an interesting prospect because, in terms of the larger picture that is American soccer, Paulson is “probably one of the more progressive owners within the MLS.”

"That doesn’t mean we need to overlook what [Paulson’s] issues have been and say, ‘Well, he should stay because he’s serving that role [as a progressive owner],’” Rosas says. “That’s not accurate. That’s not justice.”

Rosas says she’s had many conversations with friends and fellow organizers of the 107ist about what ownership would look like under a person—or corporation—whose values don’t align with the club’s supporters. It’s an uncomfortable truth that fans might have to navigate as the Thorns sale pushes forward.

But, Rosas says, “That shouldn’t stop us from pushing for change and pushing for accountability.”