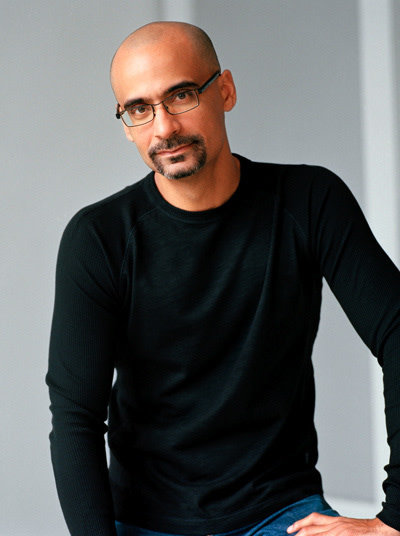

Junot Diaz: An Interview Across the Ages

Junot Diaz is a Dominican-born, Jersey-bred novelist, educator, and activist. His debut collection of stories, Drown, published in 1994 when he was just 26, won enthusiastic applause by readers and critics alike. His first novel, The Brief and Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, took another 14 years, but it won him the Pulitzer. Known to his friends as “the smart one,” and to ex-subscribers of the New Yorker as “the foul-mouthed one” (a trend that continues in this interview), Mr. Diaz returns to the public eye this month with a new story collection entitled, This Is How You Lose Her, a brief, wondrous reflection of a life marked by love, lust, and loss. Diaz will read at Powell's City of Books on Monday, October 21.

We were so inspired by Diaz’s process in Wao of incorporating hidden structures and elements that he drew from science fiction and fantasy literature that we decided to play a similar game with our interview to see if we could turn the tables. Read on for the twist.

[Ed Note: This interview was originally published on Sept. 13, 2012 in preview of Diaz's first local reading for This Is How You Lose Her, but it remains one of my favorite.]

How’re you doing today?

We have a beautiful day here in Boston, finally.

I appreciate you taking the time to do this – I know you don’t get paid extra to do phone interviews with journalists –

Aww, gimme a break, the beneficiary of this is me, so I appreciate your time.

You've spoken of your writing as “a calling.” Now, I’ve always considered novelists especially privileged in this respect, but I wonder if you think there is a possibility of being somehow disadvantaged as a novelist. Have you ever dreamt of other forms (artistic or otherwise) in which you might better express yourself? Can a calling transcend a medium?

I guess I’m lucky: my passion is strictly embedded in reading. I enjoy other mediums; I looove f**king TV, I love movies, I love comics. But it for me, in the end, I only seem to be able to do any work, any work at all, in fiction. It’s what I like the most, you know?

John Updike found the idea of teaching "truly depleting and corrupting." You’ve been at MIT for some years now—

10 years, yeah.

You seem to get a kick out of being the dusty old dude dropping some knowledge for the kids. Does it fuel your work to some extent? Do you find inspiration in it?

I don’t know if it fuels my work. Anything that takes you away from your work is, well, time away from your work. But I enjoy it as a human being. I believe in it. As a member of our civic society, I think teaching should be one of the principal professions.

My sense is that some people have a greater tolerance for being irrelevant than others and some people have a greater tolerance for working with young people than others. I find that I have a tolerance for both irrelevancy and young people that outstrips a lot my peers – and certainly outstrips Mr. Updike. But then again, John Updike was a compulsive writer, and I could imagine that preparing for a three-hour class would have taken him enough away from of his work that it would have certainly seemed to him a corruption.

There’s an affecting passage in the story, “A Cheater’s Guide to Love,” wherein our narrator, Yunior, is so driven to distraction after his big breakup that he neglects—in his civic duty as a teacher—the one minority student in his class. The reader gets the sense that the student is suffering somehow. Can you explain the motivation behind this scene?

I know this is f**ked up but, as a writer, it was just a great gag. There’s nothing more hilarious than this dumbass Yunior—even his teaching is going terribly! Even the one student that he would logically be sharing a connection with, he is not [laughs].

You find this funny! I find it a little…sad…

It should be both. I too think there is something quite terrible, quite sad in it. It’s truly remarkable how very thin the line is between tragedy and humor. And there was part of me that knew when I was organizing [this story] it should be a painful gag.

