What Would Chekhov Really Think of Twitter?

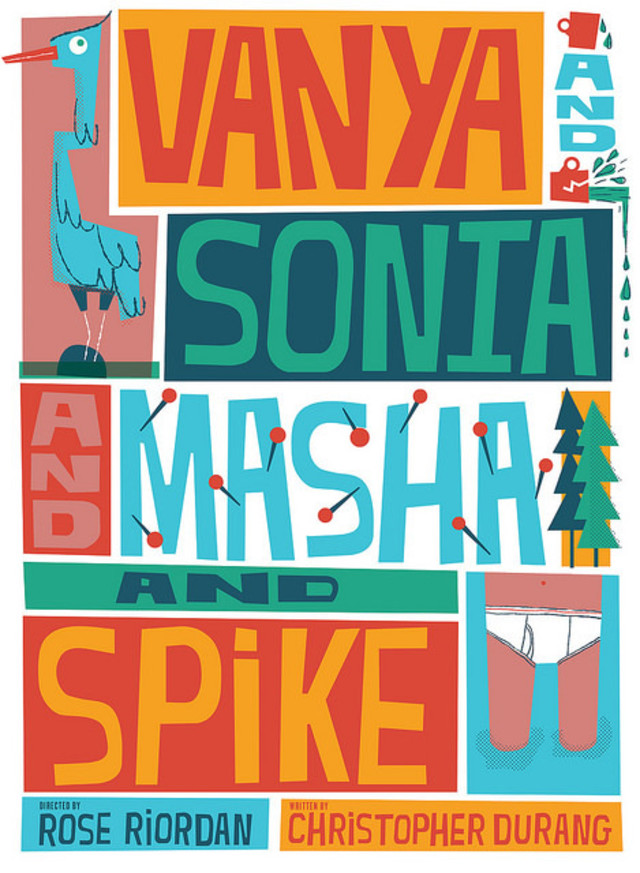

As a millennial, I’m not sure I’m the intended audience for Christopher Durang’s 2013 Tony-winning comedy Vanya and Sonia and Masha and Spike, running this month at Portland Center Stage. (Take, for example, a climactic scene that centers around a hermetic Luddite’s impassioned rant against changing times, triggered by impolite texting.)

So who exactly is the audience for this, the most-produced play of 2014? Well, certainly fans of Anton Chekhov, the melancholic Russian master who inspired Durang's script. Vanya et al. mashes up Chekovian characters, plots (especially Uncle Vanya and The Seagull) and themes—depression, narcissism, existential angst that life has passed you by—with distinctly postmodern angst. Results are, as one might expect, mixed.

Vanya and Sonia, two middle-aged malcontents who rarely leave the house they grew up in, get a visit from their self-absorbed movie star sister Masha and her much younger boy toy, Spike. Masha’s glamorous career supports her two siblings—things are tense. A comedy based largely on opposing personalities demands strong performances, and the PCS cast uniformly delivers.

Sharonlee McLean is a delightful bundle of neuroses and self-effacement as Sonia, and Carol Halstead embodies the attention-starved minor celebrity as Masha—something like 30 Rock’s Jenna Maroney, a decade or so older and with even less self-awareness. Andrew Sellon’s Vanya is a study in control, all placid and resigned acceptance until he bursts near the end.

Image: Portland Center Stage

Yes, Vanya’s rant. It is, in many ways, the play’s most touching moment, an eloquent (if crazed) eulogy for bygone days of hand-written letters and common cultural touchstones like the Ed Sullivan Show, and a striking image of a vulnerable man releasing his pent up fear of the fast changing world around him.

There’s a lot of room for nuance there, but the scene feels half-baked. Vanya’s complaint, for example, that “there are no more shared experiences, there’s just Twitter,” comes off as overwrought whining, oblivious to the app’s appeal as a medium for, yes, shared experiences.

Image: Portland Center Stage

Maybe Durang is intentionally mocking techphobic ignorance. But in a play where the only two young characters are an effusively naive teenager and a talentless, dim-witted hunk, it’s hard to say how well that sort of nuance translates.

We’re talking about a nearly sexagenarian man who rarely leaves his house complaining about how TV was better when he was younger, and yet the rant feels like less of a tragicomic climax and more like a triumphant moment for a character who’s become the moral center of the play; the overwhelmingly middle-aged theatergoers around me cheered loudly when Vanya’s tirade ended. And as part of a script that’s essentially one big in-joke about Chekhov, it was hard to shake the feeling that I was watching theater folk fret about a modern world in which their craft is losing cultural traction (which, of course, would explain why Tony voters found the play so appealing).

But if you don’t leave your house much—or your insular community, for that matter—that’s what you might not realize about the fast-paced, postmodern cultural landscape for which Twitter may or may not be a symbol: with so many options out there, fighting for the good things makes them so much more worthwhile.