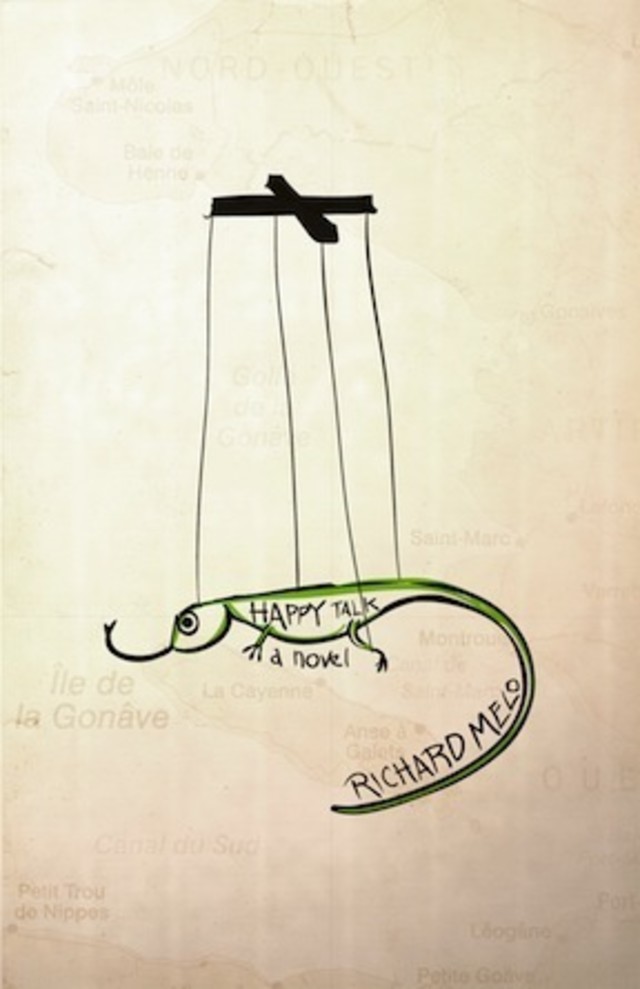

Q&A with Richard Melo, Author of 'Happy Talk'

Portland-based wordsmith Richard Melo first garnered attention from the indie-lit world with the release of his first novel, Jokerman 8, which followed a group of radical environmentalists as they made political mischief. Melo is back with his newest novel, Happy Talk (read our full review).

Set in 1955 Haiti, the novel combines nurses, voodoo, NYC-film students, zombies, Egyptian phantoms, the Nation of Islam, and street theater. Culturephile wanted to know how Melo schemes up these outlandish scenarios, why so many creative call Portland home, and what he’s we can expect from him next. Here’s what he said.

Where did the idea for this novel come from?

Happy Talk is a novel full of minor characters playing major parts. I drew the book from 1960s postmodern novels that featured characters who were often more alienating than endearing. My own tendency is to want to create emotional connections to the characters as much as possible, which might just make me a lousy postmodernist.

Why Haiti in the 1950s? Why voodoo?

I'm always on the lookout for material that might flourish in a novel, and idea of unwitting Americans channeling voodoo spirits seemed to have limitless dramatic (and comic) (and cosmic) possibilities. I was inspired mostly by Maya Deren's study of Haitian voodoo and dance in The Divine Horseman, as well as William Gaddis' brilliant, dialogue-driven novel, The Recognitions, which was published in 1955. These were not works that I could just read and put away on a shelf. I had to do something. I’m not a scholar or an academic, but I can write a novel, so that’s the direction I took.

Richard Melo

Powell’s City of Books

June 25 at 7:30 pm

What was your research process? Did you travel to Haiti? Or were you just practicing voodoo on your own in your office?

As much as I would have loved to see this world firsthand, I never traveled. Instead, I studied photos of northern Haiti in vintage National Geographic magazines, I read musty travel pamphlets (which I then rewrote in a heavily exaggerated style), and I spent many nights on the couch watching 1950s movies trying to get a sense of how people spoke back in the day (even if distorted by the Hollywood lens).

