Retracing K2's Deadliest Day

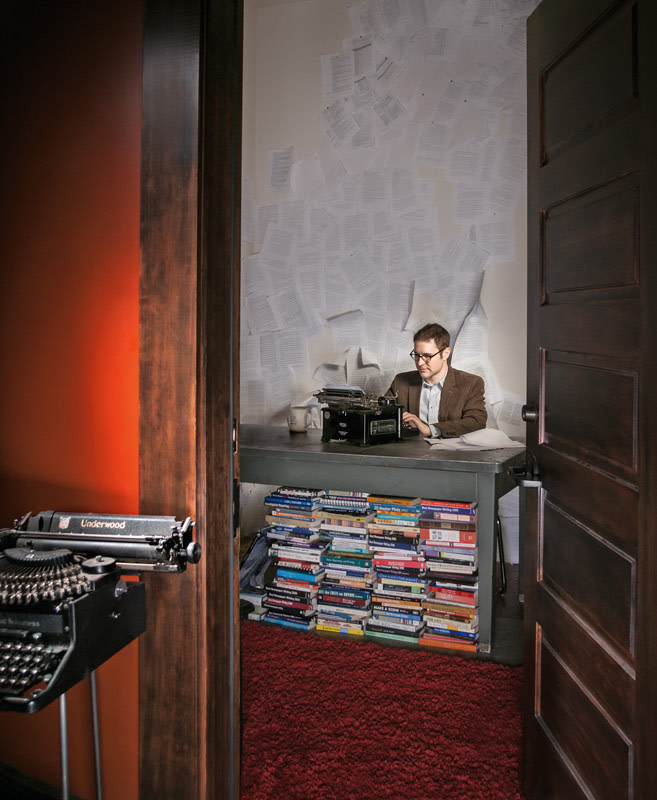

Journalist Peter Zuckerman in his office in the basement of North Portland’s Falcon Art Community

Image: Nicolle Clemetson

IN BURIED IN THE SKY: The Extraordinary Story of the Sherpa Climbers on K2’s Deadliest Day, reporter Peter Zuckerman begins with a literal cliffhanger: in the middle of the night, the Sherpa Chhiring Dorje clings to his ax on an ice wall with another climber, Pasang Lama, tethered to his harness, as giant boulders of ice careen past them. Suddenly, they slip.

But Zuckerman could have started with another high-altitude drama from his own climb to getting the story: an inadvertent, seizure-laced, psychedelic trip on a legendary Himalayan medicinal fungus that erupts from a caterpillar. A two-week hike from the nearest road, he hallucinated heavily while his guides and translators (including Pasang) lay unconscious and convulsing nearby. Halfway through a call to his cousin and writing partner in Los Angeles, Amanda Padoan, to request an airlift, his satellite phone died.

Zuckerman’s own brush with death didn’t make it into his and Padoan’s page-turner addition to the library of great mountaineering books. But the experience steeled his resolve to power through the challenges and doubts to finish a work of incredible reportage that ultimately set off a bidding war among multiple publishers. Synthesizing the accounts of both Western climbers and their Nepali and Pakistani guides, along with extensive historical and cultural research, the book explores the rich histories of the various high-altitude workers before it ascends into a knuckle-whitening narrative of the fateful climb and ensuing catastrophe on K2. The result is a rarity among mountaineering books, which almost exclusively tell their stories from Western climbers’ points of view.

“If you read Into Thin Air, [author Jon] Krakauer talks about the sherpas, but the perspective is very much his and his fellow climbers who were going on a guided expedition,” says Maurice Isserman, an eminent mountaineering historian at New York’s Hamilton College and coauthor of Fallen Giants: A History of Himalayan Mountaineering from the Age of Empire to the Age of Extremes. “What sets apart Zuckerman and Padoan’s book is they really build their narrative around Chhiring and Pasang. In that sense, it’s a singular achievement.”

Zuckerman, 32, traces his sympathy for people brushed aside by history to his own childhood. Growing up in Los Angeles, he was taunted for his learning disability—he suffers from Gerstmann’s syndrome, a neurological condition that causes language and spacial memory problems—and his perceived sexuality. (He didn’t come out as gay until going to Reed College.) Yet the persistent harassment didn’t dampen his irrepressible excitement about the world.

