River Wild

Image: Matt Baker

The Little White Salmon River guards its glories. A glimpse from a bridge in the hills above the Columbia’s northern bank, 20 miles from Hood River, barely hints at the spring flowers in bloom deep in the narrow canyon, Spirit Falls’ silky 33-foot cascades, or the river’s Listerine-blue foam.

To really see the Little White, you must pilot a kayak through a mad ballet of white water, around boulders packed tight like schools of surfacing humpback whales. Almost hidden in a twisting canyon, the river shoots kayakers down five miles of uninterrupted Class V rapids, too difficult for all but the most expert paddlers.

“The Little White is a gem,” says Sam Drevo, one of Portland’s renowned kayaking veterans. “Undammed, pristine water, fed by springs—a small river that’s quite steep.”

Considered unrunnable before the early 1990s, in recent years the Little White has seen an influx of kayakers emboldened by technological advances: polyethylene boats, buoyancy aids, Gore-Tex drysuits. Each rapid now bears its own name—and Internet-based lore. From all over the world, elite kayakers trek here. Two have died here.

For the small subculture of Class V–capable kayakers in Portland, Hood River, and the tiny town of White Salmon (population 2,200; per capita concentration of pro paddlers, off the charts), being good enough for the Little White is like knowing the password to a secret society. Online, the best simply ask: “Going to church?”

"Kayaking is one of the most lethal sports. When it goes bad, it goes bad quick." - Kayaker Lane Jacobs

Image: Stuart Mullenberg

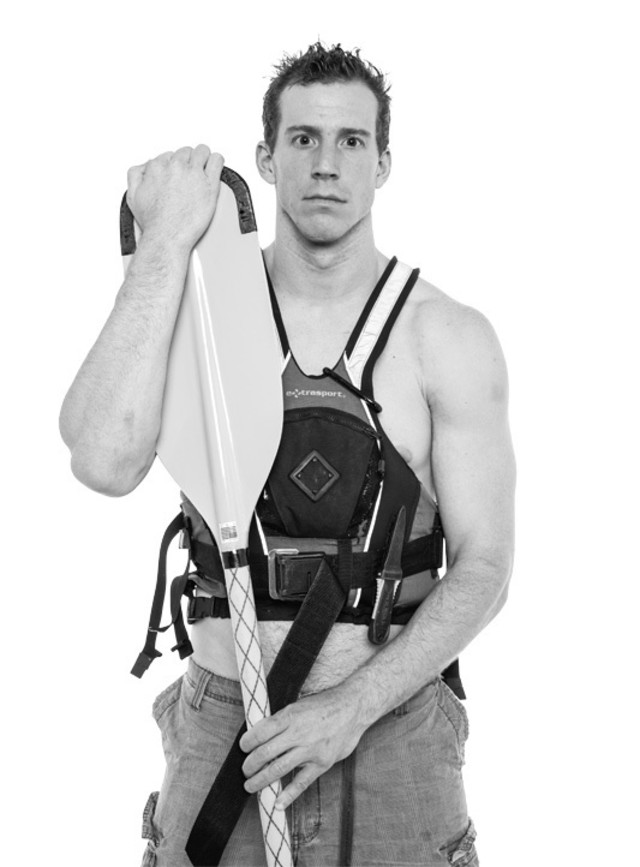

Lane Jacobs // Simon Says

Heavy rain kept the Little White Salmon at record highs for most of 2011, each inch above four feet propelling the river to greater velocity.

“Five feet is super-high,” says Lane Jacobs, a 29-year-old pro kayaker from Oklahoma who moved to White Salmon in 2007 expressly for the Little White, which he first ran a decade ago. “At that level, there’s a good chance of drowning.”

Last spring, with the river churning at five feet, one inch, Jacobs nosed his boat into what may be its hardest rapid: Simon Says, a messy “boulder garden,” a gauntlet of potential unseen dangers. Even the best kayakers usually skip Simon Says.

“I wouldn’t ever call the Little White slow, but high water is quicker,” Jacobs notes. “It’s miles of not knowing what’s around the corner. You have to be so focused, it’s a meditative experience.”

Together with partner (“crew member,” in kayak parlance) Louis Geltman, Jacobs set a new high-water record for the river that day, earning huge respect from many kayakers who dare take on the Little White only when it’s running a foot lower.

