TBA 2010: Five Questions with Ronnie Bass

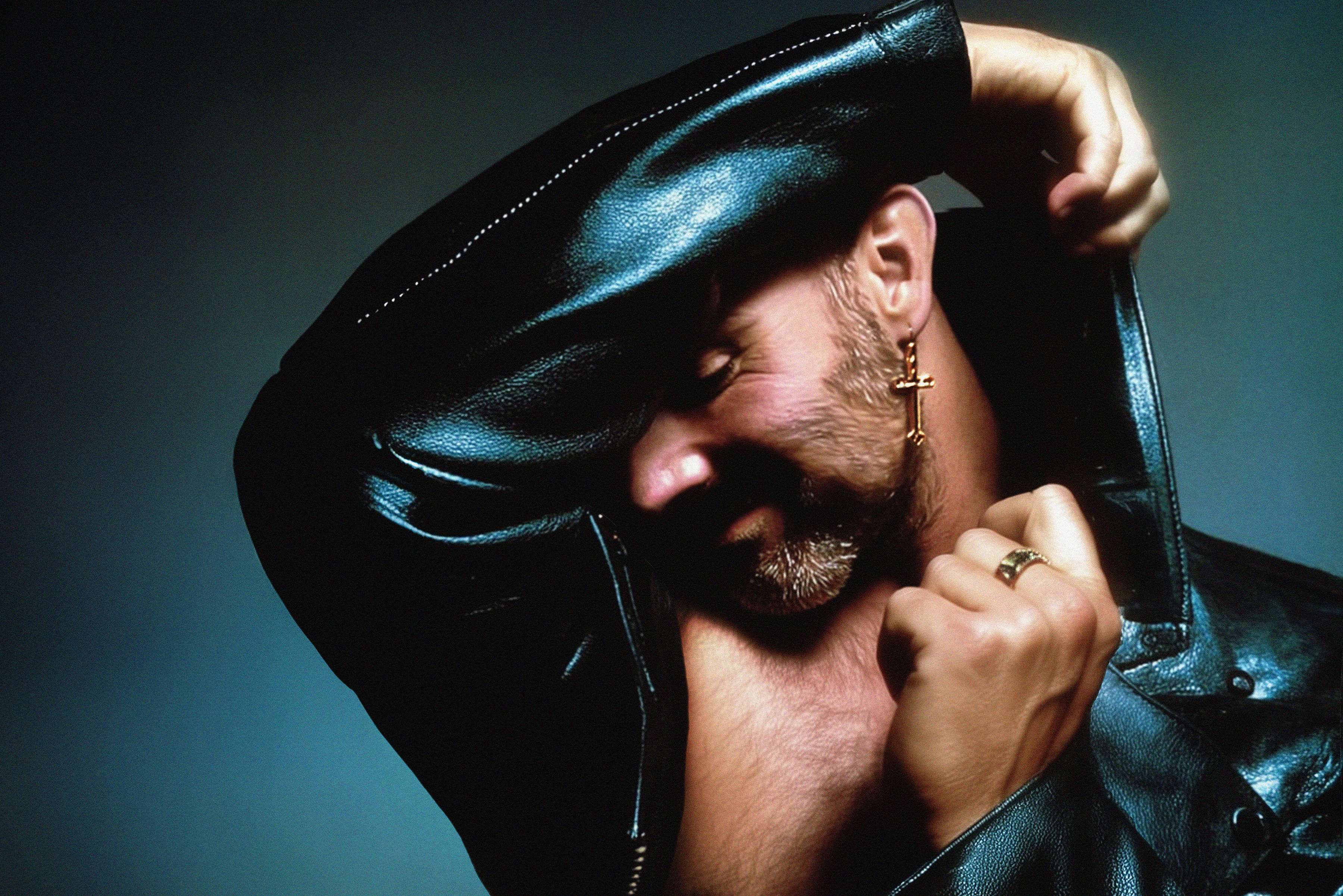

Ronnie Bass gazes trepidatiously through his telescope. Will you come to the closing week of TBA?

Almost a month ago, Rufus Wainwright strode onto the Schnitz stage, kicking off the TBA in a candy-striped velvet coat he’d borrowed from Gus Van Sant. Two weeks later, Blackfish let strains of slide guitar lapse into the Imago silence, to close the festival’s final live performance. But if you thought TBA 2010 was over —au contraire.

