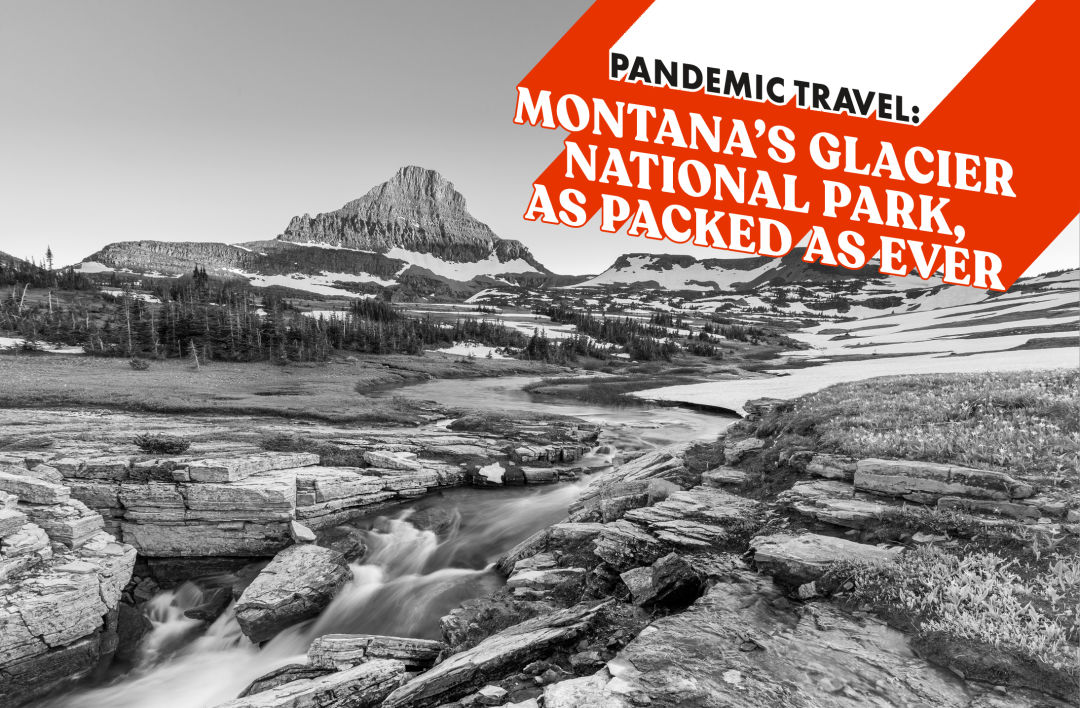

Pandemic Travel: Montana’s Glacier National Park, as Packed as Ever

We all have our own risk tolerance levels nowadays when it comes to leaving the house, whether it’s to exercise, get groceries, visit the dentist, see loved ones, or get to work. It’s no different when it comes to getting the heck out of town. Some of us have been weekending in Vegas. Others haven’t left their zip code since March. And a lot of us fall somewhere in between, including Portland Monthly contributor Jason Notte, who decided to check some nearby destinations off the to-do list after trips abroad were canceled.

Sitting on a fallen tree straddling McDonald Creek, we’re watching the low-slung Sacred Dancing Cascades and absorbing the welcome white noise of its rushing waters. That serene din dampens the footsteps and breaths of the wizened woman who’s suddenly about 10 inches behind my left shoulder.

My wife’s cloth mask of mint-green owls is a fine match for Montana’s Glacier National Park, while my mask’s celestial pattern seems more suited to a ’90s dorm room. Our encroaching visitor isn't wearing a mask at all, which immediately snaps me out of my waterfall appreciation. I ask for some space.

“Huh?”

“Six feet. You’re supposed to keep six feet of social distance.”

A woman beside her posits that, perhaps, she can’t hear me through my mask. Their male companion is less diplomatic.

“Stop being scared of the world!”

My wife advises me to say nothing, though every impulse is to say everything. We’re doing this for her, this older person who’s far more vulnerable to the complications of COVID-19 than we are. And we aren’t even supposed to be here: our original plan had us in Spain for three weeks, traveling to Madrid, Seville, Granada, and back, but a host of refunds and credits from that trip turned into this Montana getaway.

But I say nothing, knowing it’s far easier to let them stumble over the rocky riverbed and out of view than to spend our vacation fighting the battle of McDonald Creek. Besides, as Montana makes evident during our one-week stay in late September and early October, it’s a battle the state willingly forfeits. As COVID destinations go, Montana was perhaps not the best choice: by late fall, the state’s per-capita case count was nearly double that of Spain’s. Just before our visit, reporter-punching Montana gubernatorial candidate Greg Gianforte (a former Jersey guy who’d get clocked right back if he ever tried that with the Hudson County press) had vowed not to enforce mask and distance mandates if elected. (And elected he was, with 54 percent of the vote, though he lost in Glacier County and Whitefish precincts.)

