Last of the Big Ones

Image: Todd Pusser

S

omehow, in our examined world, the beaked whale—among the largest mammals on the planet, weighing in around a ton and a half and 20 feet long—has almost always managed to stay just out of scientists’ sight, save for brief, tantalizing glimpses.

But spurred by discoveries made by Oregon researchers, 2022 could be the year we finally fully uncover the giant creatures’ secrets: how many there are, where they like to live, and how human actions impact their survival.

“These are big animals,” says Lisa Ballance, director of Oregon State University’s Marine Mammal Institute. “They’re not planktonic organisms, and we just know next to nothing about them.”

There are at least 22 documented species of beaked whales. One of them, the Hubbs’s beaked whale, was discovered in 1945 and is known to have been seen alive only twice, once in 1994 and once in 2021. Miraculously, Bob Pitman, a 71-year-old marine ecologist at OSU, was present both times.

These whales are so rare, Pitman says, “because that’s the way they want it.” They stay in the dark, deep ocean off continental shelves, where they use echolocation to find their prey. Their calls are too high-pitched for humans to hear without equipment.

Image: Todd Pusser

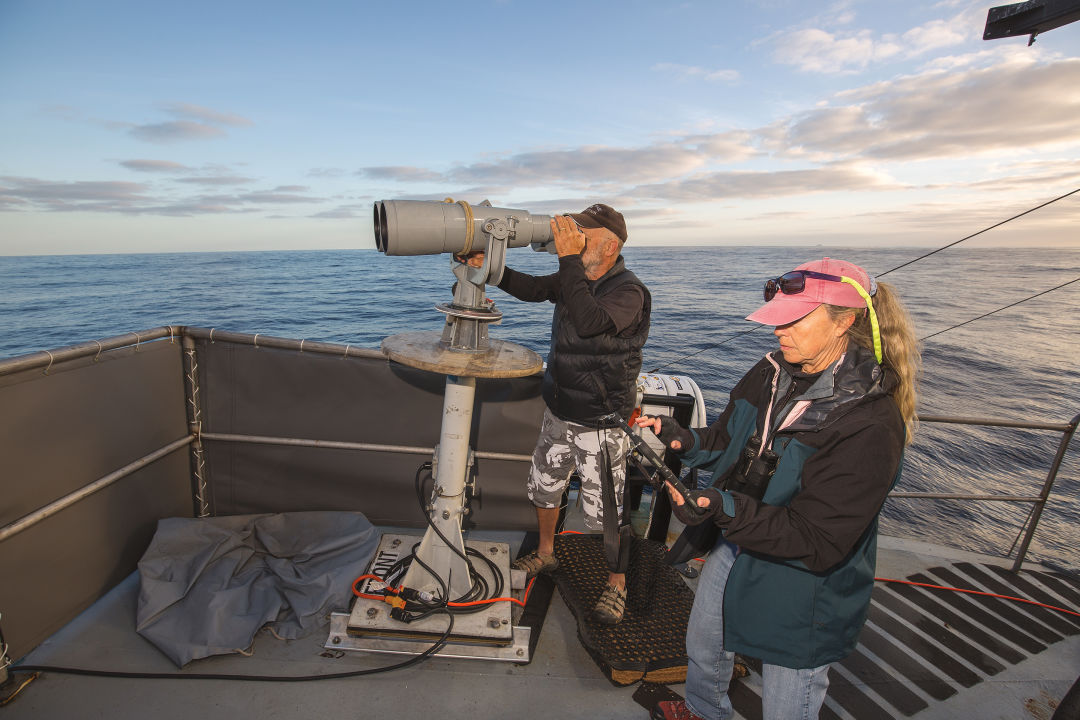

Fortunately, Ballance, Pitman, and a handful of other scientists happened to have that equipment with them in the fall of 2021, when, during a disrupted ocean expedition, they were serendipitously able to record a previously unidentified beaked whale call, take thousands of photos of two juveniles of the species who breached the surface, and even collect a tissue sample.

This is a big deal. Until now, most of what humans know about this species has come only after they’ve beached up and died in areas ranging from Southern California to Vancouver Island to Japan. Scientists couldn’t pinpoint how many different populations of beaked whales there might be or if their range extended across the entire Pacific Ocean. The photos and positive ID sample help unlock those answers.

Beaked whales have been known to beach themselves after manmade disturbances—like seismic surveys—even though they are otherwise perfectly healthy. Armed with the ability to better track the species, scientists can now ensure that they aren’t inadvertently causing their deaths.

The team hopes to eventually set sail again, this time making it all the way to the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, where Pitman says he dreams of spying an even more elusive creature: “a ginkgo-toothed beaked whale, which has never been positively identified alive in the wild.”