Several gallery exhibits at The Works have been open ever since, and will remain through next Sunday, October 17. This means there’s still time to take in The People’s Biennial, and maybe even get answers for the questions it raises in Kristan Kennedy’s special Sunday presentation and walk-through with Harrell Fletcher, David Rosenak and other contributors. You can still behold the bold sapphic futurism of Yemenwed, stroll through Storm Tharp’s High House —or enclose yourself, as I did twice, in the quiet dark confines of Ronnie Bass’s inner-space odysseys The Astronomer and 2012.

As minimal music tensely ticks along at less than one beat per second, Bass holds a conversation with a blanketed form, drills holes in moon-rock, and stargazes at the vast universe from a closet-sized room with a cot in the corner. After enjoying these video visions and his live performance at Drum Machine, I bumped into Bass by The Works’ beer-garden honeybucket. "It’s kind of peaceful in there," he observed. "I don’t think anyone’s used it."

Your songs contain a dialogue between a hesitant voice and a reassuring one—but both voices are your own. Do you think of these as a father and son? Or as one person, parenting an inner child? Any general thoughts on parenting or self-parenting?

I think of the dialogues as being between people, or the ones that I have created. It may be father and son, astronomer and nervous friend or any other variation. The dynamic is always similar: one person has a special knowledge and is consoling someone in need of guidance.

I’m currently working on a project with Tommy Hartung. We’ve been talking about using a disembodied voice via a shortwave radio. One issue that we’ve had is in how to keep the read of the voice as predominantly human without limiting other possibilities.

I didn’t originally think of the dialogue as as a self-parenting situation, but that read makes sense because of how minimally my characters are developed and how one-tracked/minded they may seem. They are almost the simplified representations of internal phases, but that’s also similar to the way that I make my stories, my sets and my scores. I always prefer the essential idea of something over its complex form.

The numbers you cite in your work, fall somewhere around your age—late 20’s to early 40’s. At one point you say, "I’m almost 35 now," and at another you say, "The moon now hangs at 42. If we leave now, we might break through." I’m reminded of Pink Floyd’s "No one told you when to run; you’ve missed the starting gun." Am I right in guessing that your work depicts progress in relation to age?

I have never thought of it in relation to my work, but there absolutely is a thematic connection. You often hear a similar theme in hip-hop, and in social utopian philosophy, especially in that of Charles Fourier. As different as these forms may be, they all discuss a very similar thing: an escape from our current existence of oppression into a new world. Within hip-hop, it’s a world of lawlessness and extravagance. Fourier sees a refined way of labor and life. Waters and Gilmour don’t really depict a result, only the idea of leaving.

I did try to keep the numbers near the 30s to imply planetary alignment; a sign for the right time to act, but it is a coincidence that it corresponded to my age or ages. Beyond my age of 35, which will happen in the year 2012, the rest of the numbers were chosen because they rhymed with the words that I was using: 29 with time, 42 with through…

It seems like the title Leaving The Shed could indicate agoraphobia, shyness, alienation, and/or creative Insecurity. Do you personally struggle with any or all of these?

I have been accused of agoraphobia because I like to work in small spaces. For me, a small space holds the most potential for work and privacy. I think of the time that I’m making art as a hiding-out or as a retreat. My characters have a similar cocooning phase before their great idea or action. Also, within film, a small space (for me) alludes to the optimistic potential of a vast external space elsewhere.

I do have issues with alienation and creative insecurity. It’s part of being an artist.

Do you think you would enjoy actual space travel? Are you fascinated with the real thing, or just the metaphor?

I would not at all want to space travel. I have to make artwork. I am interested in science and technological advancements and space travel fits into that. In The Astronomer, I never thought of their destination as outer space, it is only that a cosmological sign prompted their journey. For me, their destination was an area that they could carve out within a space that has already been scripted with its own order. The optimistic aspect is that they would be able to live independently from, and simultaneously within, this scripted order.

Do you think the world is going to end in 2012?

Two big events are supposed to happen around that time: a giant solar flare and the flipping of the Earth’s magnetic poles. Scientists say that it could be devastating; but my answer is no, I do not think that the world is going to end. The sense of foreboding in my work is coming from my own observations of our current economic and social conditions. Within this nation, I predict a future of class division that will be several times more severe than what is currently occurring. It’s the nature of late capitalism emmeshed with corporatism. I’m not here to fight it or to change it. As an artist, I can only present it and propose questions. Any answers are fantastic renditions.