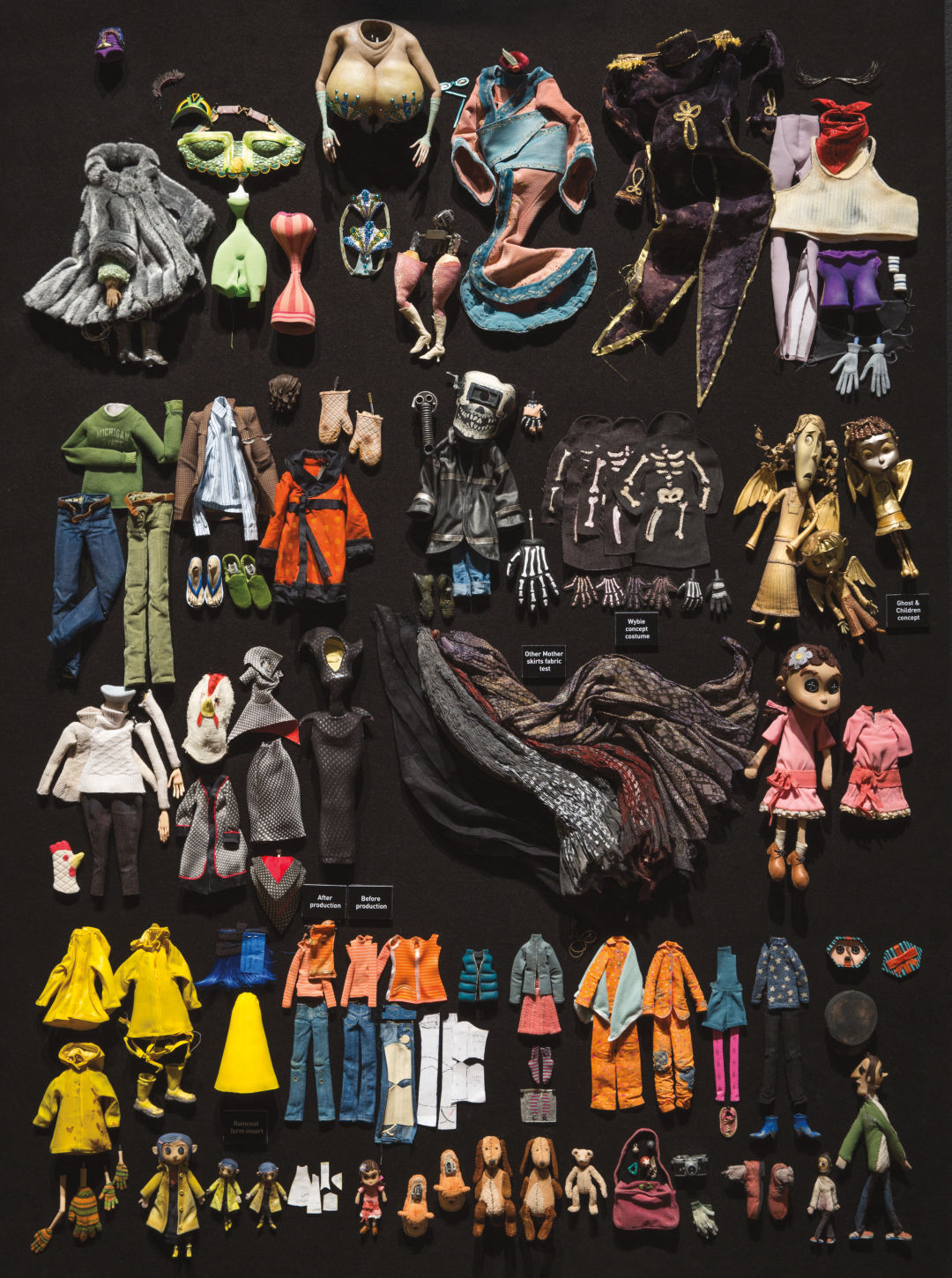

How Laika's Costume Designer Dresses Tiny Puppets for the Big Screen

From fresh and clean to patched and dingy, costumes from Coraline are on display at the Portland Art Museum.

Image: Courtesy Steven Wong/Laika

Laika costume designer Deborah Cook chats about 17-inch-tall puppets the way most people reminisce about old friends. “I love the Sisters. There’s an elegance to them,” she says of the terrifyingly beautiful villains in the Hillsboro stop-motion animation studio’s 2016 hit, Kubo and the Two Strings. “Their faces are a 14th-century Japanese Noh theater mask. To have something that still, against their moving capes, stands out so much. It feeds into them being quite eerie and scary.”

