He's Thought about This Death of a Houseless Man Since 1987

Image: katherine lam

I first saw him in April 1987. It was springtime. The world was growing greener, and he was pushing a shopping cart rattling with white Meister Bräu beer cans, some of them empty, some of them full. He had several missing teeth.

His name, I would learn, was Jerry Wayne Jacobs. He was 37 years old, 5-foot-8, 170 pounds, and right away he laid claim to the vacant lot next to the dilapidated Craftsman I was renting with friends on NW 24th Place, a dead-end street. Jerry said he was a paleontologist, and he was there to dig fossils out of the ground. If anyone disbelieved this claim or rolled their eyes at its absurdity, Jerry raged. He became red in the face and began hurling empties.

Jerry was not well, that was clear, and he was angry in part because he had nowhere to go. He lived on the streets. He eked by on a disability payment, a $900 monthly check he deposited into his account at Ray’s Grocery, in Old Town, where he bought his Meister Bräu and his cigarettes. And I suspect he was lonely. In a police report, his friend Tom Stephens said, “He never made any real sense when he talked.”

There was a weathered, six-unit brick apartment building on the other side of the vacant lot, and when Jerry encountered its residents, he taunted them. He pulled up the plants in the communal vegetable garden on the property. He urinated and defecated outdoors, and the children living in the complex said they often felt unsafe. “I remember a lot of drinking and yelling,” says Kether Bryant-Stanek, 8 at the time. “He was more than a nuisance. He was really a disruption to our lives."

If you live in Portland today, perhaps you have a neighbor like Jerry. The city is now plagued by a homelessness crisis deeper than it has ever experienced. Some 6,000 unhoused people live in the city.

But the city has glimpsed this darkness before—in 1987, the year I met Jerry. Back then, Portland found itself playing host to an unprecedented crisis of homelessness. There were an estimated 6,000 unhoused people living in Oregon. President Ronald Reagan was the main reason. Elected in 1980, Reagan rode into office determined to cut taxes, even if it caused hardship for our most vulnerable neighbors. Budgets for Social Security, Medicaid, food stamps, and public housing plummeted under his watch, and he reduced funding for psychiatric hospitals severely. In 1981, just months into his presidency, Life magazine ran a story titled “Emptying the Madhouse: The Mentally Ill Have Become Our Cities’ Lost Souls.”

The visibility of a homelessness crisis forces a moral question upon us. It did in 1987, and it still does. How do we balance caring and concern with the desire to live in a pleasant environment?

Answering that question has never been more urgent. The murder of unhoused people has been rising nationwide since 2010, and one University of Washington study found that they were 19 times more vulnerable to homicide than the general population.

But even in 1987, the killing of people experiencing homelessness was so common that the Portland Police had a special name for them. “We called them ‘bumicides,’” says C. W. Jensen, a homicide detective back then and later a commentator on World’s Wildest Police Videos, “and they were the hardest to solve because the victims didn’t have roots. They didn’t have neighbors. You could never find their family, and when you put them in an autopsy, they didn’t have any ID on them.”

As April turned to May, Jerry kept coming around with his shopping cart. He seemed to be more or less living in the lot, so enchanted by the place that he invited guests. “One night,” Tom Stephens told the police in 1987, “he kept insisting over and over—let’s go sleep over there.”

To Jerry’s family, it was unfathomable that he’d arrived at such a desperate place in his life. “Growing up, he was popular,” says his sister, Lola Jurca, recalling their childhood in tiny Mount Vernon, Oregon, where their dad was a logger. “He was handsome. All I remember is that the girls loved him. They all wanted to be my friend so they could get closer to Jerry.” He baled hay, boxed in local gymnasiums. And, sometimes, with friends, he dug for bones at what is today the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument. At Mount Vernon High School, he was a reporter for the newspaper, a wide receiver on the football team, and a starting guard on the basketball team. Senior year, he was named “Best All Around.”

But soon after Jerry graduated and began working at a sawmill, he missed a turn while driving outside of Mount Vernon. His ’55 Chevy Bel Air collided with a bridge abutment. He suffered a concussion, and the bones in one of his legs were shattered. As he recovered, says his sister, “The doctors gave him too much morphine. He became addicted, and he was never the same.”

