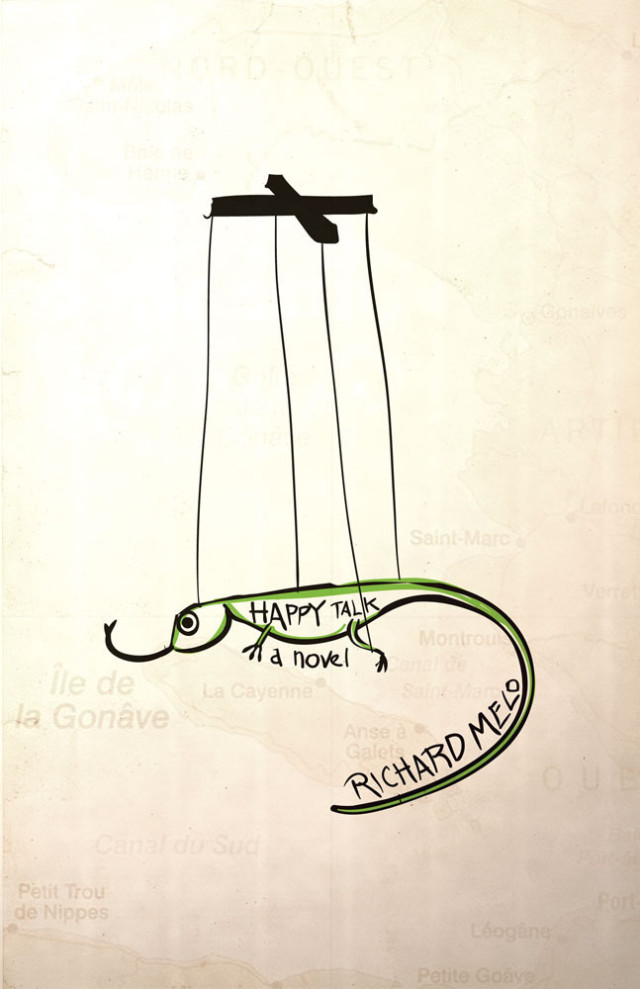

Review: 'Happy Talk' by Richard Melo

Image: Courtesy Red Lemonade

Talk about an electric Kool-Aid acid test. Happy Talk, Portland writer Richard Melo’s new novel, is a laced tropical punch that’s one part Keseyan countercultural freewheeling, one part Beckettian absurdism, and at least a part and a half antiestablishment satire in the tradition of Joseph Heller.

The sophomore novel—Melo’s 2004 debut, Jokerman 8, spent several weeks on top of Powell’s small-press list—is set mostly in cold war–era Haiti and centers on two groups of Americans on parallel State Department missions. The “Nightingales” are a flock of nursing students who haven’t learned much more than how to make beds. As graduation day comes and goes, these chatty nurses start to get suspicious: Have the bureaucrats simply forgotten them? Or might their exile have something to do with the dreaded Bomb?

Meanwhile, the “Useless Bums,” a movie crew, arrive on the island with a directive to shoot a tourism-boosting film about the new fad of surfing. The Department of State wants to make Haiti the next Hawaii, but there’s one small problem: there are no waves.

Like the Bums’ and Nightingales’ missions, Melo’s plot doesn’t have much direction. No matter: as Happy Talk’s caricaturesque characters circuitously navigate the book’s surreal scenarios, their author conjures an atmospheric, dreamlike vision of Haiti and bushwhacks to its conceptual heart. The island is a representation of deep Western fears—something to do with voodoo religion, zombies, and teeming, irrepressible nature. “It’s not the Communists we fear in Haiti, oh no!” says one US agent. “My suspicions about Haiti are spiritual in nature.”

“Some say crossroads split the world in two.... One side is the material world, the other the realm of the Invisibles, and Haiti is one of those rare places on earth where mortals such as ourselves are always crossing over.”

—Page 176-177

Melo has a real knack for dialogue. His characters’ repartee is as vivacious, comedic, and period-perfect as a Billy Wilder picture—but more nonsensical. In one typical exchange, a pair of Nightingales discuss whether invisibility could be verified. “It’s possible, I believe, for a man to turn invisible, but not possible to see him,” one reasons.

At times, Melo stretches Happy Talk’s surrealism beyond relatability, and the extended epilogues flounder. Yet, these aren’t so much failures as indicators of the author’s grand, and mostly fulfilled, ambitions. With Happy Talk, Melo has created an original, vivid, and funny work that is as intoxicating as a voodoo witch’s brew.

Related Article: Q&A with Richard Melo, Author of 'Happy Talk'