Michelle Nijhuis on Changing the Conservation Narrative

“I think so often we enter the conservation story in its very last chapter, when the species is about to go extinct,” Michelle Nijhuis says. “We just have to start earlier and think of conservation as something that we do with healthy species and healthy populations.”

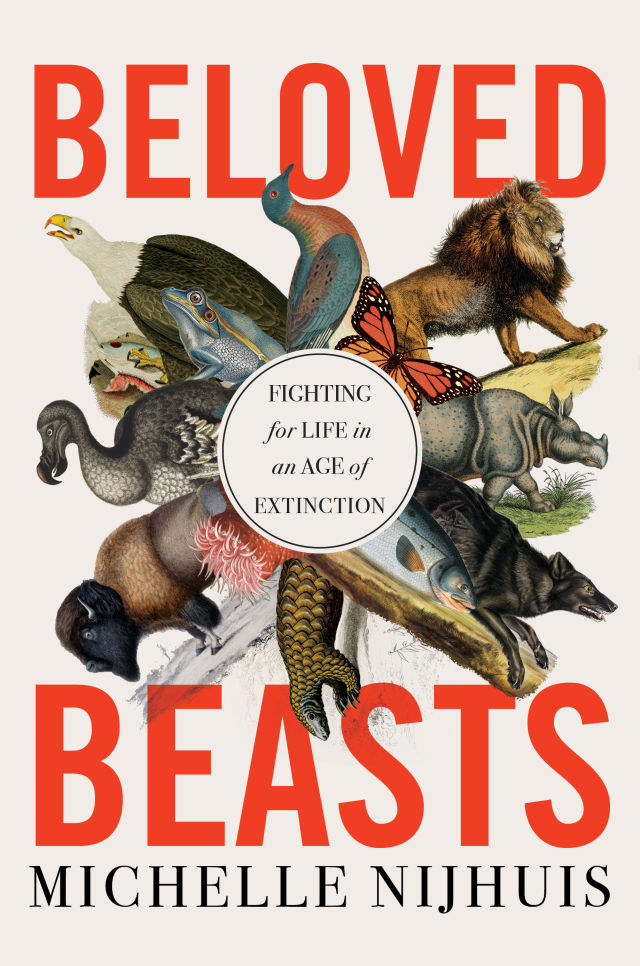

Image: Courtesy Michelle Nijhuis

Michelle Nijhuis has long lived between the fields of literature and science. She loved playing with words but didn't quite like the formal study of literature. She loved animals and nature but didn't quite like the narrowed focus that sometimes defines a biologist's career. After graduating from Reed College in the 1990s, Nijhuis interned at High Country News, and has since had a decades-long career as a science and environmental reporter writing for National Geographic, the New York Times, and more. She's now a project editor at the Atlantic.

Her latest book, Beloved Beasts: Fighting for Life in the Age of Extinction, published by W. W. Norton & Company in March, traces the history of the modern conservation movement through its many vital scientists and activists. The book is an illuminating read, and it details the many ways in which modern conservation is tinged with racism and elitism.

Ahead of her appearance at the Portland Audubon's Wild Arts Festival this Saturday, Nijhuis spoke with Portland Monthly from her home in White Salmon, Washington, about her latest book and how we can change the narrative around conservation.

I’m really interested in your background as a writer because I think it subverts the traditional journalism route. You studied biology as an undergraduate and then started working as a reporter. How did the marriage of those two fields happen for you?

Well, I have always loved writing, and I went to Reed College and majored in biology there because when I started out as an English major I quickly found out that I didn't have much patience for literary criticism, and I was really interested in biology. I hadn't taken a whole lot of science before, but I was interested in the environment, and I found that I really loved learning about biology. At the same time, I wasn't as passionate as I needed to be in a single set of questions to become a biologist, to become a researcher. I think many people who become successful scientists want to know everything they possibly can about one set of things; they spend years pursuing one set of answers. And I think I was wired to be more interested in finding out a little bit about a lot of things and the connections among them.

So I worked for a lot of research projects for several years, and then found my way into an internship at High Country News, which was really my journalism training and my journalism grad school. After I did that internship, I was on staff for four years and I’ve never really looked back.

You spent a few years in southern Arizona and the deserts of Utah. How did your experience in the desert shape your interest in biology and writing about animals and people?