“I’ve been paddling the Little White for 10 years, working my way up safely,” Jacobs says. “It’s one of the most lethal sports. When it goes bad, it goes bad quick.”

Brothers Ben and Willy Dinsdale

Image: Stuart Mullenberg

Ben & Willy Dinsdale // Gettin’ Busy

For most Little White paddlers, the ride starts at Gettin’ Busy, a rock-studded stretch noted for crosscurrents and complex switchbacks that require extreme focus and instant reaction.

“If you put in without skills, the river almost immediately provides feedback,” said Willy Dinsdale, 27, a berry farmer with an engineering degree who was born and raised in Salem. The first time Willy (right) and brother Ben, 30, attempted Gettin’ Busy—notorious for sheer hydraulic force that can eject paddlers for a treacherous “swim”—the feedback was unequivocal.

“We didn’t make it very far,” Ben says. “We recovered our gear but had another swim further on.” What the Dinsdales call “feedback”—which on various occasions has entailed a separated rib and near drowning—others might call a warning. They’d learned to kayak just a year earlier.

“We’ve gone pretty hard at it,” says Ben. “It’s a combination of our enthusiasm and general level of willingness to take risks. That’s resulted in a fair share of learning experiences.”

As its fame grows, the Little White attracts more and more paddlers like the Dinsdales—gutsy athletes eager to prove themselves. Their comet-like entry into Class V kayaking means that some Little White paddlers shun the brothers as liabilities. But doing his own thing suits Willy, who admits his kayaking ability, at this point, is “more about force and will.” And experience has done nothing to dim his passion.

“It provides a profound sense of exploration and challenge,” he says. “You’re floating, but it’s like you’re flying.”

“You have one thing to deal with, and everything else goes away. It’s an antidote to the mundane.” - Stephen Cameron

Image: Stuart Mullenberg

Stephen Cameron // S-Turn

On June 16, 2012, veteran kayaker Stephen Cameron, 52, paddled just ahead of crew member Jenna Watson, a 38-year-old seasoned paddler making her first run on the Little White. He admired Watson’s clean lines through Gettin’ Busy, Boulder Sluice, and then S-Turn, a 12-foot waterfall with deep holes foaming at its base, where crosscurrents fold back on themselves with the force of a horizontal tornado.

“Jenna ran S-Turn well,” Cameron says.

Yet as he watched from just feet away, Watson’s boat flipped at the waterfall’s base and was sucked into a cave cut under the water line. For a moment, Watson’s pink helmet was visible; soon, her kayak spit from the cave, empty.

Cameron’s six-member crew scrambled to throw safety lines and call a rescue helicopter from a SAT phone. Bellingham paddler Ryan Bradley—who seven years prior had lost his brother to Class V rapids at Yosemite—dove into the underwater cave. Bradley emerged 20 seconds later with an unconscious Watson. Cameron, a doctor, began CPR. He kept going for two hours, even though within 20 minutes, he says, he “knew it was over.”

Watson’s death provided a sobering reminder that no kayaker, no matter how experienced, can control every variable on the river.

“You have one thing to deal with, and everything else goes away,” says Cameron, a 28-year veteran of the sport. “It’s an antidote to the mundane, but there is real risk.”

Captivated by the sport as an 11-year-old watching the 1972 Olympics, Cameron has seen rapid change. “People used to paddle with motorcycle helmets and fiberglass boats, and they weren’t running anything as hard as the Little White until the 1990s,” he says. “The young studs have to keep running bigger drops, but I don’t know anyone who runs anything as hard as I do for as long I have.”

Cameron and others who were with Watson still don’t know what (if anything) she did wrong. “There isn’t anything fundamental that any one of us would have changed,” he says. “We watched out for her. The water was at a perfect level for a first-time run.”

"Even in-between stuff here would be epic elsewhere." Kayaking roommates Nicole Mansfield (left) and Katrina Van Wijk

Image: Stuart Mullenberg

Nicole Mansfield & Katrina Van Wijk // Horseshoe

Just about every morning, roommates Nicole Mansfield (near right) and Katrina Van Wijk reach for their cell phones. “Little White? Little White?” they text, reaching out to other nomad paddlers passing through the Gorge.

