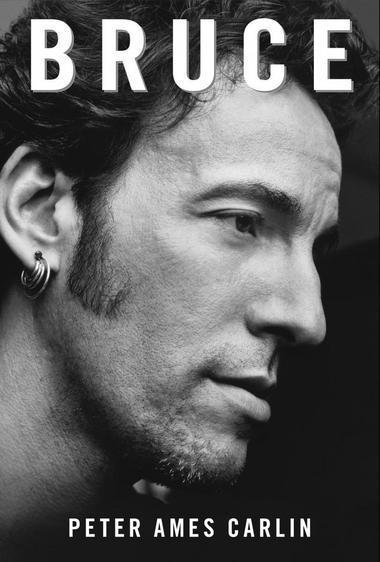

Q&A: Peter Ames Carlin on his Bruce Springsteen Bio

In other words, Carlin’s lived any diehard music fan’s dream: he’s gotten to spend immense amounts of time with his idols learning what makes them tick. In the case of Bruce, he got a year and a half of unfettered access to Sprinsteen, his band, and his family to report on the life and the childhood that has thus far been shrouded myth.

Given that the boss has influenced just about everyone to follow who’s held a guitar, Carlin is getting a book launch like no other. On Tuesday, November 27, a slew of local rockers, including Storm Large and Corin Tucker (formerly of Sleater-Kinney and now fronting her own band), will fill Mississippi Studios with Springsteen covers to celebrate the book’s release.

We spoke to Peter over the phone recently to discuss inner fanboys, his experience writing about rock 'n rolls legends, and getting Springsteen to talk about the childhood he’d never discussed before with the media, like his father’s bipolar disorder.

Culturephile: You worked as journalist for many years at both the Oregonian and People magazine and have seen your work go in many different directions. Bruce is your third major rock bio. What got you on the path to writing exclusively about rock 'n' roll icons?

Peter Ames Carlin Music has always been important to me and I have always been, to varying degrees of competence, a musician. My family, especially on my mom's side, is very musical. Both my grandparents were concert pianists. I got exposed to it super early as a little kid so it's always just been a very important presence in my life. I bonded quickly with certain bands and musicians, and essentially those are the guys I'm writing about. My first love was the Beatles. [I remember] being completely wrapped up in them when Revolver was the new record and hearing my parents playing it.

I've been swept up in Brian Wilson's life and career since I was about thirteen, so around 1998, when I was at People and Brian had a new record coming out [Imagination], I thought, "this is my time, man," and pitched a story about him and convinced my editors to go off and report it myself.

As I got older, I began to think of Brian and other musicians as belonging to the same tradition of your Stephen Fosters and Herman Melvilles and John Steinbecks and Mark Twains: distinct American voices that tell really important stories and interpret what the common American experience is. And so I got to know Brian and his wife, and over the next few years I wrote a story in the New York Times and a couple of big magazine stories and managed to convince somebody to let me do a biography. At that point, I got to spend a whole lot more time around him and just tell the story I thought needed to be told.

There were elements of tragedy in Brian's life that were easy to get enraptured by because they are so resonant in the larger American story—his struggle over the years to make his voice heard and be creative against a commercial current [pushing him] in the opposite direction. I thought his legacy had gotten twisted and wanted to reconcile his popular legacy as a hit maker with the Beach Boys—all the surfing and fun—and unify it with his far more creative stuff and the darkness that has sort of hovered around the guy and compromised his ability to create.

To an extent I did the same thing with Paul McCartney a few years later. That was a little more frustrating because I didn't get any real access to Paul. But it was the same thing: reconciling the pop artist who makes people cringe and the astonishing guy in the middle of the Beatles who changed the world in a half dozen ways.

Both Brian Wilson and Paul McCartney are shrouded in layers of rumor, speculation, and myth. On the other hand, Bruce Springsteen's folklore lies in his image of being Everyman. Do you feel that, as a writer trying to capture the essence of the American experience, Bruce is somehow telling a version of your own story?

Oh yeah, definitely. I saw Bruce for the first time when I was fifteen in 1978, on the Darkness from the Edge of Town tour. I had bought that record, had been aware of some of the songs on FM radio—I probably knew at least half of the Born to Run album just from osmosis—and knew he was supposedly a great performer, but what I didn't anticipate was the amount of emotional power that went into it. I mean they're very fun concerts, but when he's playing serious songs and really biting down on something, he's up there living and dying by every word said and you just didn't see that in 1978.

There's always a certain amount of Hollywood B.S. with touring pop bands: it's a game, it's a show, and you put it on. But Bruce is always tearing shows apart and putting them back together in different ways. And so I was immediately, viscerally moved by the guy and became a teenaged fan.