She’s appraising her mini masterpieces while nodding to tiny textured outfits behind glass at the Portland Art Museum’s current Laika exhibit, which runs through May. The entire show is a wonderland marrying creativity and technology. And Cook, who has been with Laika since its inception in 2005, is one of the strongest threads stitching together the studio’s insanely detailed worlds. A looming 18-foot-tall skeleton—the largest stop-motion puppet ever animated—stands feet away from a red 2-inch warrior, the smallest puppet Laika’s made. The elaborate fantasy garden from 2009’s Coraline takes up the center of one room, while ParaNorman’s house, perfect right down to the lid-askew garbage can around the side, commands another corner. Then there are the puppets, including the Sisters—all perfected down to every hair, bespoke microsized button, and thought.

Deborah Cook in her studio and at work with an embroidery hoop

Image: Courtesy Laika

When it comes to costume, research is everything: “We built Kubo and the Sisters with history strongly in mind, using Japanese prints and elements of funeral gowns. The pants are traditional hakama pants, and these hats were female ninja assassin hats,” says Cook. The designer decamped to Tokyo for Kubo, combing through vintage kimono fabrics, visiting samurai museums, and immersing herself in extensive research for the richly imagined looks. “We looked at historical images on how feathers had been drawn, how different birds have mythological meanings. For the Sisters’ capes, each feather is a different shape, and the 400 of them are individually stitched to the winged mechanism.”

The level of detail and research for each character would drive a less dedicated designer mad, but Cook’s been obsessing over minutiae since childhood. Raised in Bristol, England—another cool city with a bursting music scene, a pretty river, and creative people—she started collecting bits of fabric that “spoke to her” in a box. “I never really knew what for, and I still do that today,” she explains of the lifelong habit, which makes her office a precarious pile of fibers, books, and inspirational snippets from fabric stores, contemporary fashion magazines, and articles on breakthroughs in textile science. “They’re really essential even if they don’t become something,” she says. “They bubble away in your brain.”

She headed off to the illustrious Saint Martin’s College in central London to study sculpture, but was also heavily influenced by the fashion, photography, and film students all around her. In the 1990s, the college was a freelance hub for London’s film and TV industry. Cook built up her résumé making figures and installations for small films and local series—building relationships as she went in the small but influential stop-motion animation community. Now, her résumé reads like a stop-motion sizzle reel: Tim Burton’s Corpse Bride, Fantastic Mr. Fox, all the Laika films, including the studio’s two upcoming features. Every released film she’s worked on has received at least one Oscar nomination. Kubo also achieved an industry first last winter: a nomination for Excellence in Fantasy Film from the Costume Designers Guild, unprecedented, in the awards’ 19-year history, for an animated film. (The prize went to Doctor Strange, but it was still a massive feat.)

Clockwise from top left: The Boxtrolls, one of the Sisters from Kubo and the Two Strings; ParaNorman, and Coraline

Image: Courtesy Laika

With three decades in the industry and copious award nods, Cook remains humble. She’s focused on Laika’s ever-soaring quality of work, which she credits to her team (many of whom have worked together for 13 years), studio department growth (Coraline had a costume team of five; Kubo quadrupled that number), and new techniques and technology.

“Each film is leaps and bounds above the one before. We become more self-sufficient. We don’t buy off-the-shelf fabrics anymore,” she says, rattling off all the things her team is now able to do in-house.

They create their own minuscule chains for a wallet detail, use Tyvek under silk to create a worn texture, and digitally program lace. Then there are the explicit methods used to make and track a tea stain on a cuff of a puppet’s sleeve, from the second it’s submersed, and at exactly what angle, for screen continuity across the multiple versions of costumes they make for each character look. It’s a lot.

That combination of creativity, innovation, and excruciating detail is what makes Cook’s work stand out, according to Nelson Lowry, Laika’s supervising production designer. “Her costumes are at the apex of design for our films,” he says. “They make the character more human.”

Big Numbers for Little Wonders

Laika Studios works out of a 151,140-square-foot building in Hillsboro.

Coraline (2009) was the first-ever stop-motion animated feature to be conceived and shot entirely in Stereoscopic 3-D. It took more than 500 people and four years to complete.

Laika shoots 24 to 27 frames per second, with a different pose for each second, with costumes moved slightly for each. On average, each animator shoots only about 3.31 seconds of film per week.

Each puppet shoe has to be handmade to accommodate an armature that moves like a real foot walking.

Cook has used antique Victorian leather gloves to make puppet footwear, as the material is already worn smooth and she knows it’ll last through years of filming.

In ParaNorman, there are 275 spikes in Norman’s signature hairstyle. His do was primarily made from goat hair held together with hot glue, hair gel, fabric, and super glue.

A knitter crafted Coraline’s teeny gloves by hand using miniature needles, some of them as fine as human hair.

In Kubo, Monkey’s fur texture (from the neck down) is completely hand-trimmed. It took one artist several days to give her that intricate haircut.

Purchase orders from Kubo’s production include: 1,300 feet of giant origami paper, 4,392 English beading needles, 79 eight-ounce bottles of white Wilton nonpareils and 243 pairs of Calvin Klein hipster undies.