The best choice, of course, would have been to stay home, where despite Oregon’s skyrocketing numbers it still has one of the country’s lowest per-capita coronavirus rates. However, after taking a carefully distanced trip to Crater Lake National Park and the Oregon Coast for a week in July, we thought the pandemic would provide the perfect opportunity to check Glacier off of the to-do list, since it might be less crowded than usual and the rest of our travel to-do list (a tour of European Christmas markets, for example) was definitely off the table for 2020.

The first sign we might have miscalculated was the 14-hour train trip on an almost-empty Empire Builder, several hours longer than the car ride would have been and, between budget cuts and COVID-era changes, lacking the usual charms of train travel. Whitefish, where the train deposited us, paints an unrealistic portrait of Montana tourist life. Businesses strictly enforce mask usage. Several shops and restaurants were closed after employees contracted the virus. On lampposts and in storefront windows, we spotted several fliers warning tourists that the quarantined Blackfeet Nation had closed its border to Glacier, restricting travel to the park’s easternmost attractions. The message was simple: “The Blackfeet Nation Is More Important Than Your Vacation.”

Beyond Whitefish, however, the area’s approach to the pandemic was a bit more freeform. We’d rented a cabin on two acres in Lakeside, a tourist town just southwest of Glacier along the western edge of Flathead Lake. (Portland-based property management firm Vacasa had wooed us with promises of deep-cleaning and sterilization and a guaranteed refund for COVID-related cancellations.) The coffee shop down the hill had fully masked employees, floors with tape markers for social distance, and huckleberry hand sanitizer. It also clearly had regulars, one of whom came in without a mask and was waved in simply by saying the magic words: “Hey, Tom, this is OK, right?”

During our first trip to the town’s lone grocery store, numerous customers wore masks on their chins if they wore them at all. Elderly employees not only didn’t enforce Montana’s face-covering mandate for businesses but used only face shields to interact with customers. About halfway through that grocery run, we changed our shopping list from snacks and beverages to a week of full dinners, just so we wouldn’t have to come back.

Then there was Glacier itself. Overall visitor numbers were way down over the year before, with tourist shuttles and the park’s iconic Red Bus service suspended. But since the eastern part of the park cut off, western destinations like Lake McDonald and Polebridge actually saw increases in foot traffic of as much as 25 percent over 2019. On Lake McDonald’s southern edge, visitors packed the coastline for a fall meteor shower and lined up at its visitor center for ice cream and coffee. Along Going to the Sun Road at Logan Pass, park rangers shut down the viewing area’s parking lot as tourists stalked open spaces. With the road closed at Rising Sun just a couple of miles away, the promise of valley views and mountain goat sightings led to logjams along Logan Pass’s boardwalk trail, packed with vanloads of Mennonite tourists and carfuls from as far away as South Carolina. Though masks were plentiful and were applied as unspoken trail etiquette, being close enough to overhear dozens of college students discussing old Tarantino movies at the trail’s final viewpoint was a reminder that social distance was still something of a luxury.

We soon learned to bypass congested stops and seek out the park’s less-traveled portions—like the goat lick, a series of lime-encrusted stone walls near the Blackfeet Nation border, and Bowman Lake. But the best way to get distance from others was to distance ourselves from Glacier. Just down Highway 2 from West Glacier, the Hungry Horse dam and reservoir offered fall color, shadowy sunsets, and a full-moon reflection from its near-abandoned coastlines and campgrounds. The National Bison Range, a drive-through safari view of elk, antelope, and massive namesake bison 100 miles to Glacier’s south, had been closed by COVID until August and was still largely empty.

On our last day in Montana, we returned to Whitefish and looked around with fresh eyes. At the Great Northern Bar and Grill, bartenders served us from behind plexiglass, food was served from the bar kitchen’s pickup window, and every other table was closed for social distance. At bars and restaurants just up the street, crowds packed in as if it were any other Saturday night. For every pizza shop that made customers wait outside to manage capacity, there was a barbecue place that didn't seem to believe in pandemic-aware seating and a record store owner who thought little of selling the small shop's vinyl without wearing a mask. For each bookstore tacking notes to its door telling white nationalists not to use their shop for mask protests, there was an art gallery where the clerk called visitors’ attention to a bucketload of homemade masks while her own mask slipped beneath her nose.

Unlike my shoulder stalker at McDonald Creek, though, at least she had one.

Jason Notte has been a writer for 25 years. His work has appeared in the New York Times, the Boston Globe, St. Mark’s Poetry Project, and numerous business publications. A New Jersey native, he’s spent much of the past decade married to and traveling with a Pacific Northwesterner.

This article is part of a series. Do you want to share your own pandemic travel story? Email [email protected]