Mansfield, a 30-year-old from Buffalo, got hooked on kayaking at Dartmouth College and has moved seasonally ever since, roaming from Alaska to Colorado to promote her sponsor, kayak manufacturer Pyranha, working short-term jobs on the side. Competing in the 2012 white-water Grand Prix in Chile, Mansfield connected with Van Wijk, a former member of Canada’s national cross-country ski team whose kayaker parents practically raised her on water.

Last spring, they launched a two-person kayak over Oregon’s 45-foot Celestial Falls “to make it more exciting.” No such boost is needed on the Little White. “Even in-between stuff here would be epic elsewhere,” Mansfield says.

That’s especially true at the U-shaped ledge called Horseshoe. Described by one paddler as the “psychological crux of the Little White,” Horseshoe’s jungle of holes leads to a waterfall that has nearly claimed several lives.

Van Wijk plans to return to Canada after Memorial Day weekend. Mansfield hopes to settle into White Salmon life for at least a year—longer than she’s stayed anywhere since she turned pro. When she’s not dropping into the canyon of the Little White, she slings beer at Everybody’s Brewing.

“Some locals understand this hidden little world, what I moved here for,” she says. “Others say, ‘Oh, yeah—rafting!’”

“If you’re a good kayaker in West Virginia or New Zealand, you know about the Little White.” - Dan McCain

Image: Stuart Mullenberg

Dan McCain // Stovepipe

Extreme kayakers have redefined the Little White: from unrunnable to insanity to pro testing ground. Standing out now requires creativity.

“The Little White is not generally considered raftable,” says Dan McCain, 32. “Kayaks are nimble. A raft is more work. But some of the drops considered dangerous are less of a big deal in a raft.”

A sponsored rafter known for buccaneering feats like a 125-foot plunge over a dam, McCain claims his wildest days are behind him. But thanks to the Little White, he can still push his technical abilities. Case in point: Stovepipe—a forked precipice with a dangerous, kayak-eating wall of undercut caves lurking at its bottom.

“You can get sucked under at Stovepipe in a kayak,” McCain says. “But a raft takes out a lot of the danger.”

Some kayakers are unnerved by McCain’s relatively giant rubber raft, now sliding over boulders and bouncing off walls almost weekly. “Dan is the nicest guy you could ever meet,” says Dave Hoffman, a longtime Little White kayaker. “But I’m not sure I want to look up and see a big raft coming down on top of me.”

While McCain would prefer a little more credit for his near-decade of expert raft handling, the Montana native and Oregon State University pharmacy student says he’s fine catching flak as long as he can keep running this “perfect” river. And as far as who can or should be floating their boat on the Little White, he says the current river tribe better get used to newcomers.

“If you’re a good kayaker in West Virginia or New Zealand, you know about the Little White,” he says. “The word is out.”

“You hear a low rumble.... you see the river drop off the face of the earth, and know it’s big.” - Sam Drevo

Image: Stuart Mullenberg

Sam Drevo // Spirit Falls

“When you’re coming up on the falls, you can’t see the cauldron below,” Sam Drevo says. “But you hear a low rumble and feel the energy of the water. You see the river drop off the face of the earth, and know it’s big.”

A kayaker since the age of 8 on the Potomac, Drevo first competed on white water at 15. In 2001, he won the Gorge Games in extreme kayaking. More than a decade later, the hard-working businessman—now 36 and the owner of kayak shops in Oregon City and Portland—spends most of his time on flatwater, preaching the wonders of paddling to a broader audience. But when Drevo gets the chance, he heads for the Little White. The proliferation of boats, which peaks on May 26 with the third-annual Little White Salmon Race, hasn’t missed his notice. “There will probably be 100 kayaks out that day,” he says. “When I first ran the river in 1996, maybe 10 people had ever done it.”

He’s heard scuttlebutt among elite kayakers about discouraging less-experienced newcomers—talk that centers on both river safety and concerns that negative press could shut down access to this international mecca. But Drevo is reluctant to see surfer-style territorial attitudes emerge in a sport, and a place, he still feels is defined by uncommon camaraderie.

“It’s just fairytale stuff here in the Pacific Northwest,” he says. “The Little White can be pillowy, dreamy. I’m OK with bringing the river to the masses, as long as they respect it.”