Review: Cherry Orchard

A penny for Chekhov’s thoughts.

For some, an adaptation of a play, especially one that is an established classic, is foolhardy; any re-write or re-direction simply diminishes a great work. For instance, if Romeo and Juliet suddenly sprang to life at the end of Shakespeare’s tragedy, doing a jig and whistle, we’d feel more cheated than relieved (if not completely bewildered). Adaptation can do plenty of wrong (see: any novel turned into a movie) but it can also cast a classic in an exciting new light (M. Ward’s cover of David Bowie’s “Let’s Dance” springs to mind). Besides, if we clung too closely to “ain’t broke, don’t fix,” we’d be stuck with the same renditions, the same direction and delivery, every tedious time.

This month, LA-by-way-of-NY playwright Richard Kramer world-premiered his adaptation of Anton Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard at “Artists Repertory Theatre”: artistsrep.org/ (directed by Jon Kretzu). Chekhov’s final play, Orchard focuses on a family of disenfranchised Russian aristocrats as they revisit their estate—an exquisite manor with an exceptional cherry orchard—for the last time before it’s auctioned to pay the mortgage. Proud and unwilling to accept advice that could save her land, family matriarch Ruby Ranevsky ultimately does nothing but throw her money away, and the orchard is sold and cut down.

The play’s original Moscow premier left Chekhov dissatisfied to say the least. He’d intended The Cherry Orchard as a comedy, but to his dismay, it was initially staged as pure tragedy. He died within two months, waiving a second chance to troubleshoot his play’s dramatic tone. Kramer’s liberal adaptation features three new characters, including the ghost of Chekhov himself, a contemporary and humorous upheaval of language, and even new bits of dialogue. But do the changes enhance or compromise an already great play?

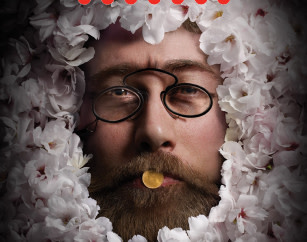

Kramer seems to realize that an adaptation of a play is a spiritual collaboration with the original playwright. Hence, his changes represent a new interpretation, not an entire re-envisioning. Rather than opening, as the original script does, with Lopakhin, a landowner and the Ranevsky’s former serf, and their chambermaid Dunyasha, Kramer introduces a dreamlike sequence in which we see Chekhov’s “ghost” feeding a line to Firs, the ancient family footman. Firs struggles with the line, never quite getting it, and Chekhov grows impatient. As new characters enter the stage, Chekhov bounces around, writing notes, in fact writing the play as it unfolds, and we see that he is invisible to everyone but the audience. Eventually the play “starts” where it’s supposed to, and Chekhov leaves the stage but remains participatory, jotting notes while seated with the audience. Seeing the author offstage could have proven distracting, but in this instance, it added another layer to the action, framing the performance as“Chekhov’s version,” as moment by moment the portly Russian scholar engaged with his creation.

But why put Chekhov in the The Cherry Orchard in the first place? “The more I found out who he was when he was writing The Cherry Orchard the more he seemed, at least to me, to ask to be in it, too,” Kramer explains in the playbill. “No one dies in this play, but Chekhov is dying all through it; he listens to his characters and lets them famously talk, but I also think he hears, like the famous sound of the string snapping in the heart of the earth, the voice of death itself. So I’ve put him on stage, from time to time, living (or dying) the play as he writes it.” Chekhov’s presence is a sly wink-and-nod, especially when Firs finally nails the line Chekhov had been trying to get him say in the very last scene. Scenes and dialogue which Chekhov says to himself appear later in the play, almost at the reluctance of the characters, as if someone was pulling their puppet strings, a la Being John Malkovich.

Kramer also introduces two new characters, albeit without dialogue, that act more as props than plot devices. Their interpretation is open ended, yet their appearance on stage begs your curiosity. Who are these wandering specters? What do they represent? Having never seen The Cherry Orchard before, I thought this was simply a Chekhovian ploy, the usual dismal white-clad figures used to symbolize death or rebirth, or whatever. But they’re actually part of Kramer’s adaptation, a woman and young boy dressed in white, who go about their business like Chekhov’s ghost, equally unobserved. Despite their understated presence, the new figures provide a fresh perspective on the sorrows of the Ranevsky family, as well as the tragedy that awaits them. Like Chekhov, I never felt like they detracted from the story or action on stage. They come and go, and if you want to make anything of their involvement, you can. Thankfully Kramer doesn’t force an answer.

Kramer’s version also substitutes the somber Russian delivery with boisterous American panache. Using his TV writing experience, he takes many liberties with the script, “punching up” jokes for a Friends-like delivery. At times, the play swoons into daytime soap territory, to the point where you almost expecta violin to swell, or a character to lapse into a sudden coma. Russian names even get a simplified pronunciation (“Doe-NAY-shah”).(“When I hear a fancy conversation I want to vomit,” groans Trofimov, the idealistic tutor. Cue panned laughter.) Staunch classicists may scoff, but I’m okay with it, and I feelKramer’s made perfectly suitable modern adjustments, which actually help conform the material to Chekhov’s original preference for a comedic tone.Of course, no matter how it’s treated, the darker side of The Cherry Orchard ultimately reveals itself in the final act—and the buildup of humor only makes the ending that much more fierce and bittersweet.

STAGE Designed to neatly express the orchard and the Renevskys’ childhood manor, the set is simple, and minimal without suggesting too grandiose an estate. Best feature? Water bubbles underneath a double French door that can unlock, allowing access to a stream that’s used in conjunction with an outdoor scene.

COSTUMES Immaculately designed by Darrin Pufall, the wardrobe was absolutely mesmerizing. The Ranevskys drape themselves in lavish furs and swap tailored dresses and suits with every act—heightening the sense of social class and fashion. The humble Trofimov wears a dust-ridden jacket, and mothballs almost seem to flutter about when he walks. The jubilant, if unnecessary, Simon Yepidikoff, wears polished boots that squeak and chirp whenever he takes a step. And the delightful Uncle Leo (Michael Mendelson) is consistently dressed to the nines, replete with waxed mustache. I would let Pufall pick my wardrobe any day.

PLAYERS From Jeffrey Jason Gilpin’s professorial Chekhov, who snaps across the stage, shooting critical glares at family members while scribbling endlessly in a notebook, to Vana O’Brien’s hilarious Charlotta, who enters the estate carrying Miss Helga, a small, nut loving dog, the characters are played with gentle vivacity. Big props to Tim Blough’s Yermolay Lopakhin, whose bushy beard, crazy hair and resounding voice drew immediate comparisons to Jeff Bridges and “the Dude.”

The Cherry Orchard is essentially a topical moral lesson; memory can degrade the truth and blind us, pride can be a relentless, obstructing struggle, and that for all the apparent lessons learned, none of them may make sense until it’s too late. Kramer has intentionally sidestepped the tried-and-true hierarchy struggle—the bourgeois vs. the impoverished—instead examining our common traits, our ambiguous morality, and the absurdity that afflicts us all. Adaptations are a risk, but Kramer’s changes bring new resonance to the play, and pay touching homage to Chekhov. In Kramer’s words: “I didn’t write The Cherry Orchard you’re about to see. I looked at it, lived in it for a while, tried to capture through a blend of Chekhov’s words and my own how it felt, what it meant, what it was. Which is to say: I adapted it.”

Artist Rep’s The Cherry Orchard runs through May 22. For more about Portland arts events, visit PoMo’s Arts & Entertainment Calendar, stream content with an RSS feed, or sign up for our weekly On The Town Newsletter!