I had a really formative experience when I was at Reed. I took a leave of absence and spent the spring and summer working in southern Utah on another sort of research project. Maybe it was all the vitamin D I absorbed, but I really fell in love with the landscape, just with this openness. I'd never spent much time in a desert before. If you’ve ever been in southern Utah, you know that the geology has this unearthly beauty. I was also just really struck by the size of the sky and then just the people. I was struck by the really diverse assortment of people who come to live in a place like that, that is in a lot of ways hostile to humans, and I got very interested in the politics of overall communities and rural western communities. That’s stayed with me throughout my career.

I lived in Tucson [Arizona] for a couple of years after I graduated from Reed, and that's a very different kind of desert from Utah. In a way it's more lush, but it takes a while to see that lushness if you come to it from a place like the Pacific Northwest. But once you're there awhile you notice what happens throughout the seasonal cycles. You can see just how incredible that place is, how full of life it is despite there being relatively poor conditions, the lack of water and livable temperatures and other things that we normally think of as being requirements for a comfortable life.

Beloved Beasts: Fighting for Life in an Age of Extinction was published in March by W. W. Norton & Company.

In Beloved Beasts you write not only about animals but also about the people who study animals, who try to conserve wildlife—and how some of their efforts have been rooted in elitism or preserving these animals or these places for specific people.

I think, like most people interested in conservation, I knew that there were individual people in conservation history who had said and done reprehensible things. These are things that we now consider reprehensible or even things that were considered reprehensible at the time, but it wasn't until I researched that I really started to think about it as a pattern that continues to hamper conservation efforts.

The modern conservation movement started about 150 years ago, and I would say its greatest accomplishment has been building an international network of institutions that think about conservation across borders. But because it has its roots in elite circles in North America and Europe that were made up of men, mostly white men, it tended and still tends to overlook the ability of people to manage the species they live alongside. I think that tendency to ignore those capabilities is really rooted in the historic racism and elitism and colonialism of the conservation movement.

Happily, I think today's conservation efforts are becoming much more aware of that, and there are emerging movements, worldwide, led in many places by Indigenous people, and I think the conservation establishment is recognizing that as an opportunity and in many ways, embracing it. But I don't want to imply in any way that conservation is a racist enterprise. Nothing can be further from the truth. But in every generation, there have been people who have held racist and elitist attitudes, and I think it's worthwhile for people who care about conservation to face those things head on.

For me, it was very sad but also illuminating to recognize those patterns, and I felt much clearer about what the history meant to people practicing conservation today. My goal was to write a constructive criticism, to put some of these patterns and episodes in context so that all of us who care about other species—which is hopefully most of us—can learn from them.

When we look at conservation today, there's often this foreboding sense of inevitability, but your book is really grounded in histories of the conservation movements, which feels in its own way hopeful, like there is something we can do. How important was it for you to contextualize these movements in that way?

I think this is partly the fault of the media and partly the fault of conservation organizations and their communication strategy, but we've come to think of conservation as preventing extinction. But preventing extinction is just the beginning of conservation. It’s really about protecting relationships, protecting relationships among species, between humans and other species. And that is a much bigger project, and the opportunity to do that is enormous.

I don't want to minimize the problems we're facing, but I think so often we enter the conservation story in its very last chapter, when the species is about to go extinct. And then we say, “Oh, how sad. This is a story of conservation, it’s a tragedy.” But there are many opportunities to change the story. We just have to start earlier and think of conservation as something that we do with healthy species and healthy populations.

You spent 15 years off the grid in rural Colorado, and then moved to White Salmon in 2013. Is there anything from your time living off the grid that you keep with you now?

I loved living off the grid, and I think it was more comfortable than most people often assume that it is. I mean, our family had all the modern conveniences with a couple of minor exceptions. And when I moved to the Pacific Northwest, instead of being outside a small town, we were in the middle of a small town, and I really welcomed that chance to be a part of what I started to think of as the human grid. I mean, it was nice to be part of a tighter community where I could bump into more people and be closer to the grocery store and library.

But I felt that living off the grid, I didn’t like physical isolation of it, but I loved that sense of being comfortable with less and just realizing how easy, comfortable, and enjoyable life could be with a lot less than our culture often tells us we need.

In the Pacific Northwest, are there any conservation efforts you think we should be paying more attention to?

I love what the Columbia Land Trust is doing. They've got an organization in our area called the East Cascades Oak Partnership, which sounds really wonky, and not about a charismatic species, but it is super exciting because it involves an enormous diversity of people who just really love the landscape of the Gorge. They love these beautiful oaks that play such a key role in their ecosystem. They're really accomplishing great things, protecting habitat on public and private lands, there are collaborations among tribal governments and state and county governments. It's really the kind of work that I see as being the future of conservation in that it brings people together and it connects people with their place in a pretty powerful way.