Lyle Williams, who played basketball with Jerry at Mount Vernon, remembers his friend coming back to town in the ’70s and “hanging out in the taverns and sleeping under bridges. Then it just spiraled downhill from there.”

Jerry lingered on our street hoping, I suspect, for a chance to connect with the pulse of the city. And he’d picked a good spot. The apartment building there offered a foretaste of the weird, happening Portland that was to come. The 20-something residents didn’t punch the clock. They were artists. They made zines. They worked at thrift stores, and all their units opened out onto a generous shared porch that encouraged stoop-sitting and the idle exchange of outré ideas.

I, too, haunted those apartments, with an insistence that verged on awkward. I went over there, afternoons, and knocked randomly on neighbors’ doors, hoping someone might come out and chat, for I was lonely and lost myself, in a mild, middle-class way. I’d graduated from college in 1986, then spent eight months malingering around my parents’ house in Connecticut before deciding, in January 1987, to fly west and launch myself as a freelance writer in Portland.

The night we got the keys to our 24th Place Craftsman, I slept on the bare floor, in the cold. The heat was off. Up until then, I’d only slept in my parents’ house or in dormitories. I was hungry for the bruise and hurt of living on my own terms—and also uncertain as to how to turn myself into a viable adult.

Eventually, I made friends with one apartment dweller whom I considered the soul of cool. Mark Burke, 23, was a chef at Crackerjacks, a now-closed bar that today is a boarded-up building on NW Thurman Street. A slight, tattooed seeker with curly hair and John Lennon glasses, he lived with his girlfriend and their infant daughter. He was at ease discussing both Bukowski and Shakespeare. We played hacky sack in the vacant lot, chatting. He seemed to savor showing me how familiar he was with life’s dark side. He spoke of heroin users he’d hung with and of his alleged friendship with Tony Alva, the reigning badass of professional skateboarding. I wanted to know what he knew.

But back home my father was a tax attorney at a white-shoe law firm. My mother, a historian, was painstakingly writing the story of the Underground Railroad. As much as I wanted to escape the primness of my East Coast past, I couldn’t just flip a switch inside myself and become one with Mark’s soliloquies. He and I held different worldviews, especially when it came to Jerry Wayne Jacobs. So, ineptly, I began calling around, hoping to find help for Jerry.

Mark, in turn, ran Jerry off the block. In a 1987 interview with police, he admitted to chasing him away “dozens of times.” He had a method. Wielding a pair of nunchucks high over his head, he lunged toward Jerry, hissing commands like, “Get out of here! Leave!” There was a wiry force to Mark’s attacks, but his gestures were slightly stiff, as if he were surprising himself with his sudden shift from rebel raconteur to bouncer, and I had to wonder why it was that Mark, who stood 5’8” and weighed 145 pounds, had appointed himself our block’s enforcer.

In the confrontations I witnessed, Jerry was passive. “Please,” he said to Mark, “just leave me alone.” He slinked away each time Mark went after him. But he always came back, sometimes within minutes, and I worried that things would escalate. “Why don’t you just call the cops?” I asked Mark.

Mark told me that he had called the police several times. “And that accomplished nothing,” he said.

Eventually, in May, I called the police myself, to report Mark’s violence. They did not come by to investigate. Like Portlanders today who find themselves enduring all-night noise and strangers sleeping in bushes outside their homes, all of us on that block felt like we were living outside the bounds of civil society, in a world where the rule of law no longer pertained.

Image: katherine lam

Around Memorial Day, I had my own brief interaction with Jerry when I was out on my lawn with a friend. My worn T-shirt sat on the grass, and Jerry picked it up and tried to sell it to my friend as I stood three feet away. We laughed at him. Immediately, he lay the shirt back on the grass and stalked away, seeming hurt.

I felt guilty. Mostly, though, Jerry was on the periphery of my consciousness until June 7, 1987, the last day of his life.

