Year of the Nurse: The Friendly Smile

As the battle against Covid-19 rages on, it’s vital to recognize the brave men and women who, every single day, risk their health to protect ours. That’s why Regence BlueCross BlueShield of Oregon is dedicating this special series of articles to eight local and regional nurses who, through their compassion and humanity, have made the difference for thousands of lives.

For more than 20 years, John Rodriguez forged his medical background in the fields, forests, and snowy slopes of southern Oregon, where he was born and raised. As a ski patroller, he made a living as a wilderness EMT, but he wanted to contribute even more to society. “My joke is: you’re out in the woods for three days, so you can only treat a three-day injury,” he says. “I kind of wanted to go beyond that.”

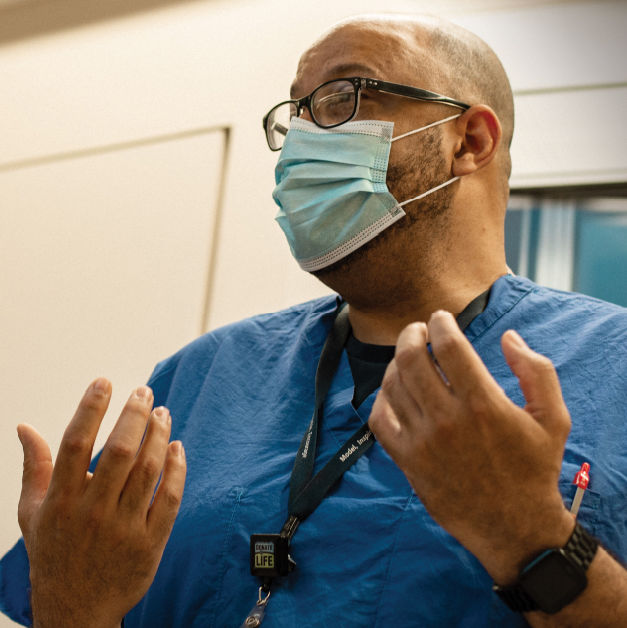

John Rodriguez at Asante Rogue Regional Medical Center

Image: Ben McBee

His backcountry training made him adept at soothing people in traumatic situations, so it’s not altogether surprising that his next step was to become a nurse at Asante Rogue Regional Medical Center’s emergency department in Medford. The hospital services the surrounding nine counties; if you’ve had a heart attack, suffered a stroke, or broken something, you go there.

“In my eyes, everybody has it until it’s proven they don’t,” says Rodriguez about Covid-19. On top of the mental strain that vigilance causes, the full-body protective equipment is a heavy physical burden, too. “Imagine your glasses fogging up, behind a face shield and mask, when you need to start an IV on a 3-year-old kid who is screaming frantically,” he says. “Your heart rate goes up. You’re already sweating. The medicine we do is challenging now.”

Rodriguez no longer wears his own scrubs to work. His street clothes go in an outside bin to get taken to a laundromat, and he showers before joining his family. “There were probably six weeks when I didn’t come into my kitchen or living room,” he explains. “When I didn’t share the same bed as my wife, when I couldn’t hug my children.”

His youngest daughter, Maleah, recently graduated high school with a socially distanced ceremony, and her plans to play basketball at Eastern Oregon University had to be scrapped. For Rodriguez, his family is his life, and to see their sacrifices breaks his heart. “My job, I work here, but this is just where I earn my keep,” he says. “My place at home, trying to keep my kids positive and out of depression, that’s been the challenge, and I don’t think that is unique to me.”

Wearing a mask, much like wearing a seat belt, shouldn’t be considered anything other than a safety measure to protect public health, but unfortunately in this climate, that’s not the bottom line. “I see people put the mask on so they can go into an establishment, and as soon as they get in, they take the mask off,” he says. “On the one hand, yeah, that makes me mad. I think that’s selfish. Out of the other side of my mouth, I’m going to say: Help each other out. Allow grace right now. Things are different; everybody is more stressed. You hear people sneeze, and you think someone’s fired a weapon. We can’t live in fear our entire lives, because that’s just not living.”

Even though he’s a glass-more-than-half-full kind of guy, Rodriguez knows if people aren’t willing to help mitigate coronavirus, the consequences are going to be severe and long-term—a reality he sees in his patients. He’s witnessed genuine fear in a young, by all appearances healthy, person’s eyes. Someone who didn’t drink, smoke, have asthma, or any underlying conditions, but still became extremely sick.

“That hit me pretty hard,” Rodriguez says. “I sat in their room on two different occasions in full garb. I’ve got the respirator on, the hood on, my eye goggles, the gown that doesn’t breathe at all. I sat there and held this patient’s hand, and I just did my best to encourage them. At the end of the day, maybe I did. They were smiling anyways, versus tears when I walked in the room. I think that’s impactful.”