Tom Wolfe believes that novel writing should be like journalism and rely on in-person reporting, and I see value in that kind of work. I’m on the opposite end of the spectrum, though, and lean more heavily on my imagination than personal experience. With that in mind, my writing technique is quite a bit like practicing voodoo.

What is the craziest travel experience you’ve had?

I was stuck in a blizzard in Amarillo, Texas just before Christmas in 1997 and everywhere I went, there were public service posters and billboards showing the faces of Amarillo’s most wanted. I had to rely on the kindness of strangers during the two days I was stranded to get my car back on the road, and many of the people willing to give me a hand were easily recognizable from those ubiquitous posters and billboards. I think the experience taught me quite a bit about the nature of humanity. At the same time, I’ll never again let myself get stuck in an Amarillo blizzard.

How did you conjure these outlandish characters?

It’s like when Jack Kerouac says, “The only people for me are the mad ones." That’s where I start. Novels thrive when they show characters at their most manic, eloquent, genius, hysterical, compassionate, and downtrodden. While the characters in my first book were based on people I knew in college, Happy Talk mostly consists of characters from various source materials (then filtered through people I know). The dastardly Doctor Bast, for example, is a combination of the voodoo figure Baron Samedi and Angelo from Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure—as well as a professor I had once at Portland State.

Some of your group characters (like the Nightingales) seem to function as a single individual, or at least an unindividuated flock. Why?

I'm fascinated by ensembles, movements, and the group mind. It feels like it’s still relatively unexplored terrain in fiction. When I wrote my first novel in the first-person plural "we" voice, I had no idea how rare that was. When it came to writing dialogue for the Nightingales in Happy Talk, I often didn't identify the speaker. In a novel where the dialogue carries the story, it seems less important to know who’s in the room than what’s being said.

Is there any significance to the story being set in the Cold War era?

The Cold War ended so long ago now that people born after it was over are old enough to drink. It's become great material for storytelling because it’s filled with hot button issues that no longer incite the same level of passion. Looking back on the Cold War now, you mostly just see story. The sad legacy of the Cold War, and a connection I hope Happy Talk readers make, is that long after it ended, the paranoia and fear are still with us.

Your first novel, Jokerman 8, was about radical environmental activists. Happy Talk has a similar political undercurrent. Do you think it’s important for books to be political?

I see the novel first and foremost as a form of entertainment. The challenge for the novelist is to find material with substance and make it entertaining. While political issues might come across as vapid when portrayed in the mainstream media, they provide terrific, substance-heavy material to the novel writer. If I didn’t write novels with political undercurrents, they wouldn’t be true to my sense of the world, and I would lose interest in writing them. That said, I see my books as more of a dialogue among competing viewpoints than a diatribe. The views I hold dear don’t always win the day, even in my own work.

What draws you to satire? Are you able to get at something with humor that you can’t in another form?

It’s funny in a way how much of my personality and opinions were formed by music and comedians. I can’t play or write songs, but I can tell a joke, sort of. The secret of humor is that since it doesn’t take itself seriously it can be sneaky.

Do you consider yourself a funny person?

Of course, I would like to think I’m funny, but I can already hear the sound of eyes rolling when people I know read this. I’ve been accused of making too many jokes when the situation calls for moderation, so I'm working hard on my outward gravitas. Over the course of my life, I am running a huge laugh deficit, laughing more at other people’s jokes than people laugh at mine. I have a knack for setting up other people to score the big punch line. I wouldn’t trade that for anything.

What’s next?

I'm already four years into a new novel that revolves around cults, political radicals, and rock 'n' roll— three things that connect in strange ways. It has Scientologists sailing the high seas, members of Up With People plotting to break the Manson Family out of prison, undercover FBI agents surveilling a nude beach, Bigfoot impresarios pranking a UFO convention, and plenty more. People who read Happy Talk will find the logic of it all, and why yes, I’m having fun.