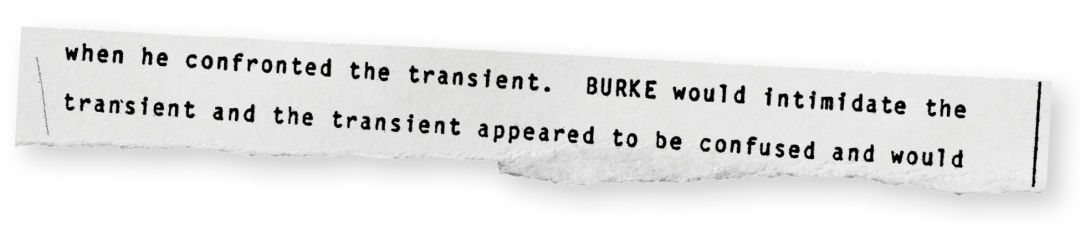

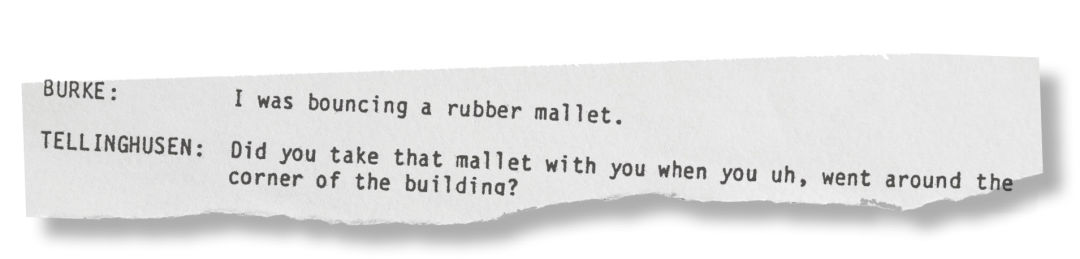

Mark got off his shift at Crackerjacks at 9:30 that evening, according to an interview he later gave police. He walked five blocks home through the fading light and met a couple of other apartment dwellers on the porch to build a swinging bench. When Jerry showed up in the garden at around 9:45, Mark happened to have a rubber mallet in his hand. He carried it out to the garden—“unconsciously,” he’d tell police—but now, for the first time ever, Jerry fought back. “He swung around with a, I think an open fist,” Mark said in his interview with the cops, “and caught me upside the cheek and the neck area, latched onto my shirt and dragged me to the ground.... At this point, I was in the midst of a fight ... a fight for survival.”

It wasn’t clear who would win. Mark had the mallet, but Jerry had boxing experience, and he outweighed Mark by 25 pounds. Mark was “more afraid than I had ever been in dealing with him,” he told the police. “We were about to hurt each other.”

As it turned out, a friend of Mark’s was watching, with hysterical concern. Ronald “Dino” Lange, a 41-year-old Vietnam vet, had recently met Mark on the street and become a Crackerjacks regular. The night of the confrontation, Dino followed Mark home from the bar—on his own initiative, it appears, without Mark’s invitation. He was a hulking biker who’d been discharged from the marines years before because he was afraid of violent conflict. To me, he seemed pathetic—almost sycophantic—around Mark. I’d seen him outside the apartment building, a bearded, Viking-like giant lumbering amid waifish indie rock types in his shiny black leather vest. Later, in court papers, a lawyer would argue that he carried a “passive dependent” regard for his young friend.

On the afternoon of June 7, Dino had consumed three pitchers of beer at a motorcycle swap meet. And when he arrived on our street, he decided that Mark was in extreme danger. He grabbed the mallet out of Mark’s hand “mid-swing,” Mark said, and hit Jerry “in the shoulder, side of the head, and the back of the head. Sort of knocked him progressively down to his knees.”

From the apartment building, according to Mark, someone shouted, “Hurt him good, but make sure he can walk.”

Dino didn’t speak. He was in such a rage that, even five hours later, during an interview with the police, he couldn’t explain why he’d decided to engage in the attack. He told the cops, “Something inside of me just said, ‘Whoa, wait a minute. This isn’t right.’”

Now, Dino just kept hitting. Jerry went limp, eventually, bloody and unspeaking. He just rolled his head with each of Dino’s blows. As Mark watched, a part of him felt gratified. “I don’t blame [Dino] for not valuing JWJ’s life,” he’d write years later. “He saved mine, the life I value.”

Eventually, Mark hoisted Jerry into his shopping cart and then rushed him down the block, past my house, and left him, crumpled and breathing raggedly, in a bar parking lot. Jerry died there moments later.

