Taxidermy Like You've Never Seen It Before

The world of taxidermy art is often looked at with crooked stares. Many people have a hard time with the fact that this work comes from the use of dead animals. But for many in the fringe world of modern taxidermy, the craft of repurposing the bodies of dead animals is radical: both rigorous and beautiful.

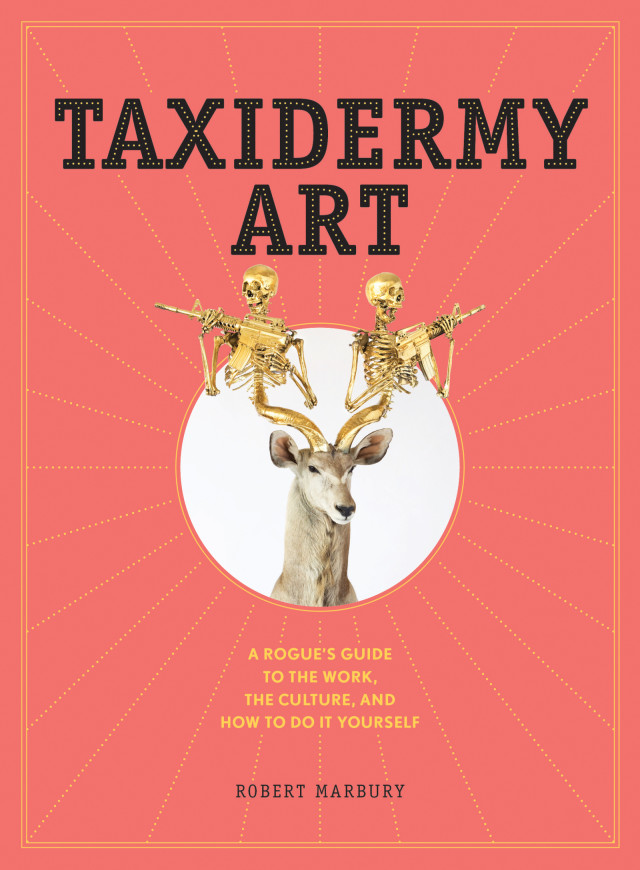

Robert Marbury, a Baltimore-based artist, decided to illuminate his world, a realm of art he refers to as "rogue taxidermy," in his new book Taxidermy Art: A Rogue's Guide To the Work, the Culture, and How to Do It Yourself.

Marbury's foray into taxidermy began in late-90s New York City through an obsession with naturalism, cryptids, and stuffed animals. "I like this idea of taking trash and using it, and I like this idea of feral nature; of an unidentified animal living in an urban environment," Marbury told PoMo.

He began collecting stuffed animals and creating taxidermy versions of them, adding real jaws and glass eyes. Then he would leave them in parks around New York City. The idea was to take these imaginary wild animals and displace them in the urban wild.

Robert Marbury

Paxton Gate

Oct 13Quickly this passion project turned into a full-time gig for Marbury, as he began traveling the world, meeting innovative taxidermists, and cataloging their stories. His book is carefully curated and yet utterly diverse—a work of history, exhibition, and tutorial—so we asked Marbury to highlight his six favorite pieces and explain what is special about them and the artist behind them. We begin with the Portland artist among the bunch, whose work graces the book's cover.

Peter Gronquist, Untitled

Peter Gronquist, Untitled, from Taxidermy Art by Robert Marbury (Artisan Books). Copyright © 2014. Photo: Jeremiah Alley.

I like how Peter Gronquist plays with consumer dichotomies, using the visual language of sport, trophy, and prize in the same context of both game-hunting and luxury-good buying. On my trip to Portland last August, I spent the day riding around with Peter Gronquist. It was a bit like those cop documentaries, where the journalist is embedded with a squad car: all kinds of stuff happens and the journalist is accidentally shot in the leg, which changes his life forever.

Not only did I thoroughly enjoy talking with Peter about his process, but I loved his style. The biggest compliment I can give him is that after meeting Peter in Amsterdam, my wife said, "it is too bad you don't live closer to Peter, because you could get into a lot of trouble together."