As I got older, and had worked as a writer and a critic, and spent a whole lot of time thinking about art and culture and history, I became much more intrigued by the distinctions between the functions of imaginary Bruce and the real guy. Because there’s just nothing straightforward about this guy at all and there never really has been. I think people like to see him as—especially as a result of the "Born in the U.S.A." moment where he kind of became this cartoonish, working class superhero. But I didn't have to listen to his songs very long to figure out that there’s a lot about this that’s really fucked up and that there's a lot about this guy who's really in a world of pain. He's voicing it through these characters in these songs, but you don't think these thoughts or get into this headspace unless you've been crawling through some dark nights of the soul.

When you uncovered some of the more unusual circumstances surrounding Springsteen's upbringing, were you excited to have perhaps found a crucial piece in your puzzle?

All I knew [about his childhood] was what I'd learned in the media, and the media so far was incomplete and inaccurate in a lot of ways. Not because reporters were lazy, but because Bruce wasn't tellin'. In the sense that he was telling, he was fudging around with it and sort of reshaping it to fit the narrative he wanted to tell about himself at that point.

Over the years he's created and recreated his own kind of legend of himself. As he's evolved, the story has evolved, and he's always kept a lot of it to himself. But for whatever reason, I came along at a time when I had done a certain amount of work—or a whole lot of work—and he began to feel like he had to take me increasingly seriously. So by the time I was at the point where [his family and his management] were cooperating and it was time to talk to Bruce, I think a lot of why he was willing to talk to me and why he was allowing me to interview parts of his family who had never really been interviewed before was because he wanted to get it straight.

He didn't see you as a conflict to his own revisionist tendencies?

No, I was aiding and abetting, essentially. Our purposes were just miraculously in harmony with one another because I wanted to give an honest and unsparing account of the guy's life and he was ready for that to be written down. He was all in. Anything I wanted to look into he was basically okay with—except to the extent that it might hurt a family member.

Bruce has spent decades writing songs about his relationship with his dad and thinking that the basic "father-son generational conflict" was their problem. He had a problematic relationship with his father, but so did everybody in the baby boom era—or any other era. The kid grows up and has ideas of his own and his dad has a problem with it. Cut your hair or whatever. But in Bruce's case, he'd never really acknowledged—because it was very unacknowledged in the family at least in terms of speaking its name—that his dad had a really serious mental illness. He was bipolar. And mental illness has sifted down through generations of that family.

I was talking earlier about the haunted quality in a lot of his songs. I think it took him a long time to come to terms with that, or at least to think and talk about it in a public space, but by the time I was talking to him it was game-on. I'd written about psychology before—my father was a psychologist—so I think I brought with it a relatively thoughtful and well-informed set of ideas and maybe that made it easier [for him]. He was ready to open up.

And I knew the more I talked to people, before I talked to Bruce, there was just tons and tons of stuff that had never been reported. Somehow I kept moving forward, kept dialing the phone and going to New Jersey, wandering around and talking to people and doing the reporter thing.

As a biographer whose amassed a significant body of work, what remains your biggest fears while working?

There's something very blessed about my life in that I've gotten to know and spend a lot of time with two of my childhood heroes, people who are up in my personal pantheon of demigods: Brian Wilson and Bruce. I respect their work so much. I think I've always been pretty good about not idolizing people as individuals—Bruce always said, "trust the art and not the artist"—so I try to not get too wrapped up in someone's image in a naive way. The problem when you get to meet and hang out with Brian Wilson or Bruce Springsteen is the significant process of reconciling who you expect them to be with who they really are.

To avoid any potential pitfalls in interviewing a personal idol, and experiencing the anxieties that necessarily go along with that, do you consciously frame yourself to these subjects as operating within the bounds of total detached journalism?

The crucial thing is to take your inner fanboy and lock him up in a cage. You can't establish a relationship with this person if he or she intimidates you. If you're Brian, you live in a freakshow. You're consciousness is a circus sideshow full of bearded women and scrawny strongmen and three card monty dealers and ripoff artists and people who will run you through with a sword. That's his day to day life: that's where he is TODAY.

Bruce is way more socialized. It's way more important to him to be a part of the community, so he's psyched to be in the company of other people. He wants you to treat him like he's normal. He's just a regular guy. But he also knows that he's "Bruce Springsteen" and can take advantage of that when he needs to. There were moments when we got into that journalistic "push-me-pull-you" thing where I was trying to get him to explain why his interpretation of an event was so wildly different from everyone else in the room. And he wouldn't want to go there or he'd want to shrug it off and I'd have to go back and—gently and inoffensively—push him around a little bit.

You need them to be honest, but if you alienate them you're done. Once you become a pain in their ass it's like, "we're through here." So there was a part of me that was concerned with having to spend the rest of my life knowing that Bruce Springsteen is mad at me. Or that Bruce just demonstrably doesn't like me. It would take me a while to get back into his work after that.

Peter Ames Carlin will appear with a slew of local rockers in celebration of his new biography and the music of Bruce Springsteen on Tuesday, Nov. 27 at Mississippi Studios. Tickets and info here.