Discovery Channel

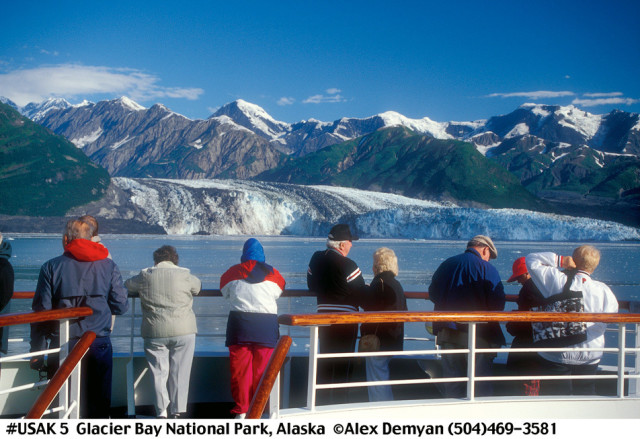

Even when viewed from the fourth-floor deck of a behemoth ocean liner, the berg-clogged bays of Alaska’s Inside Passage will cause your jaw to drop.

Image: Alex Demyan,Alex Demyan

Until late last summer, the closest I’d ever ventured above the 58th parallel, and the nearest I’d come to the Last Frontier, was the John Wilson Room on the mezzanine of Multnomah County Central Library. There, seated at a great oak desk, surrounded by medieval manuscripts and other treasures locked away in glass cases, I’d flip through a weathered gray translation of The Voyage of Discovery , Captain George Vancouver’s account of his search for the fabled Northwest Passage. While surveying the coast of the Pacific Northwest at the close of the 18th century, Vancouver, at the helm of the ship HMS Discovery , charted a narrow, thousand-mile-long waterway that was wedged between ice-clad mountain ranges jutting a mile or more into the sky.

The passage ended at a dam of glacial ice 300 feet tall.

Unfortunately, the channel ended not at the gateway to the Atlantic Ocean, Vancouver’s intended goal, but at a dam of glacial ice 300 feet tall and five miles wide. He had stumbled upon the Inside Passage, one of the most beautiful stretches of water on the planet.

Since then, many explorers have plied the Inside Passage, chief among them the naturalist John Muir, who paddled the route with an Indian guide in the autumn of 1879 and discovered that the ice dam at its terminus had melted away, revealing a fjord ringed by a dozen tidewater glaciers. Upon seeing Glacier Bay for the first time, Muir wrote, “Our burning hearts were ready for any fate, feeling that whatever the future might have in store, the treasures we have gained this glorious morning would enrich our lives forever.”

It was after stumbling across Muir’s exaltations of Glacier Bay one afternoon in the library that I vowed to chart my own Alaskan voyage. If I had my druthers, I’d emulate Muir, provision a canoe and spend my summer paddling out to that distant ice-clogged inlet. But in addition to my own druthers, I now must consider those of my wife, Helen (who shares my loathing of group excursions), and the needs of two young children.

Helen and I first investigated plying the passage via the Alaska Marine Highway System, a fleet of 11 state-run ferries that serves 31 ports between Bellingham, Wash., and Skagway, Alaska, including tiny Tlingit fishing villages with names like Angoon and Hoonah. The $2,112 round-trip fare for a family of four on one of these no-frills vessels amounts to half that of an economy berth on the average luxury liner—but then most passengers sleep in tents duct-taped to the sundeck, hardly kid-friendly accommodations.

So we visited a downtown travel agent who specializes in Inside Passage cruises. She steered us to the Norwegian Star , then the newest ship of Norwegian Cruise Lines’ Alaskan fleet, which came replete with a literal amusement park of amenities: three swimming pools, one with twin corkscrew waterslides; a video arcade; two playrooms; a kiddie buffet stocked with an endless supply of pepperoni pizza and chocolate frosted cupcakes; plus a resident magician who performs in a 1,000-seat Broadway-style amphitheater. The weeklong excursion, calling on the Alaskan ports of Juneau, Skagway and Ketchikan as well as Glacier Bay, would cost $3,911.16 for a family-sized cabin for four (offering a porthole view just above the waterline). Loath as I was to pay such a toll, it seemed the most reasonable way to retrace the voyages of Vancouver and Muir with a kindergartner and a second-grader in tow.