I remember working at a bookstore when Wao came out. I can tell you, if you're not aware already: an overwhelming number of Pulitzer readers are women over 40. I assume you didn't have this particular demographic in mind when writing it, but I'm sitting there reading it thinking, "there is no way anyone is going to get any of this." I'm surprised I even caught what I did. Your writing—like Joyce's wordplay, Melville's whaling arcana, Perelman's Yiddish—presupposes a great deal of knowledge on the part of your reader, reverberations that not everybody will catch. Who is your ideal reader? And does it worry you, since you often pick very contemporary subjects to write about, that your work may become outdated?

Sure. I write as a reader. I think it’s a very important distinction to write as a reader than to write as a writer. I’m always thinking about how reading works while I’m working. So I think it’s a valuable preface to say that, when I think about my ideal reader, it’s someone who still remembers what reading is. And for me, that’s someone who doesn’t need to understand everything in a book to enjoy it. When I think back, most of my reading experience was marked by an inability to understand everything that was happening on the page. Most of my reading experience had me scratching my head every now and again. There were words, there were moments…

In some way reading mirrors life—life is fundamentally unintelligible—and reading certainly has aspects to it which elude us. I guess my ideal reader is someone who is comfortable with not understanding fully what’s going on yet still able to go along for the ride. This is something that you and I do in everyday life, but when it comes to reading, we’re suddenly less likely to tolerate that unintelligibility.

Now I say that on the one hand. On the other hand: readers from New Jersey, from the Dominican Republic? If they didn’t like my work, I know my heart would break.

I'm curious about your thoughts on censorship in the New Yorker. From the late 50's all the way to the 80's, some very eminent writers capitulated to the New Yorker's unwavering stance on profanity. Part of the pleasure of reading you is that you cuss so well. When I was a kid, there was a common scenario: you went into the record store to buy the latest rap album and returned home to find that you'd accidentally purchased the "clean version." Can you imagine a clean version of your own work?

No, I always think about how many people had to suffer for me to be published the way I’m published. There’s no question. Think about it: even beyond the language, imagine how many themes were repressed… No, it’s an extraordinary moment. Sometimes we forget how much things have changed.

What does it mean to you simply as an American? I’m sure many conservatives would think we’re tossing our values out the window. Apart from allowing you to write in a particular way, is there a more significant force at work?

These conversations about values and art are always occurring in a large vacuum. And what that vacuum tells us is that there is almost no arts education. People need to fundamentally understand what the role of art is in a society—what art is. One of the dimensions of art is that it’s transgressive—and that the transgressive quality of art is very important and actually healthy for society. A society that can sustain transgressive artists is a much healthier and more democratic society than one that cannot. In fact, art trains us around certain democratic practices, so I disagree with the idea that artists are somehow emblematic of a decay in our value system. If anything, an attack on artists is emblematic of decay in our value system, you know?

I listened to a lecture you gave explaining the structure of Oscar Wao—that it contained elements of The Fantastic Four and Dune—and I was wondering, other than your new collection feeling like a bunch of breakup songs, were there any other overarching concepts for the reader to discover?

Of course. You hope that you’ve included enough dimensions to make re-reading possible. When I think about the framework for this book—the hidden structure I used to compose this book—I told myself in the beginning, this is going to be The Story of the Rise and Fall of the Cheater. This is how a cheater awakens to his responsibility and achieves the kind of human imaginary that allows him to see the women in his life as real human beings. Part of the reason we can do f**ked up shit to people is because we’re not really thinking of others as fully human—treating others as we would treat ourselves. You would never tear yourself apart the same way we casually tear people apart when we cheat. That was the simple framework, but there are other things going on in the book that I used to piece it together. It’s one of those things where you want to see how readers respond before talking about it.

I should tell you: I was so impressed with your ability to weave these structures into your work that I created my own angle to make the interview more interesting for you. Maybe I over-prepared. I took these questions from Paris Review interviews of the three most published fiction writers in the New Yorker in the year you were born: John Updike, SJ Perelman, and Donald Barthelme [Diaz was one of the three most published in 2012].

[Laughs] Wait, repeat that, what?! Oh my God. I love that. That’s a wonderful game. I adore games. That’s part of what the secret structures are inside novels: they are games—you want your readers to play along. This was a wonderful conversation across the ages, then.