In a legal memo prepared in advance of Dino’s trial for murder, Dino’s lawyer, John Clinton Geil, would argue that the preponderance of blame lay with Mark Burke. “This tragic incident,” he wrote, “would never have happened had it not been for Burke’s previous confrontations with the decedent which escalated into the fight which Burke started.”

In talking to police, Mark equivocated as he considered his role in the killing. He said, “I’ve a lot of guilt and remorse for my participation in this brutal beating of this man,” but he also said, “I feel that my actions were justified.” He added, “I could not account for the transient’s actions or Dino’s actions.” After the moment he claimed to have told Jerry to leave on that horrible night, he said, things “took a haphazard course” and “it tumbled out of control.”

I was at the movies that night, and when I arrived home around 10:30, there was yellow police tape everywhere on the block. I climbed the front steps of our house and went inside. The lights of a police cruiser were flashing red and blue on the walls of the living room. I couldn’t sleep, and sometime in the early morning, I called the Portland Police and said, “I know who did it.”

Actually, I didn’t know who did it. I wasn’t aware of Dino’s involvement. But I knew Mark had a role in the buildup, and on June 10 a cool, muscled cop and his partner transported me to the Central Precinct and interviewed me. “DONAHUE worried that BURKE would do severe physical harm to the transient,” read the police report that ensued. “DONAHUE called 911 to have the police intercede.”

Over the summer and into the fall, as prosecutors readied their case, I kept asking questions on reporting missions about what levels of civility and decency we owe the unhoused. I was becoming familiar with the fear and hatred that people can harbor for other humans in crisis. I’d seen firsthand how disposable people living on the margins can be. So when I was called to testify before the grand jury on the killing of Jerry Wayne Jacobs, I had no illusions that Mark and Dino would be seriously punished for what the police labeled “bumicide.”

Both perpetrators waived their right to be tried by a jury for murder; both pled guilty to manslaughter. Dino got seven years and served less than three. Mark got one year. With credit received for time served pretrial and a two-month early release, Mark was back in the neighborhood in 1988.

A few days after his release, Mark came over to my house and knocked on the door. His manner was surreally civil—contemplative and cerebral, even. I wasn’t afraid for my safety. I’d never considered Mark an exceptionally violent man. He was, rather, a complex character who’d been spurred into violence by structural problems that still plague us.

I let him into my house and we sat down at the kitchen table. “I spent 10 months of my life in jail because of you,” he said. No, I told him, he had spent 10 months of his life in jail because he was complicit in killing someone.

“I heard the tape of you calling 911,” Mark replied. “You seemed scared, Bill.” Mark was right. I was scared when I called 911, and I was scared sitting there in the kitchen, discovering that Mark knew what was at my core. For I was made of fear in those years. I was scared, to be honest, from the moment I got on the plane and flew west. I was a gangly kid trying on adulthood for size.

Over the past 36 years, I’ve tried many times to write about that killing, but my fear has kept crushing down on me. It just seemed too big, too horrific, to assimilate, even after Dino Lange died in 2011. And I knew that, if my account of it was to work as journalism, I’d need to contact Mark and give him a chance to comment, and I just couldn’t bring myself to do that.

Finally, though, this past spring, I wrote to Mark. He’s 60 now. Retired, he lives off-grid in Hawaii, his knees and hips worn ragged after a career as a Bering Sea fisherman. He still sees his attacks on Jerry as reasonable. “JWJ lived like an animal,” he wrote. He was “unfit to live in free society.” Mark did feel that, for his role in the killing, he bore a guilt that was “emotionally taxing. My Catholic/societal burden of responsibility demanded punishment.”

Eventually, Mark told me that he “almost got violent” with me when I called the cops after the killing. But he added that his contempt toward me was a passing fever. “I ... didn’t begrudge you,” he said. He “would have done the same thing,” passing along the information and letting the authorities sort it out. “Cause in the end the system actually worked.”

The system worked? I will never agree with Mark. For now, finally, I can see the spring of 1987 clearly. When danger rose, I moved past my fear. I stood up. I tried to stop the violence, but I did not do enough. Amid the push to sanitize our street, I watched humanity leech away. Things tumbled out of control. And a man died and the police lights flashed on the walls of my living room, and for a long time on NW 24th Place, the block was pleasant for no one.