“I think Peter has a crush on everybody,” says Kelly McBride, a leading expert on media ethics at the Poynter Institute for journalists who mentored Zuckerman and fondly recalls him skipping through the institute barefoot. “When I first met him, I don’t think he realized how quirky and far out there he was. I think he does now, and he knows how to tamp it down when he needs to get information.”

Dressed in T-shirt, jeans, and worn cowboy boots given to him by his partner, Mayor Sam Adams, Zuckerman reads more as artist than journalist. In the warren of studios in the basement of North Portland’s Falcon Art Community, his windowless office looks like it just finished a spin cycle: manuscript pages cling to the walls all the way to the vaulted ceiling—leftovers from an installation he made for an open studio event.

But a reporter he is, his first big break arriving right out of school working at the tiny Idaho Falls Post Register. An unidentified source asked him to meet at midnight near a soccer field. Zuckerman didn’t tell his editor, knowing he’d disapprove. (Zuckerman says Idaho Falls makes Laramie, Wyoming, famed for the anti-gay murder of Matthew Shepard, seem like San Francisco’s Castro District.) But the whistleblower led him to a series of sealed court cases revealing that the local Boy Scout council and Mormon church had covered up the activity of least four pedophiles for decades.

The resulting stories incensed much of the small, predominantly Mormon town, including Idaho multimillionaire Frank VanderSloot (now Mitt Romney’s national finance cochair), who took out full-page ads that outed Zuckerman as “homosexual” and speculated that the scout’s exclusion of gay men and Mormon opposition to gay marriage “may have caused Zuckerman to attack the scouts and the LDS Church through his journalism.” Late-night harassments and letter and phone campaigns against him at the paper followed.

“It was really scary,” he says, “and it set me up to realize that oftentimes doing good journalism means exposing yourself to risks you didn’t even realize you were going to face.” His investigation, combined with lobbying work from some of the parents, resulted in the Idaho legislature removing the statute of limitations on child molestation. For the series, he won journalism’s prestigious Livingston Award.

Zuckerman returned to Portland in 2006 for a job at the Oregonian covering Clackamas County. He met then–City Commissioner Adams in early 2008 at Salon Q, a gay mixer, and it was love at first wonk. “I started asking him obscure questions about land use,” says Zuckerman, “and he actually knew the answers. I was impressed by that. Very romantic, huh?” The two registered for domestic partnership last year.

Photo: Courtesy Peter Zuckerman

Zuckerman trekking to Hungung, the isolated Himalayan village of one of his primary characters, Pasang Lama

IN AUGUST 2008, while Zuckerman reported on the suburbs, some 6,500 miles away disaster struck on K2. Having waited all summer for a clearing in the weather, a number of international expeditions decided to pool their resources and attempt to summit together. Mishaps and miscommunications slowed their ascent. (The Western climbers failed to realize that their Nepali and Pakistani porters spoke different languages.) Ignoring standard safety practices, they pushed to the summit perilously late in the day. As night fell, many of the climbers got lost in the dark. Exhausted and oxygen-deprived, several spent one and even two nights in the high-altitude Death Zone trying to find their way down. After cases of abandonment and of extreme heroism and sacrifice, particularly by the sherpas, the final death toll hit 11.

Zuckerman’s cousin, Amanda Padoan, watched the catastrophe unfold from San Diego. An avid climber, she had previously scaled nearby Broad Peak with one of the sherpas who died on K2. “He had carried a lot of my gear up the mountain,” she says. “And I was starting to feel the weight of his story, so I wanted to write about the expedition from his perspective.” Still nursing her infant son, she approached Zuckerman in late December. Having been childhood writing partners, they decided to rekindle the relationship: she’d provide the mountaineering knowledge, and he’d do the in-the-mountains reporting. Four weeks later, he took leave from the Oregonian and boarded a plane. (The timing worked well in another way: the revelation of Adams’s relationship three years before with a young man named Beau Breedlove made working in the newsroom awkward for all.)

