Portland Monthly’s Best Books of 2025

Image: N.Savranska/Shutterstock.com

Comparing the best books written by Oregon authors with a list of the best books produced throughout the entire country is sure to have a large overlap any year, but especially in 2025. Why do so many of the country’s biggest writers live here? Some grew up around Portland; some wound up here; most stick around. Whatever the lure is to this place, the writers working here share in their belief of what the world needs right now. Across memoirs and novels, children’s books, a reported dive into wellness cults, a takedown of American mythos, and even a collection of New Yorker cartoons, Portland books this past year championed empathy and solidarity in the face of oppression, whether political or social, new or old.

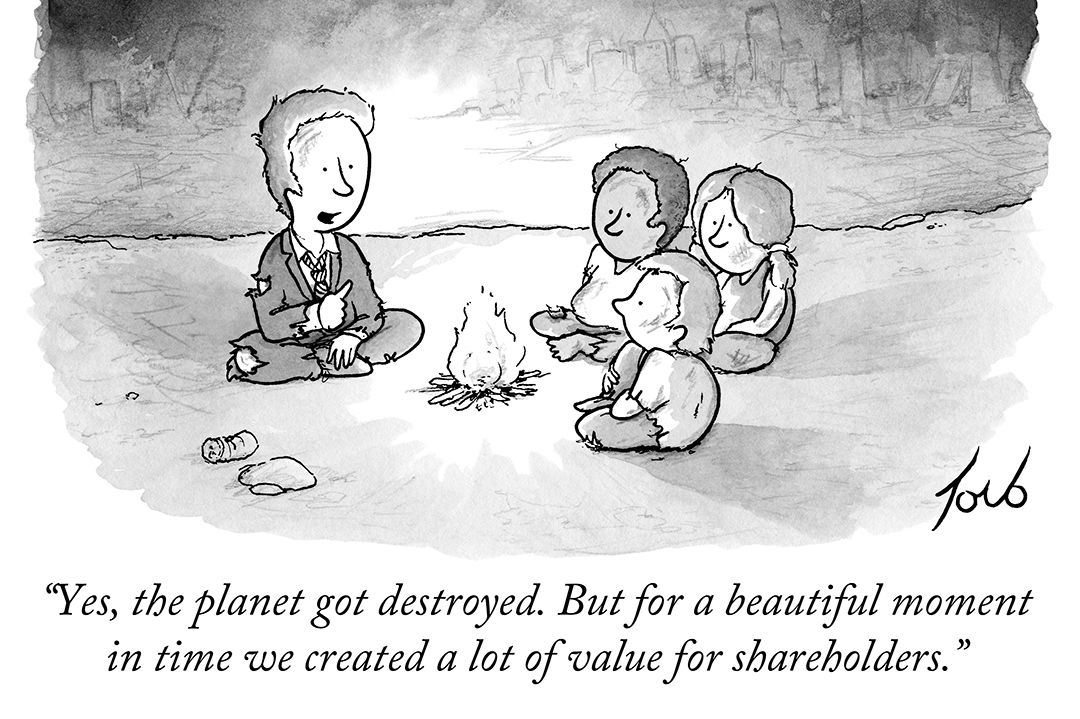

And to Think We Started as a Book Club...

by Tom Toro

Over the past 15 years, Toro has honed his voice within the vaunted cartoons department of The New Yorker. Once comic relief for 10,000-word articles, the specific brand of illustrated jokes is today the intellectual-ish end of a spectrum in our memeified world. And to Think We Started as a Book Club... (Andrews McMeel Publishing) collects the best of Toro’s work. In his biggest blockbuster, a man tells his kids about “shareholder value” while sitting in the shadow of Armageddon. Another is about Adam and Eve being bored (leaves cover Adam’s feet in another; he's self-conscious about them, too). But Toro’s sharpest observations are often the most pedestrian: banter between cowboys, angels in heaven, the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse.

Read our interview with Toro on And to Think We Started as a Book Club....The Antidote

by Karen Russell

Russell’s 2011 debut, Swamplandia!, was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. Her long-awaited follow-up, The Antidote (Knopf), was a finalist for the National Book Award. It’s a witchy Dust Bowl epic set in the fictional town of Uz, Nebraska; the biblical allusion is no accident. With the wry wit and magical realist sensibilities that animated Swamplandia!, Russell’s ensemble cast converges around a “Prairie Witch” or “vault” in whom customers can deposit their deepest anxieties and darkest memories, relieving themselves of the knowledge entirely unless they make a withdrawal. The group includes a Black woman who’s a New Deal photographer, a corrupt sheriff, and several generations of Polish immigrant farmers. In this panorama, Russell captures the selective remembering so foundational to America’s origin story. With curious and empathetic attention, she manages to present a hopeful alternative to our zero-sum system predicated on suffering.

Read our interview with Russell on The Antidote.

Image: Courtesy Simon & Schuster

God and Sex

by Jon Raymond

Raymond is best known for the six screenplays he’s written with director Kelly Reichardt (including Old Joy and Showing Up), many of which were adapted from his own fiction. In his latest novel, God and Sex (Simon & Schuster), a quasiacademic author who’s interested in spiritualism putters around Ashland, Oregon, falls into a love triangle, and maybe witnesses an instance of divine intervention or two. Arthur becomes fast friends with a professor while researching his latest book—a New Agey treatise on trees he hopes will be his big break—but kindles a different kind of relationship with the professor’s wife. In a plot fueled by lust (this is no fade-to-black romance), Raymond pits esoteric theologies against Old Testament catastrophe, offering a fresh, hippie-tinged valence on the timeless question of atheists and foxholes.

