Museum Mayhem

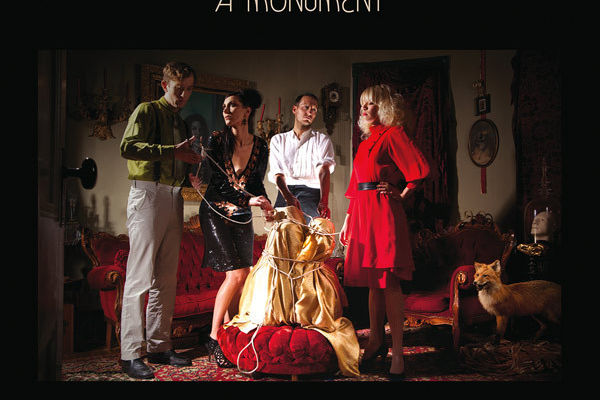

Museum security guard Ted Smith and social practice artist Lexa Walsh “perform” with Philip Guston’s 1969 acrylic, Untitled

Image: Stuart Mullenberg

ON AN AVERAGE Saturday, about 550 visitors saunter through the Portland Art Museum. When there’s a blockbuster exhibition—say, Treasures of Ancient Egypt—figure on 1,500. But last October, more than 2,700 came in one evening. They were there not to ogle the mummies, but to navigate the galleries with compass and topo map, listen to guided tours recorded by security guards, drink art-inspired microbrews, and watch nude wrestling amid Greco-Roman sculptures.

The museum calls this annual funhouse “Shine a Light.” But the Portland State University graduate students who shape the event consider it part of a movement: “social practice.”

Shine a Light got started with the arrival three years ago of Tina Olsen as the museum’s education director. Fresh from the Getty Center in LA, Olsen began reinventing the 119-year-old museum’s efforts to reach teens and 20-somethings. She got in touch with artist and PSU professor Harrell Fletcher, and together they developed the evening as a nearly no-holds-barred artistic experiment. (One rule, no touching the artworks—at least those the museum owns—is still in force.) Says Olsen, “We want the students to take charge in reshaping how people experience the museum.”

Fletcher is founder of PSU’s Art and Social Practice program, the latter a concept as easily grasped as smoke. According to Patricia Failing, an art history professor at the University of Washington, artists who embrace the philosophy rebel against the notion that the end result of art must be a static masterpiece and instead focus on changing individual and public perception of both art and life. The point is not to produce an object, Failing explains, but instead to “create a dynamic community structure”—in short, a group experience. Social practice’s precedents, depending on how you look at it, might stretch from the Russian constructivists’ calls for “Art Into Life” to the quilting bee. But to Jen Delos Reyes, who codirects the PSU program with Fletcher, Shine a Light is simply an opportunity to present unfamiliar art in a familiar museum setting—and to challenge the assumptions about what both mean. “The museum isn’t a place where art objects go to die,” Delos Reyes says. “It’s a place where art can be made.”

Lexa Walsh, a third-year social practice student, is orchestrating several projects for this year’s Shine a Light. For one, she’s designing hairpieces and costumes modeled on paintings and sculptures throughout the museum, hoping attendees will don them. (Those with a bolder yen to participate can have their hair cut and styled to match, too.) She also will write and perform cheers, the kind usually reserved for high school football games, for works in the modern and contemporary art collection, which will function as both homages and condensed art history lessons. She plans to call a square dance, mixing the do-si-dos with exchanges of business cards. Finally, Walsh is working with local chefs to create a “museum cookbook” and solicit food carts to prepare dishes for the event, all inspired by their favorite art pieces.

Inventive? Silly? The beauty remains solidly in the eye of the beholder. “This kind of work can be formulaic or trite without the proper outlook,” Failing warns. “It’s a very different sensibility than what is required of a person sitting in a studio pounding out a little painting.”

The genre has a particularly strong foothold here in Portland. When Fletcher started PSU’s program five years ago, only his alma mater, California College of the Arts, had anything like it. Originally hired by PSU to teach sculpture, Fletcher—nationally known for his own brand of participatory art such as his collaboration with writer-artist-director Miranda July on the global-reaching “Learning to Love You More”—shaped a curriculum to explore new avenues for art and reject the market-based gallery system, which he finds exploitative and unfair to artists.

“Tons of artists have argued with me about this,” he says. “But they’re all just hoping they’re the ones who make it, the ones whose work is going to sell. The chances are slim at best, and artists are totally dispensable."

Indeed, like Walsh, MFA student Jason Sturgill will steer a wide berth from the canvas and the art market. He’s been working with 10 artists to develop more than 20 black tattoo designs based on pieces in the museum’s collection. A pair of tattooists will be on hand to etch the images into the skin of willing visitors.

“In social practice, we talk about art having a lasting effect,” Sturgill says. “This is something that will stay forever.”