As Zuckerman expanded the scope of the book to include all of the Nepali sherpas involved, as well as the Pakistani porters, he quickly discovered there’s reason beyond lingering imperialistic disregard that few writers include their perspectives: sherpas are incredibly difficult to track down. Many live in remote villages, speak different languages, come from rival ethnicities trying to pass themselves off as the Sherpa ethnicity (which lends its name to the sherpa job description), and are named after the day of the week they were born, meaning thousands share the same name. After several weeks, Zuckerman found Chhiring and Pasang, who in turn led him on multiweek treks to meet other K2 sherpas, including several of Pasang’s cousins.

Photo: Courtesy Peter Zuckerman

Zuckerman’s cousin and writing partner, Amanda Padoan (right), with a group of women in Pakistan during one of their reporting trips

On the trek back from Pasang’s isolated village, in a region forbidden to foreign journalists because of Maoist violence, they came across a small stump of a man selling the legendary caterpillar fungus yarsagumba (or “Himalayan Viagra”). Claiming it had miraculous properties, his guides insisted they try it. No one expected the ensuing psychedelic journey, which they blamed on a bad batch. Just as they started to sober up three days later, the vintage Soviet helicopter of questionable air-worthiness that Padoan sent found them, and the corkscrewing return to Kathmandu became its own bad trip.

Later, tracking down the Pakistani high-altitude porters was a different challenge. Although he could reach their villages by jeep, Zuckerman, on this trip joined by Padoan (who went back several times for further reporting), was often within earshot of Taliban rockets and warnings of locals who freely said Daniel Pearl caused his own death by traveling to the area as a Jew—almost as dangerous as being gay. (In conversation, the Jewish Zuckerman called himself Catholic and “Sam” quickly became “Samantha.”)

While Padoan calls her collaborator’s reporting courageous, Zuckerman himself prefers to focus on the book’s central question: What if you were the climber with the ax in the cliffhanger? Would you have done what most everybody else did on the ice wall and passed by the axless stranger? Or would you have hooked him onto you—knowing that if he fell, you would, too?

“Some of the Western climbers were hostile to the idea of giving sherpas credit on the same level as Western climbers,” says Zuckerman, who gets incensed at the overt yet often unconscious racism of the industry. “But when you fail to see the complete story, you fail to learn from it. When your life hangs by a knot, you need to know who tied it. When you’re putting together a team, you need to know whether these people speak the same language. The sherpas of every story matter because our lives depend on them, whether we know it or not.”

Zuckerman will speak at Powell’s on June 13 at 7:30.

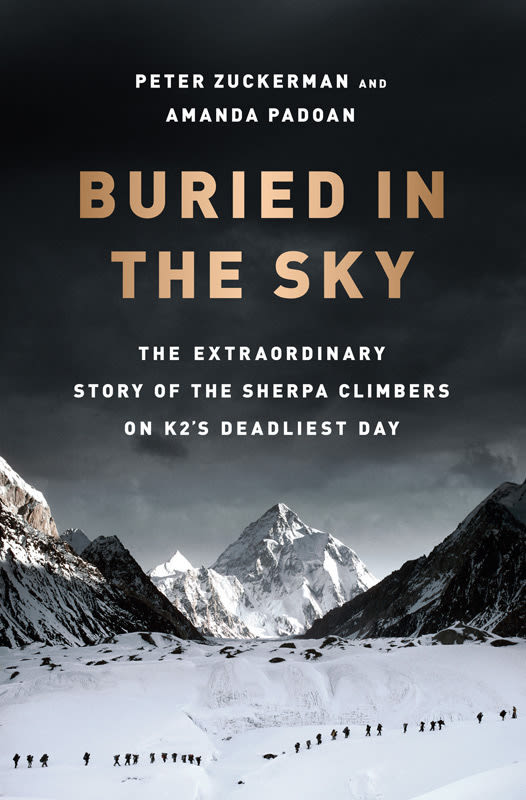

Buried in the Sky

Peter Zuckerman & Amanda Padoan

Norton

262 pages

$26.95