Read our review of God and Sex.

Blazing Eye Sees All

by Leah Sottile

Sottile, the Portland journalist and Portland Monthly contributor behind true crime hits like When the Moon Turns to Blood and the podcast Bundyville, takes on New Age wellness in her latest book, Blazing Eye Sees All (Grand Central). Past the casual tarot and crystal hobby, the question is more, “Why do we join cults?” Amy Carlson, the former McDonald’s manager turned leader of cult Love Has Won (also the title of an HBO doc on the group), is the modern example of a figure Sottile traces back to the mid-1800s: women who build rogue societies around conspiracies and, usually, claim some connection to ancient civilizations and/or the divine. There is no shortage of anecdotes about prophets turning blue after drinking so much colloidal silver. But instead of mocking, Sottile balances the absurd with the tragic. In this lineage of women, she finds a recurring attempt at agency borne from the white-knuckle grip of patriarchy.

Immaculate Conception

by Ling Ling Huang

Oregon Symphony violinist Huang made her literary debut in 2023 with Natural Beauty, a novel set at the horrific intersection of technology and cosmetic “self-improvement.” Immaculate Conception (Dutton) goes deeper, following two classmates at a hoity-toity art school through early motherhood. Their world is a techno dystopia where societal classes are segregated and made invisible to each other via obfuscating “buffers.” Technology allowing for shared—if not stolen—consciousness gives rise to a larger critique. In Huang’s book as (hopefully) in our world, art cannot be optimized for maximum profitability, even if you can take over great artists’ minds.

One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This

by Omar El Akkad

Before moving to Portland and writing two critically adored novels, American War (2017) and What Strange Paradise (2021), El Akkad spent a decade reporting internationally for Canada’s newspaper of record, The Globe and Mail. In his latest book, One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This (Knopf), which won the National Book Award, El Akkad returns to nonfiction, combining his decade of firsthand reporting with his personal experience as an Arab man to unmask America’s hypocrisies as the country becomes ever desensitized to human suffering. “El Akkad draws a bead on America’s romantic image of itself as the defiant rebel, and as a nation that holds equality as a fundamental human right,” Diana Abu-Jaber writes in a review for Portland Monthly, “while arguing the US has become the very thing it revolted against: the British Empire.”

Read Diana Abu-Jaber’s review of One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This.

Image: Courtesy Algonquin Books

Wolf Bells

by Leni Zumas

Zumas’s 2018 novel, Red Clocks, predicted the fall of Roe v. Wade. In Wolf Bells (Algonquin Books), she sets her attention on this country’s abysmal foster system and neglecting attitude toward intergenerational care. In exchange for their help caring for other residents, “youngs” live rent-free in a home for the elderly and disabled. A former punk singer runs the place, and a constant stream of jokes fly between age groups. But when a young girl and her nonverbal autistic cousin turn up on the doorstep, fleeing child protective services, the home’s accepting philosophy of no-questions refuge is put to the test. Gracefully roving between an impressive number of perspectives, Zumas uses the book’s compassionate structure to reinforce her message that empathy is too often presented as antithetical to nature.

Read our review of Wolf Bells.

Lizard Boy 2: The Most Perfect Summer Ever

by Jonathan Hill

Disguised as humans, the Lizk’t family of lizards return for a sequel to Hill’s middle grade graphic novel from 2022. In the oh so Americana suburb Eagle Valley, “the Tompkins” wear human suits and assume inconspicuous names to keep their lizard status secret. Booger Lizk’t, the family’s middle school–age son, goes by Tommy. He doesn’t like hiding himself to fit in, but finds company with a band of outsiders from school: Sasquatch, a snake girl, a robot. In The Most Perfect Summer Ever (Walker Books US), the group finds a safe space to forgo their disguises in an abandoned treehouse, a hangout and clubhouse to host long, school-free days before one of their crew, Dung, moves back to Vietnam with his family. Then an unmasked picture of Tommy/Booger turns up in the news.

Reading the Waves

by Lidia Yuknavitch

Yuknavitch’s 2011 memoir, The Chronology of Water, is a cult favorite and exemplar of the genre. A thrillingly nonlinear assemblage of vignettes, the book is a complex study of moving through trauma. Its follow-up, Reading the Waves (Riverhead Books), takes a meta approach. Revisiting many events of her first memoir, Yuknavitch investigates the ways digesting experience in literature has shaped her life—or rather, how she has shaped her life by rendering it on the page. “I’m not talking about facts,” she writes early in Reading the Waves. “I’m talking about what we do with events in our lives.”

Read our interview with Yuknavitch on Reading the Waves.

Return to Sender

by Vera Brosgol

Brosgol, a former Laika animator, made several national best-books lists with her 2024 graphic novel, Plain Jane and the Mermaid. Her latest, Return to Sender (Roaring Brook Press), marks her prose debut. It’s a middle grade adventure story: After a bout of houselessness, Oliver and his mother set out on a new life when they inherit an apartment. Oliver’s mom gets a custodial job at a private school, landing him free tuition, and his world becomes a confusing mix of wealth and poverty—more so when he stumbles upon a magical mail slot in the apartment capable of granting any wishes he scribbles in a letter. Yet soon it becomes clear that the grantings come at a cost to others. “I wish all stories were as exciting as this one,” Lemony Snicket writes in a promotional blurb.