Rod McRae, Crying Out Loud In The Age Of Stupid

Rod McRae, Crying Out Loud In The Age Of Stupid, from Taxidermy Art by Robert Marbury (Artisan Books). Copyright © 2014. Photo: Robert Marbury.

Rod’s main focus is pulling people into the dialogue that things are not right. In his other life, he’s a children’s book illustrator. I think some of his work explains that. There’s this amazing disconnect where children, especially, have such access to the concept of animals but not the reality of animals. Rod plays with that.

The bear on a refrigerator has so many narratives to it. It could be seen as a pun, like a New Yorker cartoon made from flesh. It’s pointed and funny. It gives you an opinion right away and it sticks with you. But at the same time it allows the individual to come to the table the way that is comfortable for them. Conservationists are always battling with that, with how to get people to the table. Humor is very sticky, it’s very tacky, and it allows you to come to the table and stay at the table. I think he does a really beautiful job of that.

Les Deux Garçon, L'Adieu Impossible

Les Deux Garçon, L'Adieu Impossible, from Taxidermy Art by Robert Marbury (Artisan Books). Copyright © 2014. Photo: Robert Marbury.

Their work is some of my favorite. I love the way they create this story. They bring you into this other realm of existence. These Siamese pieces are just so beautiful.

They work with a fourth generation taxidermy family in the Netherlands. Their work is a lot about collecting and finding the right piece and putting the right piece together the right way. Their ribbons and the way they accentuate the pieces—I really believe it not only takes you into this prehistorical place but that concept of saudade, a Portuguese term that describes this idea of longing. It gives you this feel of longing for an age that you’ve never experienced but believe existed.

Jessica Joslin, Aria & Sola

Jessica Joslin, Aria & Sola, from Taxidermy Art by Robert Marbury (Artisan Books). Copyright © 2014. Photo: Robert Marbury.

I like to think of Jessica as a tinker. If it’s not clear, she does, I think she was calling it, “Osteology.” She’s not doing taxidermy. Taxidermy is only arranging skin. I expanded the definition pretty liberally to artists that were doing animal work or bio-art and using taxidermy materials or taxidermy theory. She’s really doing bone work.

There’s this Chicago cop bringing her empty shells from guns, so she uses those and bends them and turns them. What I love is that she’s disguising these utilitarian pieces into preciousness. It’s almost alchemy: she’s taking something that’s ordinary and making it very special.

Julia deVille, Orcus

Julia deVille, Orcus, from Taxidermy Art by Robert Marbury (Artisan Books). Copyright © 2014. Photo: Robert Marbury.

Julia is vegan. She is adamantly against industrialized farming. Her work has a very elegant quality. She is a jeweler, so her business is jewelry, and jewelry that fits into the memento mori genre. She’s very conscious of the limits of life. She’s actually donated her body to get plastinated.

The pig piece has the quality of the gilded Victorian death portrait. In the Victorian period there was this thing where you would dress stillborns up and make these ornate settings and photograph the dead babies. It’s pretty rough. In some ways she’s doing that. She’s taking these “children,” which happen to be animals who went through industrialized farming, and she’s giving them this second memorial. Pigs don’t always get that.

Scott Bibus, Swan Song

Scott Bibus, Swan Song, from Taxidermy Art by Robert Marbury (Artisan Books). Copyright © 2014. Photo: Robert Marbury.

Scott is traditionally trained, and what he noticed is that in traditional taxidermy, there was no death in death. It was always showing life in death. I think partially due to horror movies and video games and death metal, his humor is definitely aligned with flipping the narrative into the horror genre.

Nature’s not kind. You see animals doing unkind things all the time, but humans like to believe that animals are kind and above reproach. I think Scott takes those two things and plays with the fact that there is death in nature, but it also has this humor of throwing you in the deep end in terms of what you’re looking at.

If you talk to him, he can artistically and philosophically walk you around his work. He’s able to place it in terms of anatomical models and the way gore was represented during the Victorian era.

He has this great shock value that makes you step back and maybe reconsider.