On the morning of our departure, I stood on the terrace of a friend’s apartment in Seattle’s Belltown neighborhood just as the Norwegian Star berthed at the terminal a block away, and I couldn’t help but be awestruck by the vessel’s sheer dimensions. The Star stretched 83 feet longer than the Titanic and towered 175 feet above the pier, where a half-dozen semi trucks offloaded provisions to stock the ship’s 13 restaurants. The giddy anticipation of departure only intensified as we ascended the Star ’s gangway and joined 2,200 other cruisers (tended by a crew of 1,100) at the rails, waving at nobody in particular. Then, at the sound of a horn that was felt as much as heard, the great ship nosed north, toward Alaska.

{page break}

Departing Juneau, a cruise ship plies the Inside Passage’s Gastineau Channel.

Image: Alex Demyan,Alex Demyan

The next morning, as I stood on the ship’s bow munching a just-baked croissant and sipping strong coffee from a gilded porcelain cup, I shrugged off any reservations at being a temporary resident of a floating city. The sea crashed like a roaring waterfall around the prow of the Star , and on both sides of the channel, beaches littered with sun-bleached driftwood delineated a vast coastal rainforest: a cloud-shrouded arboreal sea of western hemlock and spruce stretching east and west in undulating hillocks that would grow into mountains as we headed deeper into Alaska.

Alaska’s capital is a city isolated in the wilderness.

At this hour, the sun’s nascent light cast a pearlescent glow on the water, which seemed as uniform as quicksilver, without so much as a riffle. Then I nearly dropped my cup into the sea, startled by a snort, then a splash that sounded like an air-dropped Volkswagen. Humpbacks! No more than a hundred yards ahead, four—no, six—whales cavorted in our wake, waving barnacle-crusted flukes skyward, then diving for fathoms before hurtling nose-first into the air like submarines rocketing from the deep.

And so the morning passed, as did the next.

At 2 p.m. the following day, the Star arrived in Juneau, where three other cruise ships were already docked at the seawall in Gastineau Channel and another waited offshore at anchor. Alaska’s rain-soaked capital is a city isolated in the wilderness, accessible only by air or by sea, the skyline dominated by boxy concrete-and-steel government office towers, including one the locals call the Spam can. Instead of following the masses out to Mendenhall Glacier or riding the aerial tram halfway up Mount Roberts, we walked to the Alaska State Museum, where our children whizzed right by treasures and artifacts from the state’s Russian past (Alaska was the czar’s property until 1867) and, despite the fact that we had been living on a ship for several days, made a beeline for the quarterdeck of a kid-sized rendition of the HMS Discovery , where they pretended to sail off into the unknown.

At sea two mornings later, 50 miles north of Juneau, an iceberg floated past our porthole, heralding our arrival at the grand finale of the Inside Passage: Glacier Bay.

Helen and I roused our children, cocooned them in wool blankets, took them to the promenade deck and deposited them on lounge chairs with cups of hot cocoa, while we joined the throng at the rails. As the sun rose, the seamless fog that had obscured the bay lifted like a curtain, revealing a sight so magnificent, so—as Muir put it—“indescribably glorious,” I had to hold my eyes open to be sure the image burned permanently into my mind.

While stewards plied the crowd with hot buttered rum from rolling wooden carts, Helen and I held hands and stared out at the face of Muir Glacier, a wall of ice 100 feet tall and a quarter-mile wide, stretching like a frozen superhighway through a valley it had carved for itself. Over the public address system, a National Park Service ranger told the story of Muir’s 1879 sojourn by canoe, how the naturalist was rendered speechless by the “jaw-dropping grandeur” of the vista before us. Bergs drifted by, crackling and popping as they bobbed like styrofoam in the saltwater (as glacier ice melts, it sizzles, releasing air trapped for centuries; on some cruise ships, the ice is netted and becomes the secret ingredient in fizzy Glacier Bay cocktails). The thunder of calving bergs, the “wild aural splendor” of it all, was precisely as Muir had described.

But even his words somehow failed to capture the absolute majesty of the place. As did my camera. To understand what I mean, you’ll just have to go see it for yourself.