Book Review: Douglas Lain's 'Billy Moon'

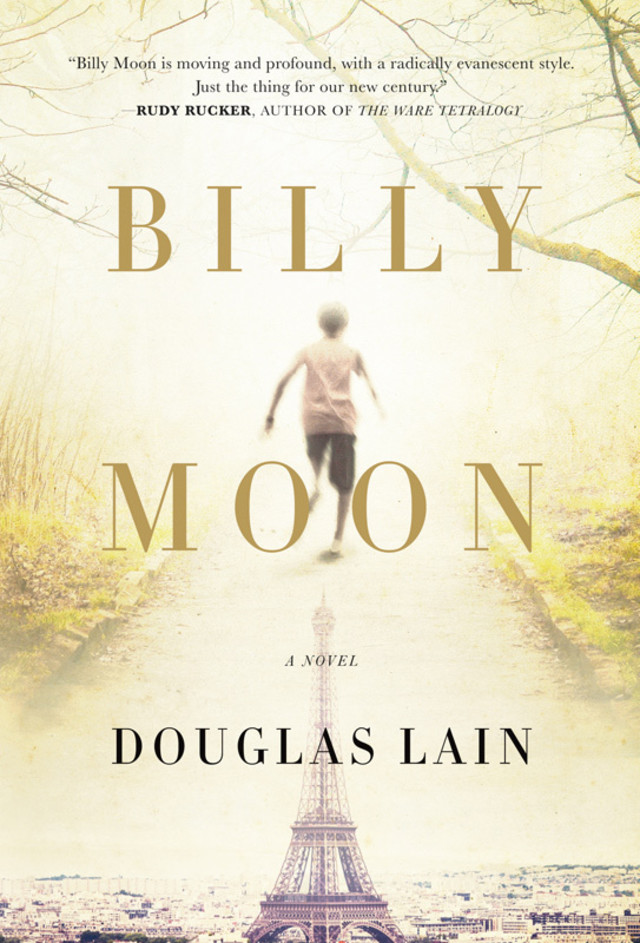

Image: Courtesy Tor Books

When you think of the Occupy movement, you probably don’t think of Paris in the ’60s, and you almost certainly do not think of Winnie-the-Pooh. But Portland writer Douglas Lain makes you do just that. His debut novel, Billy Moon, is an enchanting labyrinth of a tale that twists through surrealist reinventions of history, philosophy, nostalgia, and a search for personal liberation.

At the start of Lain’s fictitious tale, Christopher Robin Milne, the son of Winnie-the-Pooh creator A. A. Milne, is a 38-year-old World War II veteran struggling to escape the oppressive, imaginary forest that his father wrote him into. But he quickly finds his middle-aged tedium blown apart as two radical Parisians, Gerrard and Natalie, pull him into the student uprising of 1968 in Paris. Summoning Christopher from his Dartmouth, England, home, Gerrard wants him to write a new story—his own story—by disrupting Paris. “Chris was a fake person and this was how he could help,” writes Lain. “Gerrard tried to explain it to him, to tell him how the Hundred Acre Wood was waiting for him, to tell him about dreaming and how the past was inside the present.”

The nonexistent line between dreams and reality has odd effects on the narrative, as a stray cat turns into Christopher’s stuffed toy, the floor repeatedly becomes an unstable pool of mud, and Natalie stumbles upon the courtyard of the Palais-Royal transformed into a giant chessboard. Metaphor seems to saturate the endless string of impossible events, and Christopher’s slips between dream and reality reflect his attempts to escape the world of Pooh.

The history that Lain has reinvented on the page requires patience and a suspension of disbelief (about halfway through I abandoned the question “what?” altogether). But, as Christopher’s wife, Abby, remarks, “Sometimes in order to be realistic you have to accept the impossible.” Indeed, the book resonates with contemporary social movements by reviving a time where poets and philosophers raged in the streets in a revolution that critics claimed accomplished nothing.

Despite its occasional opaqueness and philosophy of the impossible, Billy Moon reaches a poignant emotional peak in Christopher’s relationship with his socially challenged young son, Daniel—a relationship that helps him cope with his estrangement from his own father. Ultimately, with its nostalgic nods to Winnie-the-Pooh and its meandering magical-realist prose, Lain’s novel offers a refreshing dose of whimsy and hope in a dull concrete world.